What's Cookin'? Earth, Basically. But It's Not El Niño's Fault

It's getting hot in here; global average temperatures last year broke records, with 2015 steaming into first place as Earth's hottest year since record keeping began in 1880. Scientists have analyzed the balmy trend, and El Niño is just part of the story, they say.

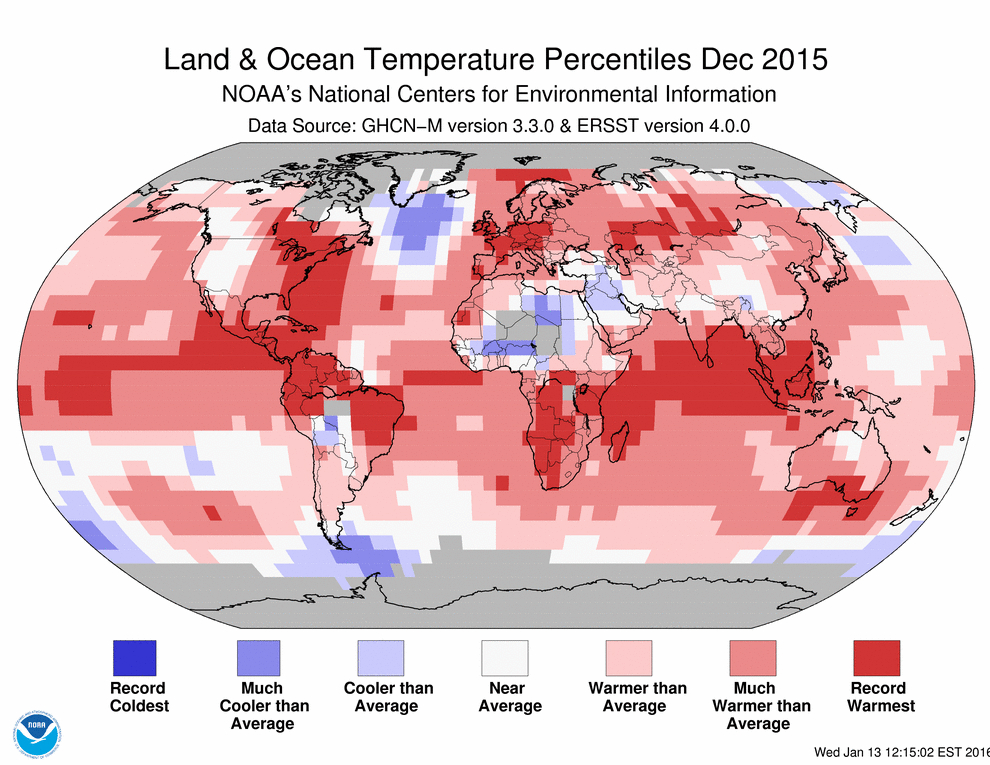

Temperatures for December 2015 were especially unusual, with the highest average temperatures on land and sea surface recorded for any single month during 136 years of record keeping, according to a Jan. 20 statement by NASA and a report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Part of the explanation for the heat spike toward the year's end lies in 2015's strong El Niño, a cyclical event that moves warm water along the equatorial Pacific from west to east, triggering climate activity that can drive temperatures upward in parts of the world and contribute to some extreme weather episodes. But El Niño alone wasn't responsible for the high temperatures that prevailed throughout the year, according to Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"Last year's temperatures had an assist from El Niño," Schmidt said in the statement, "but it is the cumulative effect of the long-term trend that has resulted in the record warming that we are seeing." [Watch Earth Get Hotter — 135 Years of Temperature Changes Visualized]

Global climate data analyzed independently by NASA and NOAA, and presented today, told the same story, and a familiar one: 2014, formerly the warmest year on record, lost its title once 2015 wound to a close, clocking in at 0.23 degrees Fahrenheit (0.13 degrees Celsius) warmer than its predecessor, according to the statement. This is only the second time in 136 years that a previous temperature record has been broken by such a wide margin.

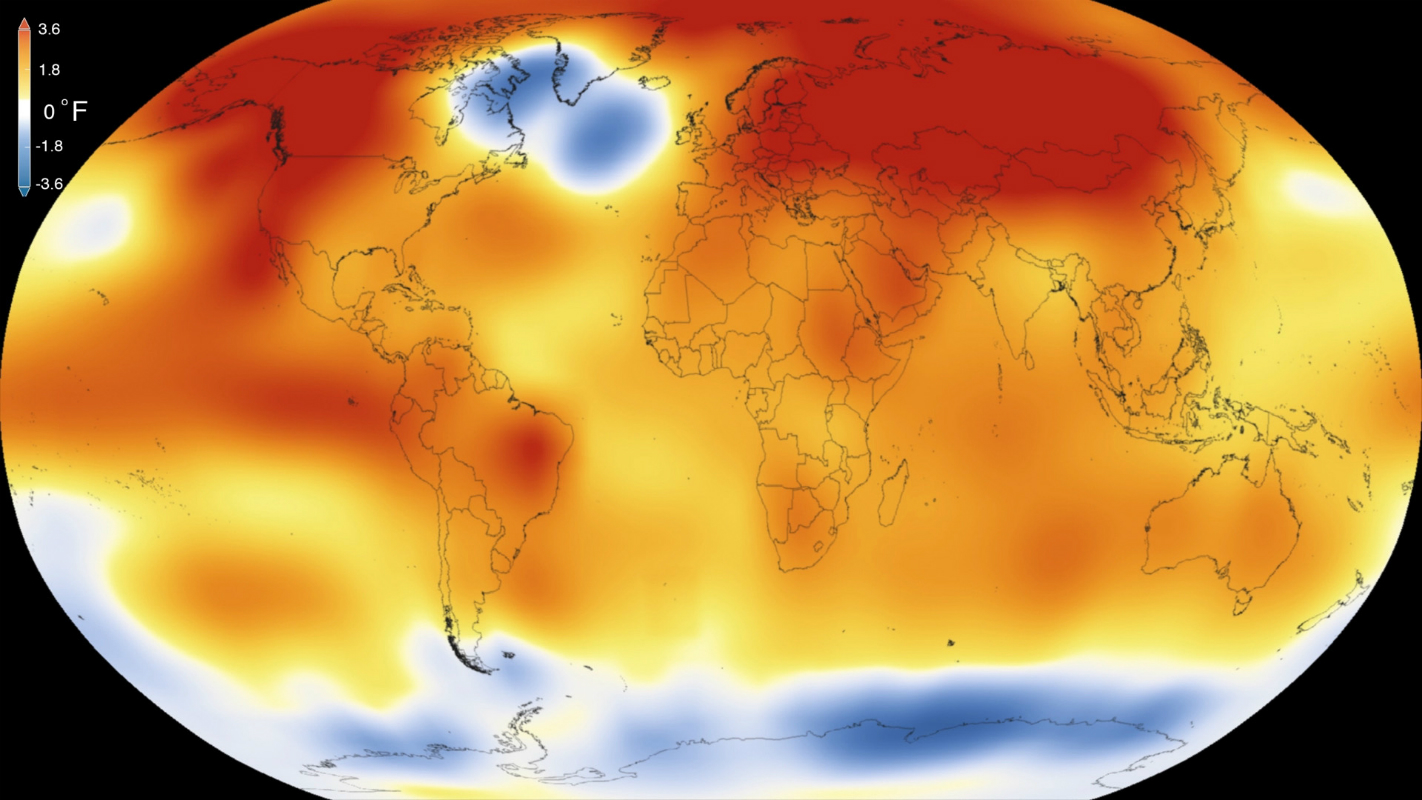

And 2015 is only the latest benchmark in a warming trend that spans over 100 years, according to NASA. In the statement, officials pointed to increasing atmospheric levels of human-made emissions like carbon dioxide that drive global temperatures upward, increasing Earth's average surface temperature by 1.8 degrees F (1 degree C) since the end of the 19th century.

But to what extent was El Niño responsible for a warmer-than-average 2015? From year to year, Earth's oceans and atmosphere engage in a complex dance that moves heat and moisture around the planet. Their movements follow patterns, which become visible over decades of observations. One of those recurring patterns is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), responsible for El Niño and its counterpart, La Niña.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

El Niño develops about once every five years, according to Steven Pawson, an Earth scientist and chief of the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. To track El Niño, experts look to an equatorial central Pacific zone known as the Niño 3.4 region. Warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in this zone, calculated over months, tell scientists that El Niño conditions are active, Pawson told Live Science. When sea surface temperatures there are exceptionally warm, "that's a strong El Niño," Pawson said.

And during 2015, a strong El Niño developed, carrying warmer waters from the tropical Pacific east toward South and Central America. The warm waters engage with atmospheric circulation, generally bringing more rain to Southern California and the Gulf Coast — which we saw in 2015, Pawson said. But while El Niño delivered badly needed moisture to the U.S.'s West Coast and southern states, it brought drier than usual conditions to the Amazon, leaving it susceptible to fires toward the middle of 2016, Pawson added. [How El Niño Causes Wild Weather All Over the Globe (Infographic)]

Warmer winter temperatures in the eastern United States are also a hallmark of El Niño. "Typically, El Niño does give us a warmer-than-normal East Coast, especially in the early part of the winter," Pawson said, adding that El Niño was still likely not entirely responsible for 2015's unusually balmy winter temperatures.

And El Niño's effects weren't felt until later in 2015 anyway, Schmidt explained during the NASA/NOAA press conference. Global temperatures generally respond to a developing El Niño after four to six months, he said, while 2015's warming trend was evident from the very beginning of the year.

However, Schmidt pointed out that the last few months of 2015, with temperatures that were abnormally warm, were reacting to the current El Niño. And 2016, which is kicking off with a strong El Niño already in progress, is expected to be an exceptionally warm year, perhaps another record setter, he added.

The evidence glimpsed in warming trends over time shows that other factors are pushing global temperatures steadily higher as the years go by, Schmidt said, warning that "this will be continuing and accelerating" with increased burning of fossil fuels and carbon dioxide emissions.

And there are consequences that come with warming. Heat waves, sea-level increases and glacier loss, Schmidt said, which we are already seeing now, are directly related to global warming. And scientists expect events like these to continue into 2016 and onward, as warming continues.

It's less clear if a warming world means stronger El Niño events that would bring more extreme weather and even greater temperature anomalies to the globe, Pawson told Live Science; that's largely because El Niño occurs only about 20 times in 100 years, so it's harder to detect long-term trends that develop over time.

"There's climate change happening. There are El Niños happening, with varying strengths. And time's going to tell if the character of El Niño is changing because of climate change," Pawson said.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus