Antarctic Science Lab On the Move to Escape Breaking Ice

A British scientific base in Antarctica is on the move to a new location, to avoid being cut adrift by a crack in a floating ice shelf.

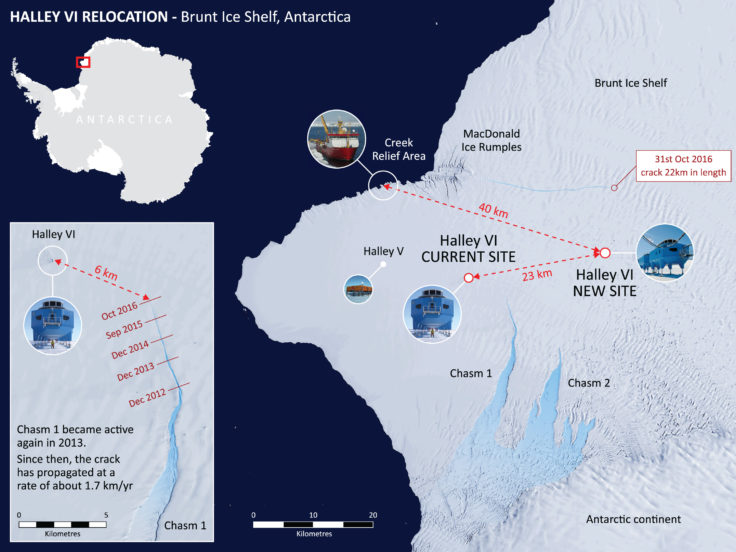

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) announced on New Year's Eve that the first module of the Halley VI Research Station was towed by tractors to a new site on the Brunt Ice Shelf in Antarctica's Weddell Sea, 14 miles (23 kilometers) east of its former location.

The remaining seven main buildings of the modular research base will be towed to the new site over the coming weeks, as the relocation team takes advantage of the 24 hours of daylight during the brief Antarctic summer. [See Photos of the Antarctic Research Base Being Moved]

"It's been a very positive couple of days for the team," BAS officials posted on the organization's Facebook page on Dec. 31. "Last night they managed to successfully tow the first of the eight Halley modules to the new site at Halley 6a."

The modern Halley base is the sixth British research station of that name built on the floating Brunt Ice Shelf since 1956. Each of its main modules is equipped with hydraulic legs and skis, but this is the first time they have been moved since the new base became operational in 2012.

The Brunt Ice Shelf is typically around 490 feet (150 meters) thick. But scientists have learned that a long-dormant chasm in the ice southeast of the base is now growing by more than 1 mile (1.7 kilometers) each year, and threatens to eventually cut the base off from the inland section of the ice shelf.

Surveys of the ice shelf have located a new site for the base, inland of the chasm, and preparations to move the base buildings began last year, according to the BAS.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On the move

Now that the relocation of the Halley base is underway, BAS staff have only a few weeks left of polar summer to complete the move.

"Each summer season is very short — about nine weeks," BAS operations director Tim Stockings said in a statement. "And because the ice and the weather are unpredictable, we have to be flexible in our approach."

"We are especially keen to minimize the disruption to the science programs. We have planned the move in stages — the science infrastructure that captures environmental data will remain in place while the station's modules move," Stockings said.

The BAS hopes to have the Halley VI base fully operational at the new site by the 2017/2018 Antarctic summer, when the environmental programs will also be relocated.

BAS communications manager Athena Dinar said it would take up to 15 hours for specialized tractors to tow each of the eight Halley modules over the 14 miles (23 kilometers) to the new site. "It will be taken very slowly as the [operational] modules have not been towed before," she told Live Science.

The eight main Halley modules provide accommodation and research facilities for around 60 British scientists and support staff during the Antarctic summer months, Dinar said. Over the winter months, a few staff members keep the base operational and the experiments running.

Watching the skies

Britain's Halley base has played an important role in studies of the Earth's atmosphere. Weather and atmospheric data, including measurements of ozone in the Earth's upper atmosphere, have been collected since the first base, Halley I, was established in 1956, according to the BAS.

In 1985, scientists at Halley VI discovered Antarctica's "ozone hole" — a region of ozone-depleted air in the upper atmosphere over the continent that worsens during the south-polar spring.

Subsequent research linked the Antarctic ozone hole to the accumulation in the Earth’s upper atmosphere of chlorine-based chemicals, such as the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) once used as refrigerants and in aerosol cans. The discovery led to the development of the Montreal Protocol, a global effort adopted in 1987 to eliminate the use of CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals.

As well as continuing measurements of the ozone layer and other physical processes in the atmosphere, current research programs at Halley VI include taking advantage of the base's location near the South Pole to monitor interactions between the solar wind and the Earth's magnetic fields, which can trigger frequent displays of the aurora australis, or southern lights.

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus