500-Year-Old Hidden Images Revealed in Mexican 'Manuscript'

Storytelling images on a deer-hide "manuscript" from Mexico have been seen for the first time in 500 years, thanks to sophisticated scanning technology that penetrated layers of chalk and plaster.

This "codex," a type of book-like text, originated in the part of Mexico that is now Oaxaca, and is one of only 20 surviving codices that were made in the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans.

The codex's rigid deerskin pages were painted white and appeared blank, but those seemingly empty pages came to reveal dozens of colorful figures arranged in storytelling scenes, which were described in a recently published study. [10 Biggest Historical Mysteries That Will Probably Never Be Solved]

Known as the Codex Selden, the mysterious book dates to about 1560. Other Mexican codices recovered from this period contained colorful pictographs — images that represent words or phrases — which have been translated as descriptions of alliances, wars, rituals and genealogies, according to the study authors.

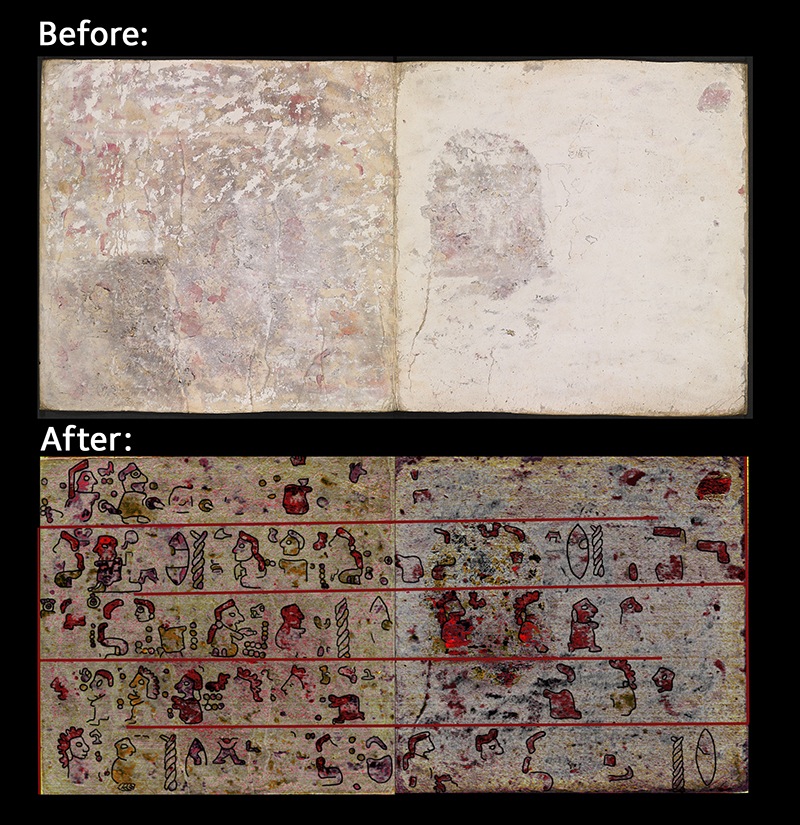

But Codex Selden was blank — or so it seemed. Made from a strip of deerskin measuring about 16 feet (5 meters) long, the hide was folded accordion-style into pages, which were layered with a white paint mixture known as gesso. In the 1950s, experts suspected that there might be more to this codex than its empty pages suggested, when cracks in the gesso revealed tantalizing glimpses of colorful images lurking underneath the chalky outer layer, which was likely added so that the book could be reused.

In the years that followed, scientists carefully removed some of the gesso in several areas of the codex, but the images were still mostly obscured. Infrared imaging provided general shapes of the pictographs under the gesso, but not much detail. And X-ray scanning — commonly used with art objects or historical artifacts to explore unseen layers — failed to reveal these hidden pictures because they were created with organic paints and don't absorb X-rays.

But a newer technique called hyperspectral imaging was able to penetrate the layers of gesso by collecting information from all frequencies and wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum. The researchers were finally able to view the underlying images without damaging the pages, and discovered a collection of images, inked in red, yellow and orange. [Image Gallery: Ancient Texts Go Online]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

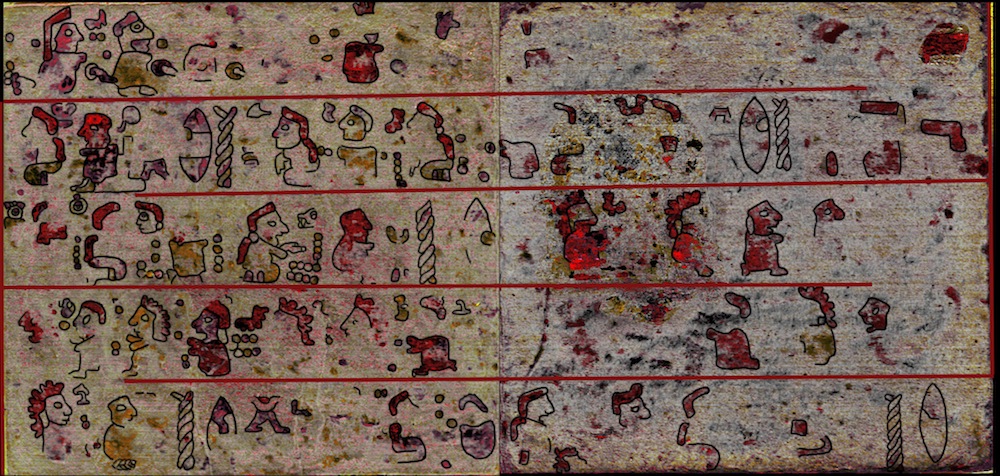

They analyzed seven pages of the codex, describing parades of figures that represented men and women, with 27 people on one page of the codex alone. The figures were seated and standing. Two figures were identified as siblings, as they were connected by a red umbilical cord. Some of the figures were walking with sticks or spears, and several of the women had red hair or headdresses.

The researchers also recognized a recurring combination of glyphs — a flint or knife and a twisted cord — as a personal name. That name, they said, might belong to a character who appears in other codices — an important ancestral figure in two known lineages. However, further investigation would be required before they could confirm whether this is the same person, the study authors said, and novel imaging technology will likely play an important role in filling in the missing pieces of this centuries-old puzzle.

Hyperspectral imaging showed "great promise" for this reconstruction of the hidden codex, according to David Howell, study co-author and head of heritage science at the Bodleian Libraries, where the codex is housed.

"This is very much a new technique," Howell said in a statement. "We've learned valuable lessons about how to use hyperspectral imaging in the future both for this very fragile manuscript and for countless others like it."

The findings were published online in the October 2016 issue of Journal of Archaeology: Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus