Jewish Escape Tunnel Uncovered at Nazi Massacre Site

A 115-foot-long escape tunnel hand-dug by Jewish prisoners has been discovered at a Nazi execution site in Lithuania, a team of archaeologists and geoscientists announced today.

It's been estimated that up to 100,000 people —most of them Lithuanian and Polish Jews —were massacred at the infamous killing site in the Ponar forest, just outside the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius, between 1941 and 1944.

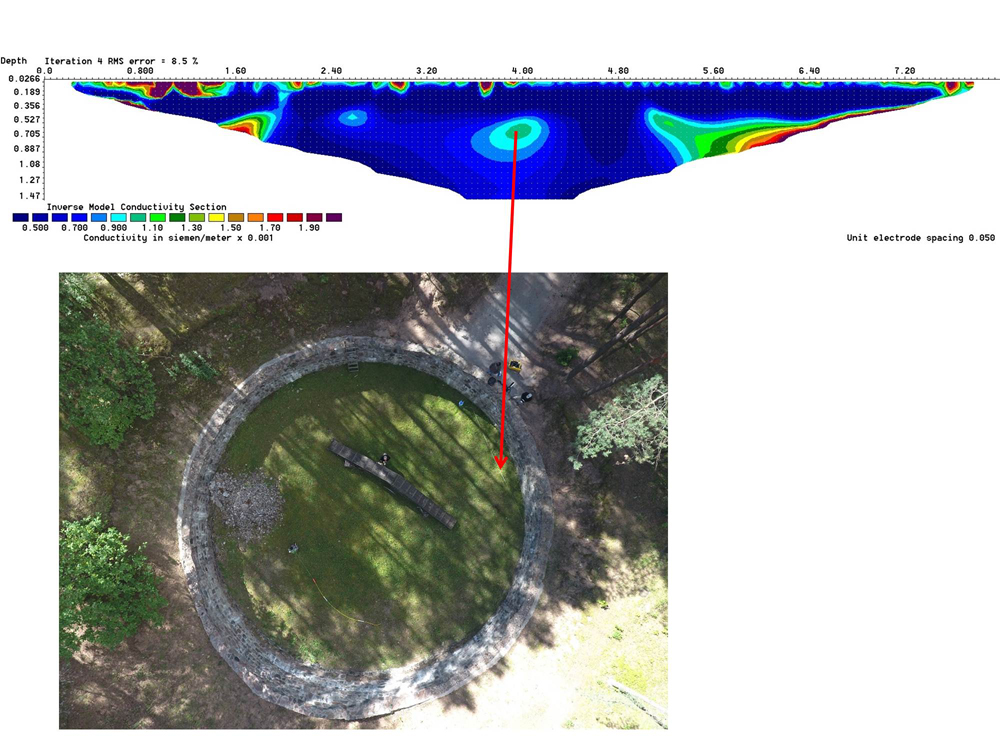

Using a remote-sensing technique, a group of researchers was able to relocate the narrow tunnel at Ponar without ever breaking ground. [See Photos of the Jewish Escape Tunnel at Ponar]

Spoon-dug tunnel

German forces took control of Vilnius in the summer of 1941. Soon afterward, the military established Jewish ghettos in the city and began periodic killings at Ponar. In the three years that followed, 95 percent of Lithuanian Jews were killed.

By 1943, Soviet forces were closing in on the region, and the German military formed a special unit of 80 Jewish prisoners from the Stutthof concentration camp who were tasked with covering up the evidence of genocide at Ponar, the researchers said. Known as the "burning brigade," these prisoners were kept in a former execution pit at night, and forced to open the mass graves and burn the corpses during the day.

Some members of the unit plotted an escape, and over the course of three months they dug a tunnel about 115 feet (35 meters) long, using spoons and their hands. On April 15, 1944, the last night of Passover that year, about 40 of the prisoners attempted to escape through the tunnel. Many were caught and shot by their Nazi guards, the researchers said. Only 11 reached the Jewish resistance forces and survived the war; the survivors gave testimonies about what happened at Ponar.

Looking underground

Researchers from Israel, Lithuania, the United States and Canada recently set out to find the exact location of the lost tunnel. The team used a technique called electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), which detects changes in electrical properties underground. Often used in the oil and gas industry, ERT can help find buried archaeological features. (For example, limestone foundation blocks and porous soil could be distinguished by their different levels of electrical resistivity, the reciprocal of conductivity.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only the entrance of the tunnel (from inside the prisoners' pit) had been known, but earlier this month, the researchers detected the rest of the passage. The team also detected previously unknown mass grave pits in the surrounding forest, which could hold more Ponar victims.

"As an Israeli whose family originated in Lithuania, I was reduced to tears on the discovery of the escape tunnel at Ponar," Jon Seligman, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority who worked on the project, said in a statement. "The exposure of the tunnel enables us to present, not only the horrors of the Holocaust, but also the yearning for life."

Uncovering Holocaust accounts

In recent years, archaeologists have used their skills to uncover evidence of atrocities at several other World War II sites. For example, the first excavations at the Treblinka death camp a few years ago revealed new mass graves and the first physical proof of gas chambers at the site.

"Geoscience will allow testimonies of survivors — like the account of the escape through the tunnel — and many events of the Holocaust to be researched and understood in new ways for generations to come," another investigator on the project, Richard Freund, a professor of Jewish history at the University of Hartford in Connecticut, said in the statement.

The findings at Ponar will be documented in a film set to air on the PBS science series NOVA in 2017.

Original article on Live Science.