Gospel of Jesus's Wife Likely a Fake, Bizarre Backstory Suggests

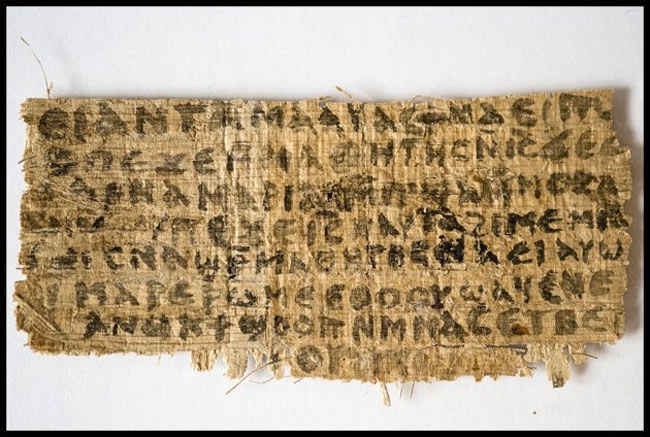

A papyrus holding text that suggests Jesus Christ was married and whose authenticity has been a matter of intense debate since it was unveiled in 2012 is almost certainly a fake.

Karen King, the Harvard professor who discovered the Gospel of Jesus's Wife and has defended its authenticity, has now conceded that the papyrus is likely a forgery and that its owner lied to her about the provenance and his own background.

The concession comes after Walter Fritz, a resident of North Port, Florida, revealed that he is the owner of the papyrus that claims Jesus had a wife. Fritz said this to Ariel Sabar, a journalist for The Atlantic who wrote an exposé published June 15.

Less than a day after that article was published, more documents came out revealing a fake Greek manuscript the owner had posted on his website and a blog in which the owner’s wife talks of restoring a second century Christian gospel, a project that apparently left part of the manuscript in fragments.

Then on the evening of June 16, King conceded that the papyrus is likely a forgery. The new evidence "tips the balance toward forgery," King told Sabar. [6 Archaeological Forgeries That Could Have Changed History]

The Gospel of Jesus's Wife contains the words "Jesus said to them, 'My wife...,'" suggesting that some people, in ancient times, believed that Jesus had a wife. King announced its discovery in September 2012.

A number of scholars suspected that Fritz was the owner; Live Science's prior investigations also revealed that he might have been the owner. With Fritz's ownership confirmed, new documents related to the Gospel of Jesus's Wife were published on the blog of Christian Askeland, a research associate with the Institute for Septuagint and Biblical Research in Wuppertal, Germany.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Additionally, Live Science had obtained several documents that were being withheld until Fritz was confirmed as the owner of the papyrus. These documents can now be published.

Authenticity debate

The papyrus received extensive media coverage after it was first revealed in 2012. Scientific tests published in April 2014 in the journal Harvard Theological Review supported the authenticity of the papyrus. However, another series of studies published in the journal New Testament Studies in July 2015 suggested it was a forgery, having been copied, in part, from an online translation of the Gospel of Thomas published in 2002.

Fritz claims to have purchased the Gospel of Jesus's Wife, along with other papyri, in 1999 from a man named Hans-Ulrich Laukamp, the owner of ACMB-American Corporation for Milling and Boreworks in Venice, Florida. The two men worked together at the company, with Fritz becoming president of its U.S. operations.

In 2014, Live Science interviewed Laukamp's stepson, René Ernest, who said that Laukamp did not own the papyrus and had no interest in antiquities. Axel Herzsprung, a friend and business partner of Laukamp, also told Live Science that Laukamp did not collect papyri.

Sabar, of The Atlantic, also interviewed Ernest and Herzsprung for his article. Again, the two denied Fritz's claims, saying that Laukamp did not own the papyrus. Ernest told Sabar that Laukamp was a kind-hearted individual with minimal education who drank a lot and had no interest in antiquities.

Herzsprung described Fritz as a smooth talker who suckered Laukamp into giving him an executive position at ACMB. Fritz "was very eloquent," Herzsprung told Sabar, adding that "Laukamp was easily influenced — he didn't have a very high IQ — and Fritz was successful in talking his way in."

"Herzsprung made no effort to hide his hatred of Fritz," Sabar wrote. "I was so angry at him that I thought it was better we never meet in the dark somewhere," Herzsprung told Sabar.

Nefer Art

In 1995, Fritz founded a company called Nefer Art. (The word nefer is an Egyptian word for beauty; the company offered an array of services to art collectors.) "Our customer database is substantial, and our discreet and confidential services are perfect for the distinguished collector and seller who likes to avoid the pushy atmosphere of the big auctions [sic] houses," an old page of the company's website read.

Another page (which can still be seen) from the company website shows an array of artifacts, including a Greek text that multiple scholars identified as a fake when asked by Live Science. There is also an Arabic manuscript that is shown horizontally inverted. The Arabic manuscript has reddish spots on it; what they are is unknown, however, "orange spots" were found on the back of the Gospel of Jesus's Wife during an examination, King wrote in an article published in 2014 in the journal Harvard Theological Review. Whether the spots on the Arabic text have any relation to the spots on the Gospel of Jesus's Wife is unknown. The Arabic text has been unpublished until now.

The Greek text (seen here) is a terrible forgery, Askeland wrote on his blog. The text is written in a script "appropriate to a modern printed edition," he wrote, noting that "the cut along the left-hand side resembles one on the GJW [Gospel of Jesus's Wife]."

Anitra Williams-Fritz

Fritz is married to Anitra Williams-Fritz, an author who recently published a book of "automatic writing," which, as described in the book's summary, "involves allowing the spirit or higher self to simply flow through, to create, or guide the words that she writes. These writings are a very effective way for her to channel, as the message comes directly to her hand from her higher being and others."

Askeland found a web page suggesting that Williams-Fritz was also involved with papyri. She ran a business called Cute Art World, which, on Aug. 31, 2009 — just a few months before her husband Fritz contacted King (of Harvard) for the first time — advertised pendants showing illustrations of the Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus. Images on the pendants contained a tiny scrap of papyri.

Williams-Fritz said the fragments are from a restoration project that involved a Coptic Christian gospel. [Religious Mysteries: 8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

"These fragments are really old and come from a larger Christian papyrus, dating back to the 2nd Century A.D," Williams-Fritz wrote in the descriptions of the pendants. "The larger papyrus was probably part of a gospel or an early Christian text, written in the Sahidic Coptic language. The fragments were left over and couldn't be incorporated into the big papyrus any more because they were so small."

A fake letter

Fritz provided King with a contract he signed with Laukamp, as well as a typed letter, supposedly from 1982, saying that Peter Munro, a professor at the Free University of Berlin, and colleagues had examined Laukamp's papyrus.

Sabar got a copy of this letter from Fritz and obtained copies of Munro's archived correspondence comparing the two. Sabar concluded that the letter was a fake.

"The problems were endemic. A word that should have been typed with a special German character — a so-called sharp S, which Munro used in typewritten correspondence throughout the '80s and early '90s — was instead rendered with two ordinary S's, a sign that the letter may have been composed on a non-German typewriter or after Germany's 1996 spelling reform, or both," Sabar wrote.

"In fact, all the available evidence suggests that the 1982 letter isn't from the 1980s," Sabar continued. "Its Courier typeface does not appear in the other Munro correspondence I gathered until the early '90s — Fritz's final years at the [Free University of Berlin]. The same is true of the letterhead. The school's Egyptology institute began using it only around April 1990."

Egyptology background

Sabar found that Fritz started studying for a master's degree in 1988 at the Free University of Berlin, before dropping out a few years later. Before he dropped out, Fritz published an article in German in 1991 in the journal Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. The paper detailed a study of the Amarna tablets, diplomatic correspondence between the pharaoh Akhenaten and other ancient leaders. Fritz also has a technical degree in architecture, Sabar found.

While Fritz denied forging the Gospel of Jesus's Wife, he admitted that he had the capability to do so. "Well, to a certain degree, probably," Fritz told Sabar. "But to a degree that it is absolutely undetectable to the newest scientific methods, I don't know."

Although Fritz was willing to talk to Sabar and disclose his ownership, he was unwilling to talk to Live Science. When we called him in April 2014, Fritz denied being the owner of the papyrus or knowing Laukamp. Fritz and his wife refused to communicate further with Live Science.

Porn business

Sabar also revealed that Fritz had started a pornography business in 2003. "Beginning in 2003, Fritz had launched a series of pornographic sites that showcased his wife having sex with other men — often more than one at a time," Sabar wrote.

Apparently, according to Sabar, the couple would advertise free "gangbangs," asking interested men to email "Walt" so they could be cleared to attend.

Though these sites seem to have been taken down between 2014 and 2015, archived images and video still exist online, Sabar found.

"He lied to me"

King has conceded that Fritz lied to her about the provenance of the papyrus but said she cannot be certain yet that the papyrus itself is a fraud.

"King said she would need scientific proof — or a confession — to make a definitive finding of forgery," Sabar wrote. However, King added that the evidence now "presses in the direction of forgery."

"I had no idea about this guy [Walter Fritz], obviously," King told Sabar. "He lied to me."

This article was originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus