This Negative Facial Expression Is 'Universal'

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

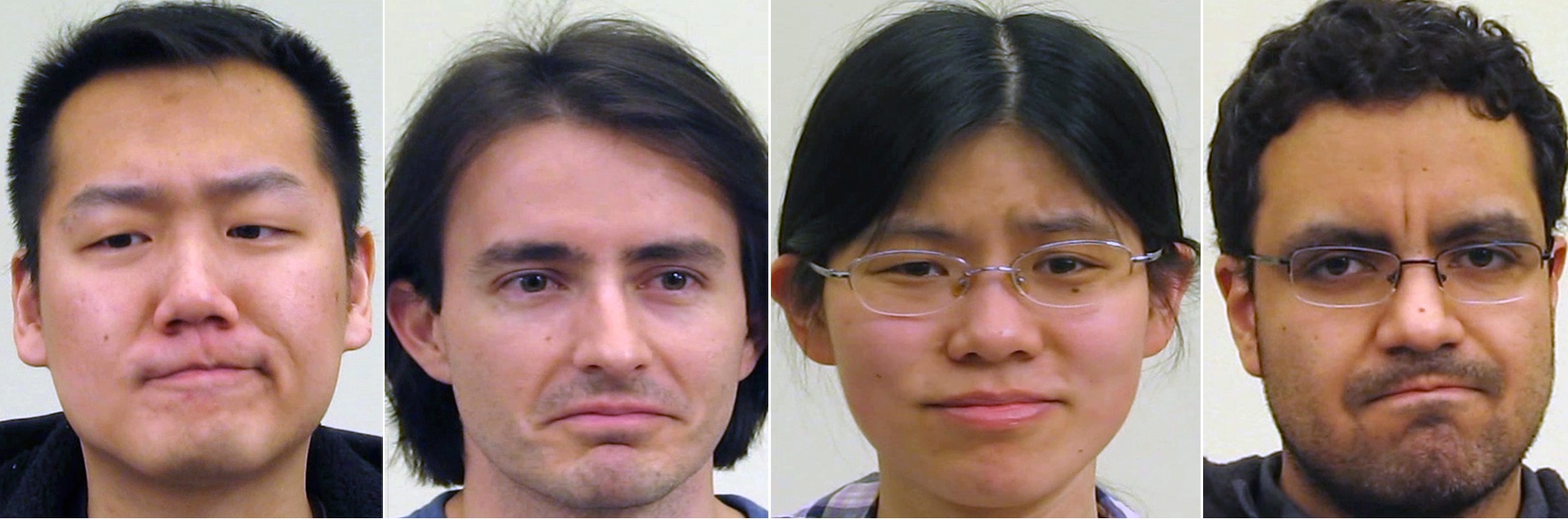

The facial expression indicating disagreement is universal, researchers say.

A furrowed brow, lifted chin and pressed-together lips — a mix of anger, disgust and contempt — are used to show negative moral judgment among speakers of English, Spanish, Mandarin and American Sign Language (ASL), according to a new study published in the May issue of the journal Cognition. In ASL, speakers sometimes use this "not face" alone, without any other negative sign, to indicate disagreement in a sentence.

"Sometimes, the only way you can tell that the meaning of the sentence is negative is, that person made the 'not face' when they signed it," Aleix Martinez, a cognitive scientist and professor of electrical and computer engineering at The Ohio State University, said in a statement.

Combo expression

Martinez and his colleagues previously identified 21 distinct facial emotions, including six basic emotions (happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise and disgust), plus combinations of those (happy surprise, for example, or the kind of happy disgust someone might express after hearing a joke about poop).

The researchers wondered if there might be a basic expression that indicates disapproval across cultures. Disapproval, disgust and disagreement should be foundational emotions to communicate, they reasoned, so a universal facial expression marking these emotions might have evolved early in human history. [Smile Secrets: 5 Things Your Grin Reveals About You]

The researchers recruited 158 university students and filmed them in casual conversation in their first language. Some of these students spoke English as a native tongue, while others were native Spanish, Mandarin Chinese or ASL speakers. These languages have different roots and different grammatical structures. English is Germanic, Spanish is in the Latin family and Mandarin developed independently from both. ASL developed in the 1800s from a mix of French and local sign language systems, and has a grammatical structure distinct from English.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But despite their differences, all of the groups used the "not face," the researchers found. The scientists elicited the expression by asking the students to read negative sentences or asking them to answer questions that they'd likely answer in the negative, such as, "A study shows that tuition should increase 30 percent. What do you think?"

Without a sign

As the students responded with phrases like, "They should not do that," their facial expressions changed. By analyzing the video of the conversations frame by frame and using an algorithm to track facial muscle movement, Martinez and his colleagues were able to show that a combination of anger, disgust and contempt danced across the speakers' faces, regardless of their native tongue. A furrowed brow indicates anger, a raised chin shows disgust and tight lips denote contempt.

The "not face" was particularly important in ASL, where speakers can indicate the word "not" either with a sign or by shaking their head as they get to the point of the sentence with the negation. The researchers found, for the first time, that sometimes, ASL speakers do neither — they simply make the "not face" alone.

"This facial expression not only exists, but in some instances, it is the only marker of negation in a signed sentence,” Martinez said.

The researchers are now building an algorithm to handle massive amounts of video data, and hope to analyze at least 10,000 hours of data from YouTube videos to understand other basic facial expressions and how people use expressions to communicate alongside language.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus