'Kidnapped' Sharks Use Their Noses to Navigate Back to Shore

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sharks may use their keen sense of smell to navigate the vast ocean, a new study finds.

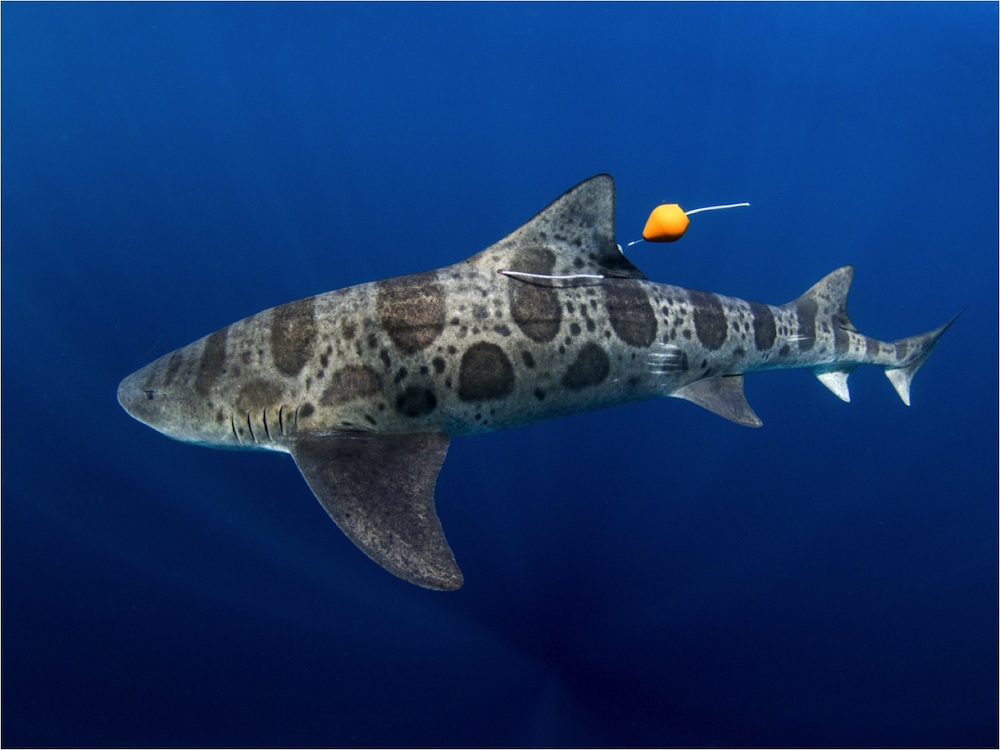

Researchers made the finding after catching leopard sharks (Triakis semifasciata), transporting them about 6 miles (9 kilometers) away from shore and stuffing some of the sharks' noses with Vaseline-soaked cotton. The scientists then released the sharks and tracked whether those with an impaired sense of smell had trouble finding their way back to shore.

The result? The sharks with nose plugs appeared lost, while those without stuffed noses were able to orient themselves to be homeward bound. [See Photos of the Researchers Tagging Leopard Sharks]

"We basically kidnapped these sharks from their home and confused them for an hour on the way out," said study lead researcher Andrew Nosal, a postdoctoral researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the Birch Aquarium in California. "Yet, within 30 minutes of being released in the middle of the ocean — a place that they had probably never been — they [those without nose plugs] knew exactly where shore was, which was really neat."

It's common knowledge that sharks are excellent navigators, often swimming along straight paths toward a target, but it's unclear what senses — such as sight, smell, or even electric or magnetic senses — help the animals plot a course, Nosal said.

However, there are clues that sharks rely heavily on smell. For instance, the olfactory bulb in the shark brain is larger in shark species that have higher navigational demands, Nosal said.

To investigate, he and his colleagues used baited hooks to capture 26 female leopard sharks off the coast of La Jolla in Southern California. Then, the researchers put the sharks in a holding tank on their boat, and covered it with a tarp so the sharks couldn't track their whereabouts using the sun. The researchers then drove about 6 miles offshore to a specific point.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They did the upmost to confuse the sharks, and all of their senses, traveling in random figure eights and hanging a strong magnet in the middle of the boat that spun randomly just in case the sharks were relying on magnetic signals to determine the location, Nosal said. Eleven of the sharks received nose plugs, and 15 received no plugs. (It's easy to plug a shark's nose — simply flip it on its back to calm it down, and stuff in the cotton, Nosal said.)

Because sharks breathe through their gills, not their noses, the temporary plugs didn't limit the animals' oxygen intake, said Jelle Atema, a professor of biology at Boston University Marine Program, who was not involved in the study.

Homeward bound

Before releasing the sharks, the researchers equipped each animal with an acoustic tag that stayed on the shark for 4 hours. On average, the sharks without the nose plugs made it about two-thirds of the way back home within the 4 hours, the researchers found.

"Amazingly, the sharks that could smell just fine, they basically found their way straight back to shore upon being released," Nosal said.

In contrast, the sharks with plugged noses made it only about one-third of the way home within the 4 hours, and their routes were more windy and random, he said. [8 Weird Facts About Sharks]

"These results demonstrate that olfaction contributes to shark navigation," Nosal said. "[But] it's clearly not the only sense they're using," because the sharks with plugged noses still managed to somewhat swim toward shore.

"That suggests that although olfaction appears to be important, it's not the only sense," Nosal said. "Future work will have to try to figure out the cues that they're using, other than smell, to find their way back."

The research is "a well-done study," Atema told Live Science.

"We can conclude that these coastal sharks can come home over a 9-km distance normally, but if you plug their nose, they are really hampered," Atema said.

The study raises more questions, including whether there is a chemical gradient in the water that the sharks use to smell their way home, Atema said. It's also possible that sharks don't rely much on smell, but that the act of losing their smelling ability throws them, which could explain their aimless swimming, he said.

The study was published online today (Jan. 6) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus