Poop Goes Mainstream: Fecal Transplants Get Past the 'Ick'

In an era of thousand-dollar pills and DNA-altering technologies, doctors are increasingly turning to a seemingly crude technique to treat chronic intestinal problems: poop transplants.

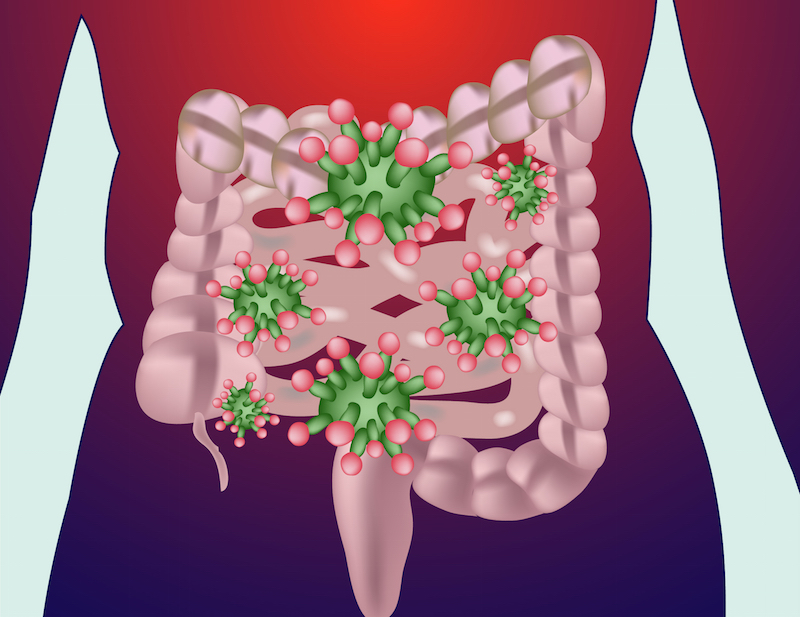

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), as it is properly called — and there's no sugarcoating the description here — is the process of placing the feces of a healthy person into the gut of a patient with an intestinal problem, such as chronic diarrhea or irritable bowel syndrome. The transplant occurs via a tube or capsule put down one's throat or up one's bottom.

The theory is that the transplanted stool — upward of 10 teaspoons' worth — introduces a healthy mix of bacteria that can overtake the harmful bacteria causing the intestinal problems. More than 4,000 gut specialists have gathered at the 80th annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology in Honolulu, Hawaii, and one item on their agenda is discussing the merits of FMT.

Several presentations on Monday (Oct. 19) addressed the key concerns about FMT. It is now established that the technique is safer, more effective and less expensive than standard antibiotic treatment for at least one common ailment: recurrent Clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection, researchers said. And this may be true for other diseases, as well, the scientists said. [The Poop on Pooping: 5 Misconceptions Explained]

C. diff, a gut-residing bacterium that can result in diarrhea so severe that the dehydration can be fatal, causes half a million infections and more than 29,000 deaths in the United States annually, according to a study published in February in the New England Journal of Medicine. People often contract the illness while they are in hospitals, after a treatment with antibiotics for some other sickness; the antibiotics can wipe out the population of good bacteria in one's gut and allow C. diff to flourish.

The standard treatment for initial C. diff infection, perhaps ironically, is more antibiotics, even though this poses a 20 percent risk for a recurrent infection, said Dr. Sahil Khanna of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who presented his results yesterday at the Hawaii meeting.

Khanna and his colleagues have developed a technique to accurately predict, for the first time, which patients are unlikely to benefit from antibiotic treatment, based on the number of various bacterial species in the patients' stool. Those who are at high risk of failing to improve with antibiotic treatment could consider FMT instead, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new prediction technique could help tailor more appropriate treatments for patients, Khanna said. This can be crucial in saving lives, given that recurrent C. diff infections are even more difficult to treat than the initial infection, he said. Vancomycin and other drug treatments have only a 40 to 50 percent success rate in treating recurrent C. diff, compared to FMT's nearly 90 percent success rate.

Dr. Zain Kassam, a research affiliate at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics, reported that FMT is not only more effective but also less expensive than vancomycin in treating recurrent C. diff. The infection amounts to $4.8 billion in health care costs yearly, and using FMT from a "stool bank" instead of the standard treatment could save the nation more than $121 million yearly, he calculated.

"Clinical guidelines for C. difficile — including [those from] the American College of Gastroenterology and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases — are moving towards FMT being recommended for the treatment of recurrent C. difficile given the emerging evidence," Kassam told Live Science.

Kassam is also chief medical officer at the MIT-affiliated OpenBiome, a nonprofit stool bank registered with the FDA that collects feces from donors, with the goal of expanding safe access to FMT. Donors are paid for their feces, and only 2.8 percent of candidate donors pass through the rigorous OpenBiome screening process, Kassam said. [The Poop on Pooping: 5 Misconceptions Explained]

Safety is a top concern with FMT, because feces can harbor unknown pathogens. And stool is more difficult to test than a drug or donated blood. Although there have been no reports of people getting sick as a result of FMT, a case study published earlier this year reported that a thin woman gained 34 lbs. (15 kilograms), and couldn't lose the weight, after receiving a fecal transplant from an obese donor. Thus, doctors began to wonder whether one could "catch" obesity through FMT.

But a new study, also presented at the Hawaii meeting, may ease those worries. Dr. Monika Fischer, of the Indiana University Department of Medicine in Indianapolis, found no risk of increased weight after FMT. Her study included 58 FMT patients, including 22 who received fecal transplants from overweight donors.

As promising as FMT appears to be, it is in legal limbo in the United States, as the FDA continues to mull over how to regulate the procedure. The FDA announced a policy in July 2013 that allows physicians to treat a person who has a C. diff infection with FMT only if a few conditions are met: The patient must be failing to respond to standard therapy, and the doctor must obtain informed consent, explain the risk and benefits, and tell the patient that FMT is investigational.

But to treat patients with C. diff that is not recurrent, or those who have another intestinal disorder, such as irritable bowel syndrome or Crohn's disease, doctors first need to complete an Investigational New Drug (IND) application. Some doctors say this requirement is cumbersome and discourages use of the treatment.

"Our stool bank has a deep respect for the regulatory challenges the FDA is facing in this rapidly evolving field," Kassam said. "Overall, enforcement discretion paints a picture that the FDA recognizes that FMT is a square peg and doesn't fit nicely into a round hole like other therapies," such as blood transfusions and other tissue donations, he said.

As the field grows and evidence mounts that FMT may treat diseases beyond C. diff, Kassam said that the FDA will face unique challenges balancing public health, economic impact and safety for this "potentially paradigm-shifting treatment."

Other studies, mostly from non-U.S. institutions, have found that FMT is beneficial for people with inflammatory bowel disorders such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. One of the largest studies, published this year, was a randomized control trial of 70 patients with ulcerative colitis. The researchers, at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, found significant improvements in patients who received FMT compared with those who received a placebo treatment.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.