Bigger Earthquake Coming on Nepal's Terrifying Faults

Nepal faces larger and more deadly earthquakes, even after the magnitude-7.8 temblor that killed more than 4,000 people on Saturday (April 25).

Earthquake experts say Saturday's Nepal earthquake did not release all of the pent-up seismic pressure in the region near Kathmandu. According to GPS monitoring and geologic studies, some 33 to 50 feet (10 to 15 meters) of motion may need to be released, said Eric Kirby, a geologist at Oregon State University. The earth jumped by about 10 feet (3 m) during the devastating April 25 quake, the U.S. Geological Survey reported.

"The earthquakes in this region can be much, much larger," said Walter Szeliga, a geophysicist at Central Washington University.

Seismologists have extensively studied the possibility of damaging earthquakes in the central Himalayas. Through analyzing written histories, looking for clues from damaged buildings and digging along faults, researchers know of several damaging earthquakes in the past, but not their precise size. [See Photos of This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

Nepal was overdue for a major earthquake, said Marin Clark, a geophysicist at the University of Michigan. "It has been a long time since the last big rupture, so this is not unexpected," Clark said.

One of the region's most devastating recent quakes occurred in 1934, when a magnitude-8.2 earthquake killed over 8,500 people in Kathmandu. Before then, the last time such an immense quake struck Kathmandu was on July 7, 1255. That quake killed about 30 percent of the population. The region west of Kathmandu has been seismically quiet since June 6, 1505, when a great earthquake toppled buildings from Tibet to India.

Crash zone

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

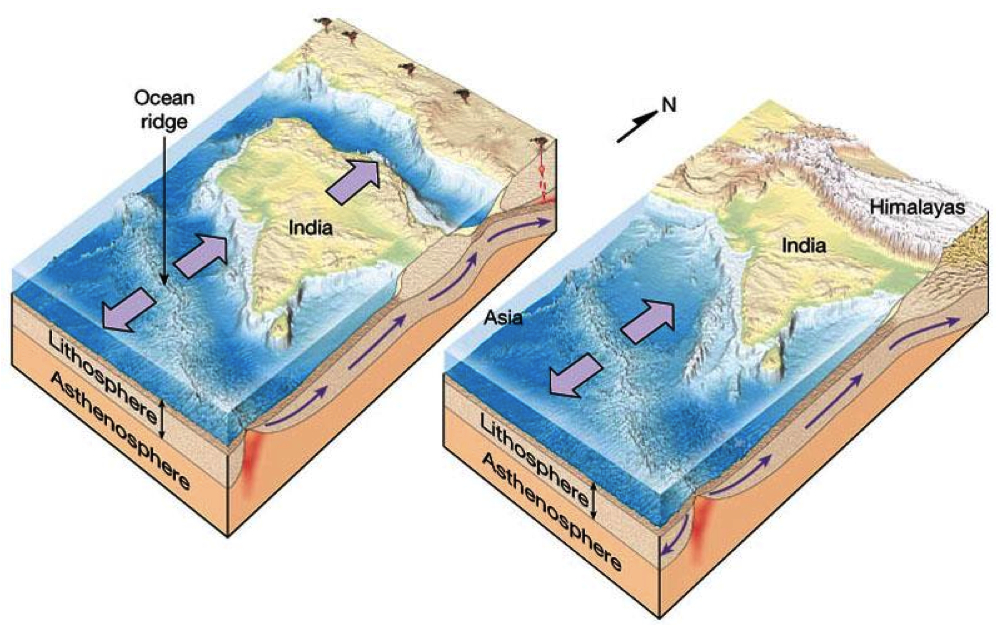

Nepal is one of the world's most earthquake-prone regions because it lies at the head-on collision between two tectonic plates. India is slamming into Asia, and neither wants to give. Both India and Asia are continental crust, of the same average density. So instead of one plate sinking beneath the other, such as is happening at the ocean-continent plate collision offshore South America, the Earth's crust crumples. Slices of India peel off and slowly squeeze under Asia, while Asia is mashed upward, forming the Himalayas.

India and Asia collide at about eight-tenths of an inch (2 centimeters) per year. Most of that energy is loaded onto earthquake faults as elastic strain because the faults are stuck together. Loading a fault is like squeezing a spring; an earthquake releases the built-up energy similar to an uncoiling spring.

Scientists think earthquakes that are magnitude 7.8 in size can't release all of the strain between India and Asia. Instead, history suggests most of the stored energy gets uncorked as earthquakes that are magnitude 8 or greater, according to geologic studies. It would take scores of magnitude-7 quakes to accommodate all of the plate motion, but only a handful of midsize, magnitude-8 quakes, or one magnitude 9. (The energy released by a quake increases by a factor of 30 with each additional point in magnitude.) [Video: What Does Earthquake 'Magnitude' Mean?]

"It seems likely that the amount of slip in this earthquake probably didn't make up for the complete deficit," Kirby said.

The April 25 earthquake struck on one of the many thrust faults that mark the boundary between the two plates. Thrust faults are the most terrifying of all faults because they lie at an angle. This shallow angle means a massive part of the Earth's crust can lurch during an earthquake. Steeper faults quickly grow too warm and soft to break; as rocks get deeper, they flow like putty, Szeliga said. During the Nepal temblor, a piece of crust roughly 75 miles (120 kilometers) long and 37 miles (60 km) wide jogged 10 feet (3 m) to the south. The fault angled only 10 degrees from the surface, and the quake was only 9 miles (14 km) deep.

"This one was relatively shallow, which intensifies the surface shaking," Clark said.

From seismic readings, many scientists suspect the fault did not break all the way to the surface, like the 1994 Northridge earthquake in Los Angeles. That's another indication that the earthquake did not unleash all of the stored strain in the region, Kirby said. The seismic instruments can detect where the strongest motion occurred on the fault.

However, even without a surface trace, GPS instruments and InSAR (radar from satellites) will provide precise tracking of how the ground shifted during the earthquake, Szeliga said. The data will help ground-truth scientist's models of Himalayan tectonics.

"Now's the chance to see who made predictions that were even remotely testable, and if they stand up," Szeliga said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.