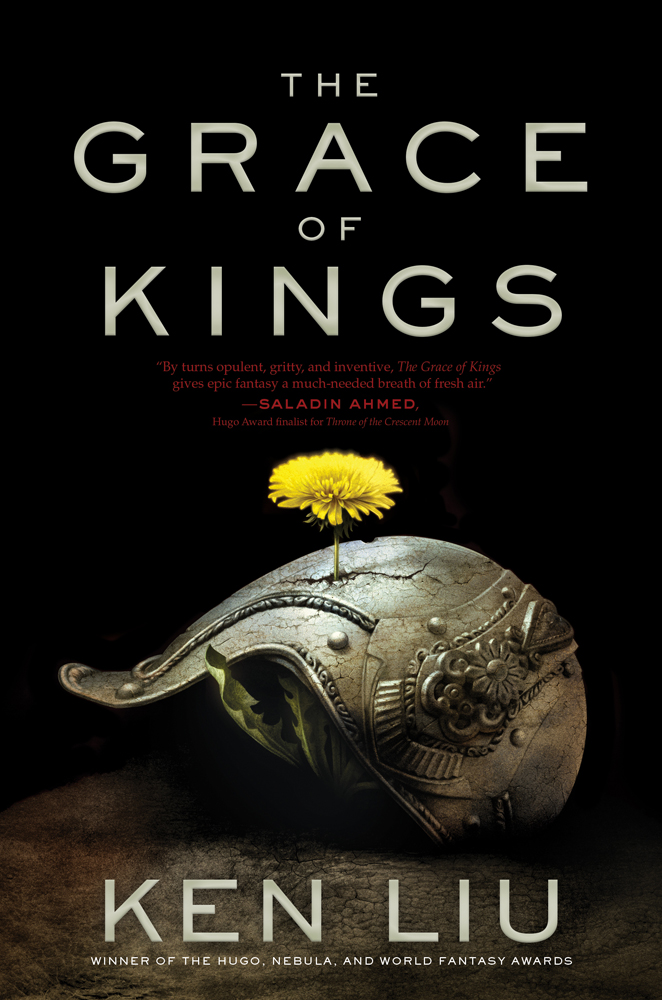

Ken Liu is an author whose fiction has appeared in such outlets as F&SF, Asimov's, Analog, Strange Horizons, Lightspeed, and Clarkesworld. Liu is the recipient of the Hugo Award, the Nebula Award, and The World Fantasy Award, all for "The Paper Menagerie," and won an additional Hugo for his story "Mono No Aware." Liu's debut novel, "The Grace of Kings" (Saga, 2015), the first in a fantasy series, will be published in April 2015. Liu contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights

In 206 B.C., the first imperial dynasty of China, the Qin, collapsed as a result of misrule and peasant rebellions. Contending warlords divided China into more than a dozen small kingdoms engaged in mutual warfare, until Xiang Yu, ruler of Western Chu, and Liu Bang, ruler of Han, emerged as the two dominant powers and fought a bitter war for control of all of China. The Chu-Han Contention, as the war came to be called, led to the founding of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), which is often considered one of the golden ages of China's history for its technological and cultural development.

When building the world for "The Grace of Kings" — a loose, fantasy reimagining of the Chu-Han Contention — I set out deliberately to create a new aesthetic inspired by East Asian antiquity, something I call "silkpunk."

Like steampunk, silkpunk is a genre that straddles the boundary between science fiction and fantasy. Thus, while the book features technology like silk-draped airships, soaring battle kites, underwater boats powered by steam engines, and lodestone-based metal detectors, it also contains magical tomes that describe our desires better than we know them ourselves, gods who regret the deeds done in their names, and giant sea beasts that bring about tsunamis and storms — but also guide soldiers safely to shores.

In designing the technology, I was guided by the theories of W. Brian Arthur, author of the book "The Nature of Technology," (Free Press, 2009) when considering how such systems evolve. Historically, new technologies are derived by recombining old technologies in novel ways, each component a technology on its own, harnessing some specific natural phenomenon. This hierarchical, recursive and combinatorial vision of technology suggests a natural analogy with language, which is also hierarchical, recursive and combinatorial. What I needed was to invent a new technology vocabulary and grammar.

Whereas the technological vocabulary and grammar of steampunk are based on chrome, glass and steam, and on mechanical precision and rigidity — echoed in the look of the corseted body — the vocabulary and grammar of silkpunk are based on organic materials and biomechanics.

Thus, the machines in the book are constructed from bamboo, silk, paper, coconut and leather, and are powered by wind, water, ox sinew or muscle. The movements of the assemblies and subassemblies imitate animals, explicitly noted as inspirations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Silkpunk flying machines like giant kites and hot-air balloons are directly inspired by classical East Asian sources. For example, Chinese records indicate that the first kites were constructed more than 2,400 years ago and found military application as signaling devices and measuring tools (and perhaps even for spying). Kongming lanterns, probably invented as early as the 3rd century B.C., were small paper hot-air balloons also used for signaling and message delivery. [Science Fiction Barely Ahead of Space Exploration Reality]

From that basis, I extended the technology to include airships. Constructed from bamboo and silk, these ships use an unnamed gas that is likely helium. To carry through the silkpunk aesthetic, the airships are described as being explicitly inspired by living organisms that also rely on the mysterious gas for lift, and their mechanism for buoyancy regulation (a perennial problem in real-world airship design) is modeled after the swim bladders of fish — that is, the gas bags are compressed to reduce lift and are allowed to expand to increase lift. Propelled by giant, feathered oars, and lit from within their hulls at night, these silkpunk airships move through the sky in a manner reminiscent of jellyfish swimming through an empyrean sea, the inner bags of lift gas contracting and expanding to maintain equilibrium.

Such technology colors every aspect of the world of "The Grace of Kings," the Islands of Dara — material culture, military strategy, economics, the metaphors used by the characters.

It's perhaps somewhat uncommon to infuse an epic fantasy novel with so much technology. Indeed, in "The Grace of Kings," the invention of various technologies and their adoption determine the fates of states and the outcomes of wars, and attitudes about technology are integral to the characterization of such things.

But as a technologist at heart, I wanted to use a new language of technology to give a fresh perspective on politics and history, and tell a story of change, rebellion and revolution. (This explains the "-punk" part.) In other words, I wanted to suggest that theories of technology could be applied to realms we don't normally think of as "technologies," such as taxation systems, bureaucratic organization and military tactics.

Thus, in my novel, I spend a great deal of time working through how armies with premodern technology might adopt their tactics to the appearance of air power; how battle kites carrying heroes into aerial duels can be combined with social engineering to sustain an outdated form of warfare — personal combat between commanders — into the era of mass armies; and how naval supremacy may be subverted by the invention of underwater boats, a shift that is echoed in similar shifts in the economic and political system. [Care for Some Science in Your Science Fiction? (Op-Ed)]

The emphasis on "technology" as a visual and narrative language in the novel delighted me as a writer. I loved inventing new machines and working through how the machines could be derived from technologies already extant in the world, and how such machines changed the options available to the characters and affected their thinking. The silkpunk aesthetic shaped the story, and I hope it added a sparkle of magic.

Read an excerpt from "The Grace of Kings" here .

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.