The Microbes That Ride the NYC Subway with You

For all the bizarre sights on the subway in New York, the tiny, unseen organisms lurking in the train stations might make up the city's most colorful freak show.

A team of scientists collected cotton-swab samples from the turnstiles, emergency exits, MetroCard kiosks, benches, hand rails and trash cans in all 468 stations that make up New York City's sprawling subway system, which provides 1.7 billion rides every year.

The researchers found some unusual results, from traces of pathogens like the plague and anthrax, to marine microbes thought to be native to Antarctica, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, bacteria from mozzarella cheese. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About Your Microbiome]

Some New Yorkers may be unnerved to know they're riding among hundreds of miniscule species, but the scientists said there's no reason to worry or start wearing gloves on the train. Most of the 637 known bacterial, viral, fungal and animal DNA samples the scientists collected are from organisms that don't cause disease or are found on the human body anyway, the report found.

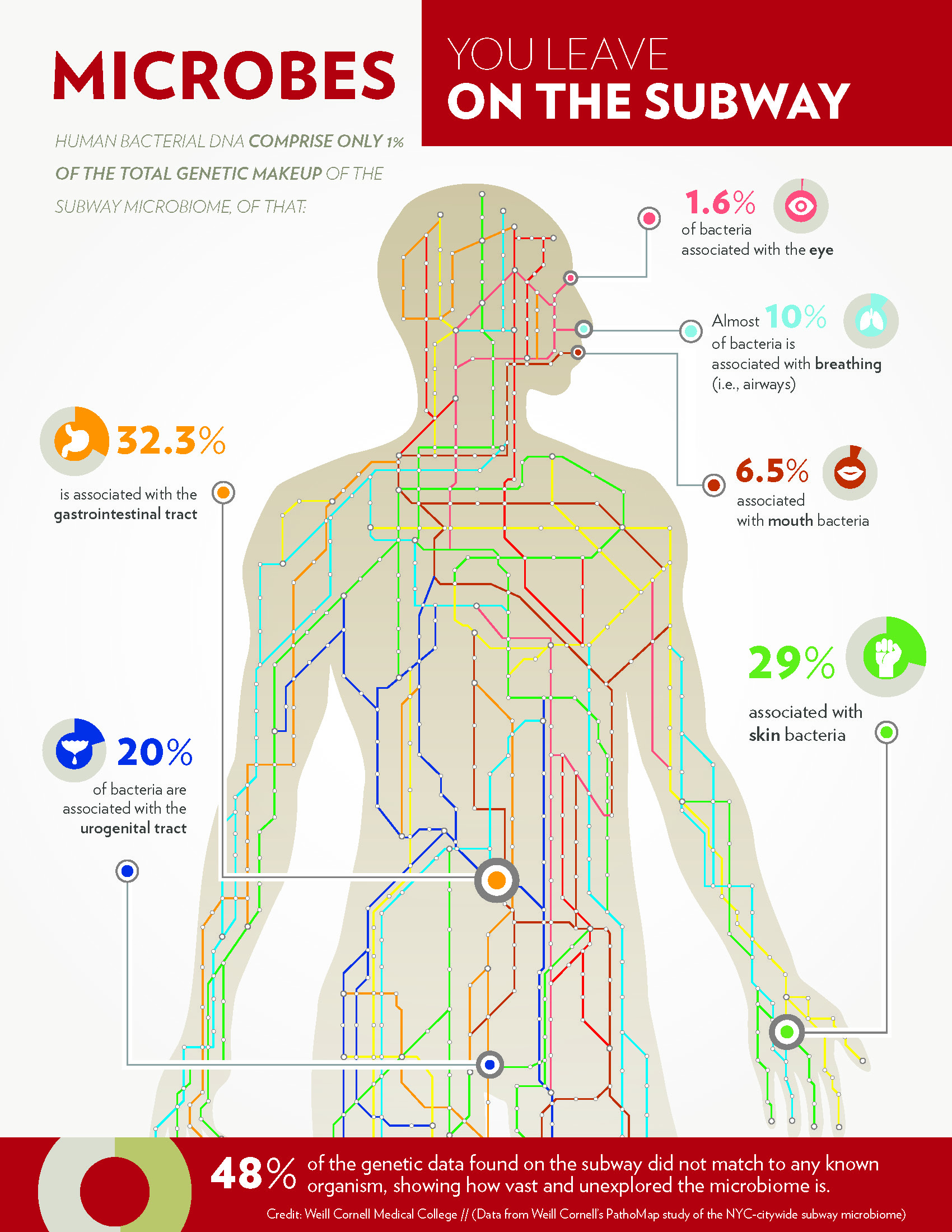

"Our data show evidence that most bacteria in these densely populated, highly trafficked transit areas are neutral to human health, and much of it is commonly found on the skin or in the gastrointestinal tract," Christopher Mason, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, said in a statement. "These bacteria may even be helpful, since they can out-compete any dangerous bacteria."

Bacteria were the most common organisms (46.9 percent) found in the subway system, and about 57 percent of those bacteria have never been linked to human disease. Another 31 percent of the detected bacteria were classified as opportunistic pathogens that could potentially infect people with weakened immune systems.

The remaining 12 percent had some link to disease, such as antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which were present in 27 percent of the samples collected in the study. Two samples had DNA traces of anthrax, and another three samples had a DNA molecule associated with bubonic plague. But these organisms did not appear to be viable and they were not linked to any recent outbreak of disease, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They are instead likely just the co-habitants of any shared urban infrastructure and city, but wider testing is needed to determine how common this is in other cities," Mason said. "Despite finding traces of pathogenic microbes, their presence isn't substantial enough to pose a threat to human health."

Another strange discovery came at the South Ferry Station, at the tip of Lower Manhattan, which was completely submerged in seawater when Superstorm Sandy barreled through the New York region in late October 2012. Two years later, that subway station's bacterial profile still resembles a cold marine ecosystem, with traces of bacteria such as Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis, which is found in oysters, and Shewanella frigidimarina, which was previously assumed to be an Antarctic species, associated with fish.

There's still a lot of potential for scientific exploration in the subway system, the researchers said. Mason and his colleagues couldn't even identify half of the DNA collected in their study, meaning these sequences didn't match any organism known to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But those databases may need to be updated. The study researchers found that mountain pine beetle DNA was more prevalent than human DNA in New York's subway stations. However, the presence of beetle DNA might actually represent the presence of a yet-to-be-sequenced genome from another, more common insect, such as the cockroach, which isn't in the NCBI database yet, the researchers said in their report.

The findings were published in the journal Cell Systems this week, and the researchers say they hope the cache of data will serve as a baseline to help city officials monitor disease, bioterrorism threats and public health.

Data from the study have been uploaded into an interactive PathoMap. But unless you're well-versed in bacterial taxonomy, you might have a hard time deciphering which bugs have been found at your subway stop. The Wall Street Journal's interactive graphic puts the findings in more plain language, showing the locations of bacteria associated with sunscreen, dysentery, Italian cheese, staph infections, kimchi and sauerkraut.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.