Tsunami Science: Advances Since the 2004 Indian Ocean Tragedy

The Indian Ocean tsunami was one of the worst natural disasters in history. Enormous waves struck countries in South Asia and East Africa with little to no warning, killing 243,000 people. The destruction played out on television screens around the world, fed by shaky home videos. The outpouring of aid in response to the devastation in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and elsewhere was unprecedented.

The disaster raised awareness of tsunamis and prompted nations to pump money into research and warning systems. Today (Dec. 26), on the 10th anniversary of the deadly tsunami, greatly expanded networks of seismic monitors and ocean buoys are on alert for the next killer wave in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific and the Caribbean. In fact, tsunami experts can now forecast how tsunamis will flood distant coastlines hours before the waves arrive.

But hurdles remain in saving lives for everyone under the threat of tsunamis. No amount of warning will help those who need to seek immediate shelter away from beaches, disaster experts said. [10 Tsunamis That Changed History]

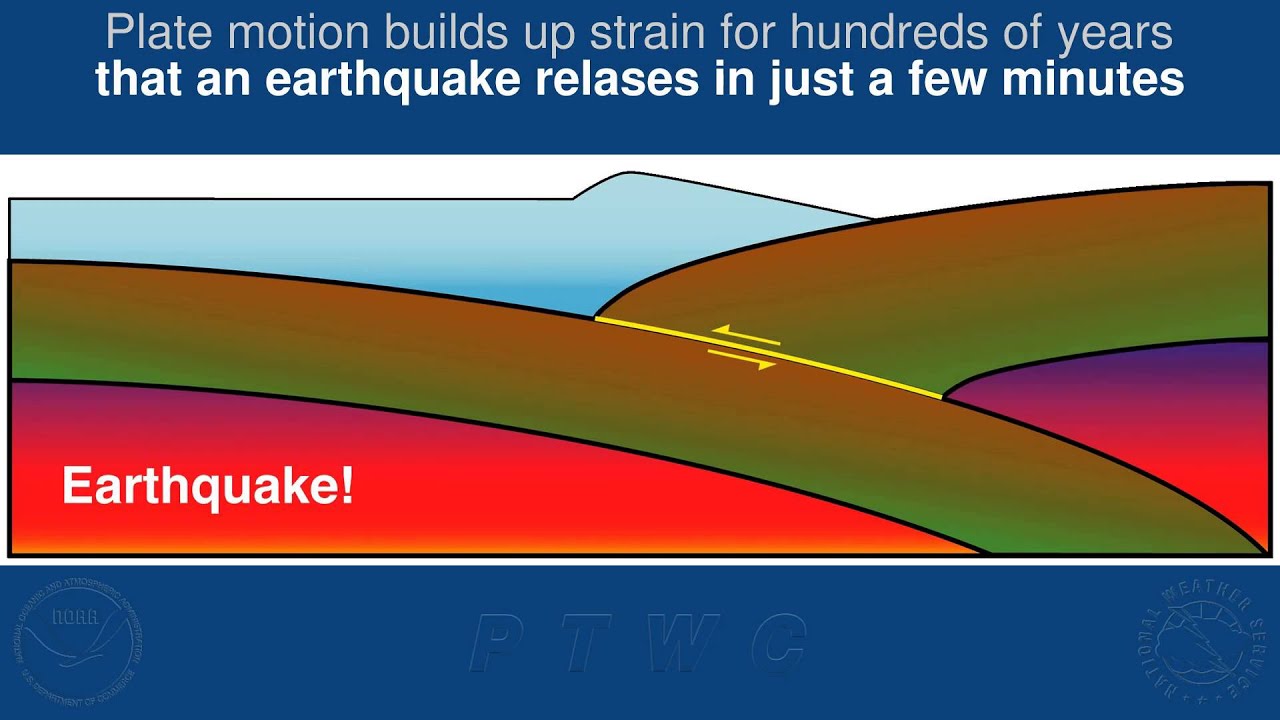

"A lot of times, you're not going to get any warning near these zones where there are large earthquakes, so we have to prepare the public to interpret the signs and survive," said Mike Angove, head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) tsunami program. In 2004, the tsunami waves approached coastal Indonesia just nine minutes after the massive magnitude-9.1 earthquake stopped shaking, Angove said.

On alert

Since 2004, geologists have uncovered evidence of several massive tsunamis in buried sand layers preserved in Sumatran caves. It turns out that the deadly waves aren't as rare in the Indian Ocean as once thought. "We had five fatal tsunamis off the coast of Sumatra prior to 2004," said Paula Dunbar, a scientist at NOAA's National Geophysical Data Center. Over the past 300 years, 69 tsunamis were seen in the Indian Ocean, she said.

Despite the risk, there was no oceanwide tsunami warning system in the region. Now, a $450 million early-alert network is fully operational, though it is plagued with equipment problems. (Even the global monitoring network loses 10 percent of its buoys each year, according to NOAA.) Essentially built from scratch, the $450 million Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (IOWTS) includes more than 140 seismometers, about 100 sea-level gauges and several buoys that detect tsunamis. More buoys were installed, but they have been vandalized or accidentally destroyed. The buoys and gauges help detect whether an earthquake triggered a tsunami.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The global network of Deep-Ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART) buoys, which detects passing tsunami waves, has also expanded, from six buoys in 2004 to 60 buoys in 2014, Angove said.

Regional tsunami alert centers have been built in Australia, India and Indonesia. Scientists at the centers decide whether a tsunami is likely based on information from the network of sensors, estimate the probable size, then alert governments to get the warning out through sirens, TV, radio and text alerts.

Getting the warnings down to people living in remote coastal areas is one of the biggest hurdles for the new system. Not all warnings reach the local level. And not every tsunami earthquake is strong enough to scare people away from shorelines. In Sumatra's Mentawai Islands, a 2010 tsunami killed more than 400 people because residents failed to evacuate in the short time between the earthquake and the tsunami's arrival. The shaking was simply not strong enough to trigger people's fear of tsunamis, even though islanders had self-evacuated after a 2007 earthquake, according to an investigation by the University of Southern California's Tsunami Research Center. There was also no clear-cut warning from the regional tsunami alert system.

"Tsunami earthquakes remain a major challenge," Emile Okal, a seismologist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, said Dec. 15 at the American Geophysical Union's (AGU) annual meeting in San Francisco. [Waves of Destruction: History's 8 Biggest Tsunamis]

From hours to minutes

Another hurdle is learning how to accurately forecast reflected tsunami waves. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami ricocheted off island chains, and some of the worst flooding arrived unexpectedly late in places like Sri Lanka and Western Australia.

"I found a boat on the middle of the road, and at that point knew it was a tsunami," recalls Charitha Pattiaratchi, a University of Western Australia tsunami expert who was driving on a coastal Sri Lankan road on Dec. 26, 2004. "I came to the conclusion that I was safe. Well, I was wrong," Pattiaratchi said at the AGU briefing. "I turned back to Colombo and told people don't worry, it's safe, there's no more waves coming, but 20 minutes later there was 7 meters [23 feet] of water where I had been standing, and two hours later there were still more waves coming."

A tsunami warning can go out just five minutes after a submarine earthquake raises or lowers the seafloor, thus launching a tsunami. For more detailed predictions of the wave's impact, such as the extent of flooding, scientists rely on data collected by seismometers, GPS stations, tide gauges and buoy systems, which is relayed by satellite to warning centers. Computer models then convert the data into detailed tsunami simulations, which are based on more than 2,000 real-life examples.

"A tsunami is like dropping a rock in a pond, but it doesn't go uniformly out. It is guided by underwater mountain ranges and valleys," Eddie Bernard, former director of NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, said at a Dec. 15 news conference held during the AGU meeting.

After an earthquake, scientists with NOAA's tsunami warning centers now spend about an hour working out the details of a tsunami forecast, said Vasily Titov, director of NOAA's Center for Tsunami Research. The results project when the wave will arrive at shorelines and harbors, estimate tsunami-induced currents and gauge the height of the waves.

The agency's goal is to dramatically reduce that hour-long delay. "We're now at the point where we want to do it in five minutes," Titov said. That means building out the seismic network, getting a faster response from the sea-level sensors and speeding up the computer forecasts.

"When these three components come together, then we can save everybody," Titov said.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.