Real-Life Tractor Beam Pulls in Particles

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The invisible force that pulls in the Millennium Falcon spacecraft to the Death Star in "Star Wars" movies is still far from becoming a reality, but physicists have developed a miniature version of sorts: a tractor beam that can reel in tiny particles.

The laser-based retractor beam pulled the particles a distance of about 8 inches (20 centimeters), which is 100 times farther than any previous experiments with tractor beams.

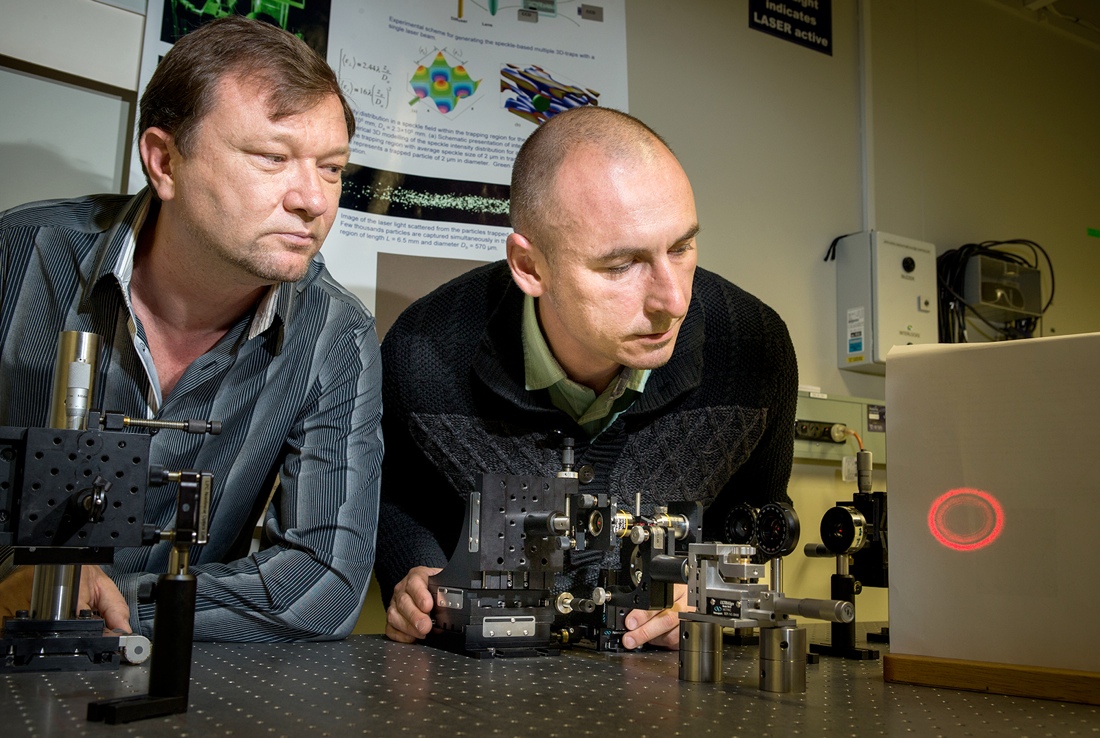

"Because lasers retain their beam quality for such long distances, this could work over meters," study researcher Vladlen Shvedov, research fellow at the Australian National University, said in a statement. "Our lab just was not big enough to show it." [Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts]

During the experiment, the researchers used a laser that projected a doughnut-shaped beam of light with a hot outer ring and cool center. They used the light beam to suck in tiny glass spheres, each of which measured about 0.2 millimeters (0.008 inches) wide.

Not only did the researchers move the glass spheres farther than had been demonstrated in previous experiments, but they used a different technique altogether. Other retractor beams rely on the momentum of light particles in the laser beam to reel in mass. In those experiments, the momentum from the light particles shooting out of the laser is transferred to the target that the laser is hauling in. However, that technique works well only in a vacuum that is shielded from other free-floating particles that can interfere with the momentum transfer.

The new technique takes advantage of heat energy. During the experiment, heat from the laser warmed up the air around the tiny spheres. The spheres absorbed some of the heat until their surfaces were sprinkled with hotspots. Air particles that run into the hotspots ricochet off and cause the spheres to repel in the opposite direction. The trick is to make the back of the sphere hotter than the front of the sphere, said study researcher Cyril Hnatovsky, a research fellow at the Australian National University.

"The gas molecules interacting with the hotspot on the back surface will push the sphere against the light flow," Hnatovsky told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The physicists can manipulate the particles by controlling where the hotspots form. That means the beam not only pulls in particles, but it can also push them or create an even distribution of hotspots and hold the spheres suspended in place.

Thetechnique could be applied to control things like air pollution by pulling out toxic particles, Hnatovsky and his colleagues said. But adapting the technique to longer distances will be tricky, he added.

"I see no difference between 0.5 or 1 or 2 meters [1.6 or 3.3 or 6.6 feet]," Hnatovsky said. "Ten to 20 meters [33 to 66 feet] is a real challenge."

The new study was published Oct. 19 in the journal Nature Photonics.

Follow Kelly Dickerson on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus