New Tech Helps Pilots Navigate Dangerous Volcanic Ash Plumes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

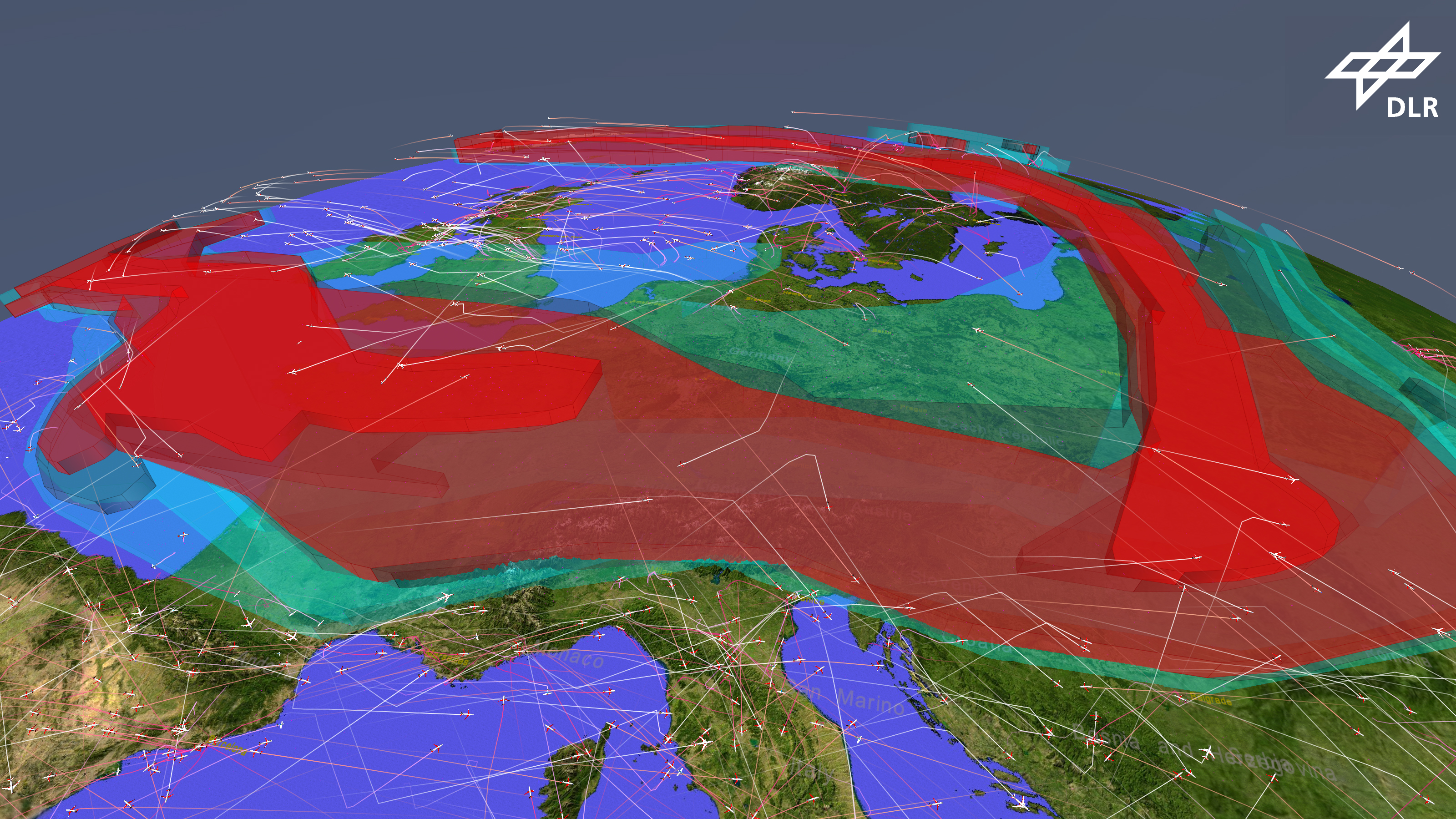

New technology to detect volcanic ash that threatens airplanes could help prevent a repeat of the air traffic chaos that followed a 2010 volcanic eruption in Iceland.

Private companies are developing infrared detectors to scout out ash levels in the air, ahead of flying aircraft. The plane-mounted sensors will give pilots time to divert around dangerous ash plumes.

Government agencies are also working to improve their space-based monitoring systems. With satellites, scientists can detect tiny ash particles, but predicting where aircraft can safely fly is still a major hurdle. [Big Blasts: History's 10 Most Destructive Volcanoes]

"The key issue for us is to develop an integrated monitoring and response system for future volcanic crises that can be used to respond quickly in the event of the formation of an ash cloud from Iceland," Hans Schlager, head of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the German Aerospace Center, said in a statement.

Ash particles are jagged and sharp. The fine, glassy rock can damage and abrade engines, windows and other structures on aircraft flying at all altitudes.

The German Aerospace Center, also called DLR, is upgrading its ash-detection system and its air traffic control methods so that fewer planes will be stuck on the ground the next time a volcano in Iceland spews ash toward Europe. Tests are being run based on the 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano, when approximately 100,000 flights had to be canceled and 10 million passengers were stranded.

The DLR researchers said that if they had employed these newly developed models for predicting the complex movement of ash through the air and rejiggered algorithms for rerouting flights around bad weather, they think they could have doubled the number of flights on a single day during the crisis. Instead of just 5,000 flights on April 17, 2010, around 10,700 flights could have taken place.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Volcanic ash plumes regularly plague travelers, though the delays are typically on a more regional scale than the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, which cost airlines $1.7 billion in lost revenue, according to the International Air Transport Association, an industry group.

For example, North Sumatra's Kualanamu International Airport temporarily halted operations in 2013 following eruptions at Mount Sinabung, some 30 miles (48 kilometers) away. And blasts at Sicily's Mount Etna often stop flights at Catania's Fontanarossa Airport. Air travel between Australia and Bali was disrupted in May by Indonesia's Sangeang Api volcano.

NASA researchers are also looking for new ways to improve forecasts of volcanic ash hazards. Satellites such as the CALIPSO mission, which tracks atmospheric particles, can also locate ash days to weeks after an eruption, according to a study published in the September 2013 Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. The satellite can distinguish between ash plumes and clouds, and can provide more accurate forecasts, the researchers said.

"The Icelandic eruption — such a dramatic event — made us take a hard look at what each of our satellites can tell us," John Murray, associate program manager for the NASA Applied Sciences Program's natural disasters focus area, said in a statement. "We knew we needed to understand how to integrate them to make better forecasts.

No system will be perfect, though. That's why Nicarnica Aviation in Kjeller, Norway, has invented an ash detector that attaches to a plane, so pilots receive a warning before flying into dangerous particles.

The infrared camera is now undergoing ground-based testing at Iceland's Holuhraun eruption, where it caught toxic volcano tornados spinning in sulfurous gas spewing from the fiery lava. The sensors have also received air trials from Airbus and EasyJet.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus