Religion Doesn't Make People More Moral, Study Finds

The moral high ground seems to be a crowded place. A new study suggests that religious people aren't more likely to do good than their nonreligious counterparts. And while they may vehemently disagree with one another at times, liberals and conservatives also tend to be on par when it comes to behaving morally.

Researchers asked 1,252 adults of different religious and political backgrounds in the United States and Canada to record the good and bad deeds they committed, witnessed, learned about or were the target of throughout the day.

The goal of the study was to assess how morality plays out in everyday life for different people, said Dan Wisneski, a professor of psychology at Saint Peter's University in Jersey City, New Jersey, who helped conduct the study during his tenure at the University of Illinois at Chicago. [8 Ways Religion Impacts Your Life]

The study's findings may come as a shock to those who think religious or political affiliationhelps dictate a person's understanding of right and wrong.

Wisneski and his fellow researchers found that religious and nonreligious people commit similar numbers of moral acts. The same was found to be true for people on both ends of the political spectrum. And regardless of their political or religious leanings, participants were all found to be more likely to report committing, or being the target of, a moral act rather than an immoral act. They were also much more likely to report having heard about immoral acts rather than moral acts.

However, there were some differences in how people in different groups responded emotionally to so-called "moral phenomena," Wisneski said. For example, religious people reported experiencing more intense self-conscious emotions — such as guilt, embarrassment, and disgust — after committing an immoral act than did nonreligious people. Religious people also reported experiencing a greater sense of pride and gratefulness after committing moral deeds than their nonreligious counterparts.

Liberals and conservatives also tended to think of moral phenomena in different ways. In other words, though they seemed to experience the same amount of moral and immoral acts, they had different ways of talking about these experiences.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Liberals more often mention moral phenomena related to fairness and honesty," Wisneski said. "Conservatives more often mention moral phenomena related to loyalty and disloyalty or sanctity and degradation."

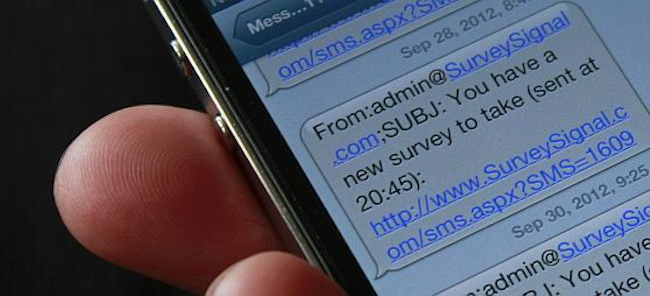

For three days, participants received five text messages a day that included a link to the study's mobile website, where they could record any moral phenomena that they had experienced in the past hour via their smartphones. On average, participants reported one moral experience per day, Wisneski said.

This approach to studying morality is a far cry from previous studies, most of which have been conducted in a laboratory setting and have focused on studying peoples' responses to hypothetical moral dilemmas, according to Wisneski.

"As far as I know, this is the first study that's used this kind of lived-experience approach to track morality as it's happening," he said.

In the future, Wisneski and his colleagues hope to use their smartphone-enabled approach to study morality in a more nationally representative sample of people, he said. They also think this method could be applied to studying morality in different parts of the world, such as Asia and the Middle East, where religious and political beliefs may have different influences than on people in North America.

The morality study, which was conducted by psychologists at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the University of Cologne, in Germany, and the University of Tilburg, in the Netherlands, was published online today (Sept. 11) in the journal Science.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus