What the Deep Sea Sounds Like

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

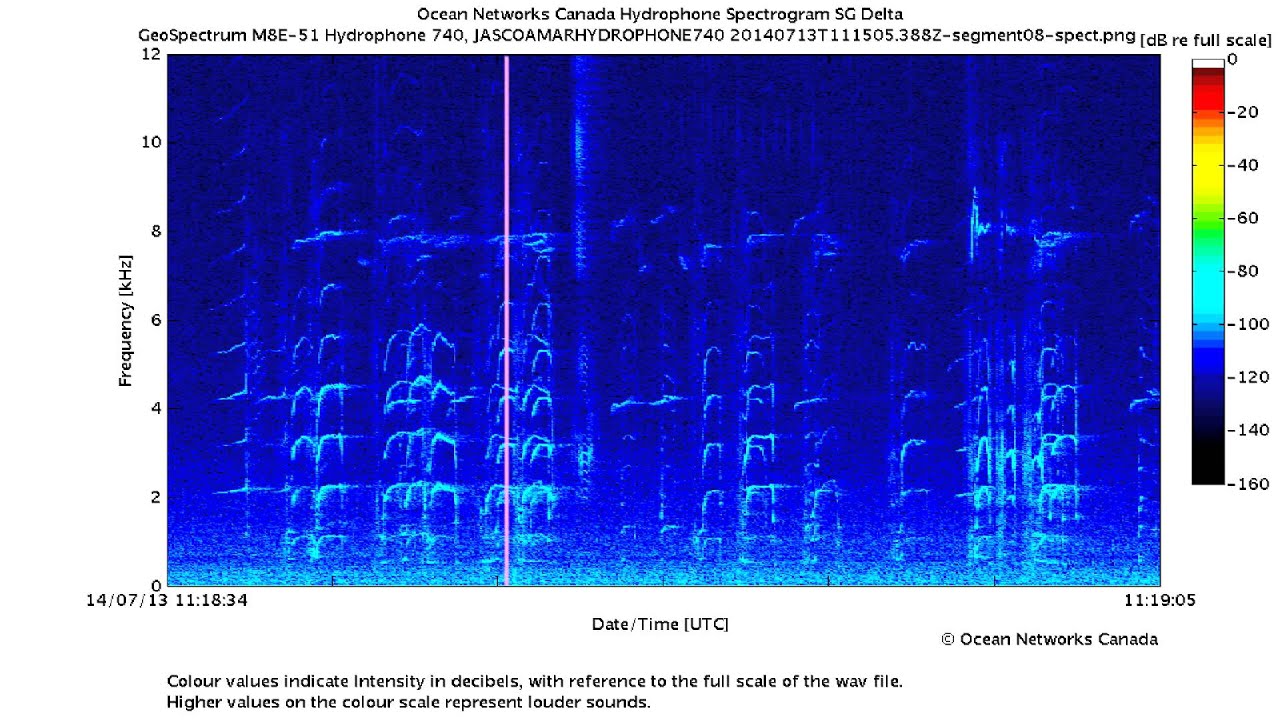

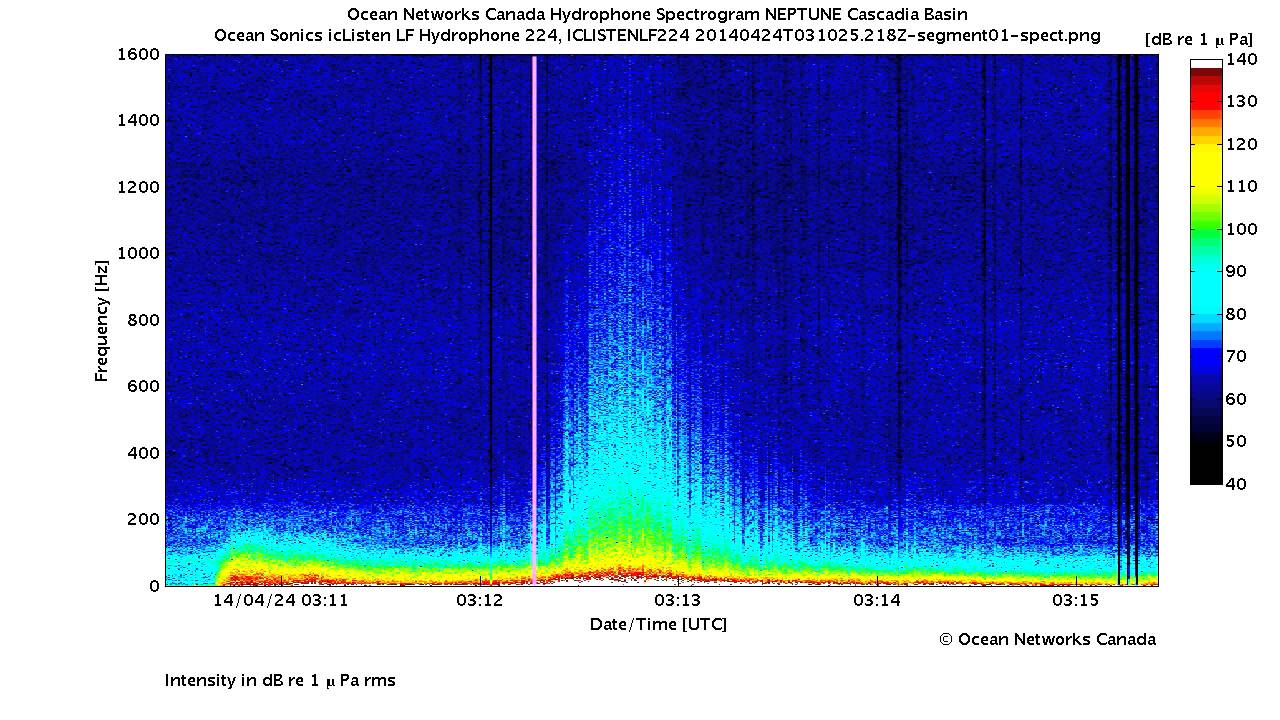

At the bottom of the ocean, a network of underwater microphones eavesdrops day in and day out on the squeaky laments of whales, the rumbles of earthquakes and the drone of passing ships.

These sounds can reveal a lot about the mysterious world beneath the waves, from how human noise affects communication between marine mammals to the classified movements of naval submarines — which hasn't escaped the notice of the U.S. and Canadian militaries.

The research organization Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) in Victoria, British Columbia, operates three major ocean observatories that collect long-term data on the biology, geology and chemistry of marine and coastal waters. The VENUS coastal observatory lies in Canada's Strait of Georgia, the NEPTUNE offshore observatory spans the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate — bounded to the East by the North American plate in the Pacific Northwest, and to the West by the Pacific plate — and an Arctic Ocean miniobservatory sits in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. [Ocean Sounds: The 8 Weirdest Noises of the Antarctic]

The NEPTUNE observatory has research stations, or nodes, on the continental shelf, the continental slope, in the middle of the plate and at a midocean ridge. Each node is outfitted with underwater microphones, or hydrophones.

"If you want to study what's going on in the ocean, the best tool by far is sound," said Tom Dakin, an acoustic specialist at ONC's sensors technology development office.

Listening to the ocean

Sound travels much farther in the ocean than other forms of energy — low-frequency sound can penetrate more than 600 miles (thousands of kilometers) deep, Dakin told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ONC uses sound in its studies in two ways: passively or actively. Passive acoustic monitoring is exactly what it sounds like — listening to the ambient noises of the ocean. Active acoustics involves emitting sounds and measuring how those noises interact with the ocean.

"There are all kinds of sounds being made in the ocean, and they all have a telltale signature," Dakin said.

The organization makes these recordings publically available online. But in addition to sounds made by marine animals, geological events or weather conditions, ONC's hydrophones also pick up the movements of submarines — information the U.S. Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy don't really want broadcast to the outside world. The navies handle this by filtering the data and redacting sensitive information to protect national security, The Atlantic reported.

But that article may have been a little misleading, Dakin said. It's true the hydrophone recordings get diverted through a military computer, where officials filter data in the range of frequencies produced by their vessels and chop out the sensitive parts. But, ONC only loses a small fraction of its data (about 4 percent), and whatever isn't sent through immediately gets returned in less than a week, Dakin said. "At end of the day, we hardly miss any data at all," he said.

Whale conversations

Marine biologists use ONC's hydrophones to eavesdrop on whales and other marine mammals that depend on sound to communicate in the ocean. For instance, toothed whales such as killer whales use echolocation to hunt and find prey, even in pitch-black water. But noise from shipping activities in the ocean is increasing, posing a threat to these animals' way of life. [Gallery: Creatures from the Census of Marine Life]

"If you start putting in a bunch of external man-made noise, [whales] are going to have a hard time communicating," Dakin said. It's like trying to have a conversation with somebody at a rock concert, he said — you have to shout, you can't hold a conversation for very long and you wouldn’t be able to detect different inflections that you would normally be able to hear.

Dakin has been diving when a big ship has gone by, and "it feels like somebody's whacking you in the chest with a two-by-four," he said.

ONC's hydrophone network monitors background ocean noise to understand how it impacts many of these whale populations.

Ears on the Earth

Acoustic instruments are already widely used to monitor geological activity. The hydrophones at the midocean ridge monitor volcanic activity, listening to the gurgles of underwater eruptions.

Hydrophones can also detect earthquakes by sensing pressure waves in the water, although seismometers, which measure pressure waves in the seafloor, are the primary devices used for earthquake monitoring.

Another way hydrophones can be used includes measuring the temperature of the ocean, through a technique called acoustic thermometry. It's a useful way to measure global warming, Dakin said, "because most of the heat we generate goes into the ocean."

He explained that temperature and pressure differences in the ocean affect the speed of sound. These conditions produce a region in the ocean known as the deep sound channel, where sound travels slower than in the water above and below it. Sounds in the ocean always get bent back to the deep sound channel, so if you can tell the angle and depth of the sounds, you can measure their travel time and use it to calculate the ocean temperature.

In addition to all the known sounds in the ocean, there are many noises that still mystify scientists, Dakin said. "We're getting to the point now where we're trying to map out all of these things."

Listen to more underwater sounds from Ocean Networks Canada here.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 3:59 p.m. ET August 26. Hydrophones are used in acoustic thermometry, but not by Ocean Networks Canada.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus