In Photos: Stunning Views of Titan from Cassini

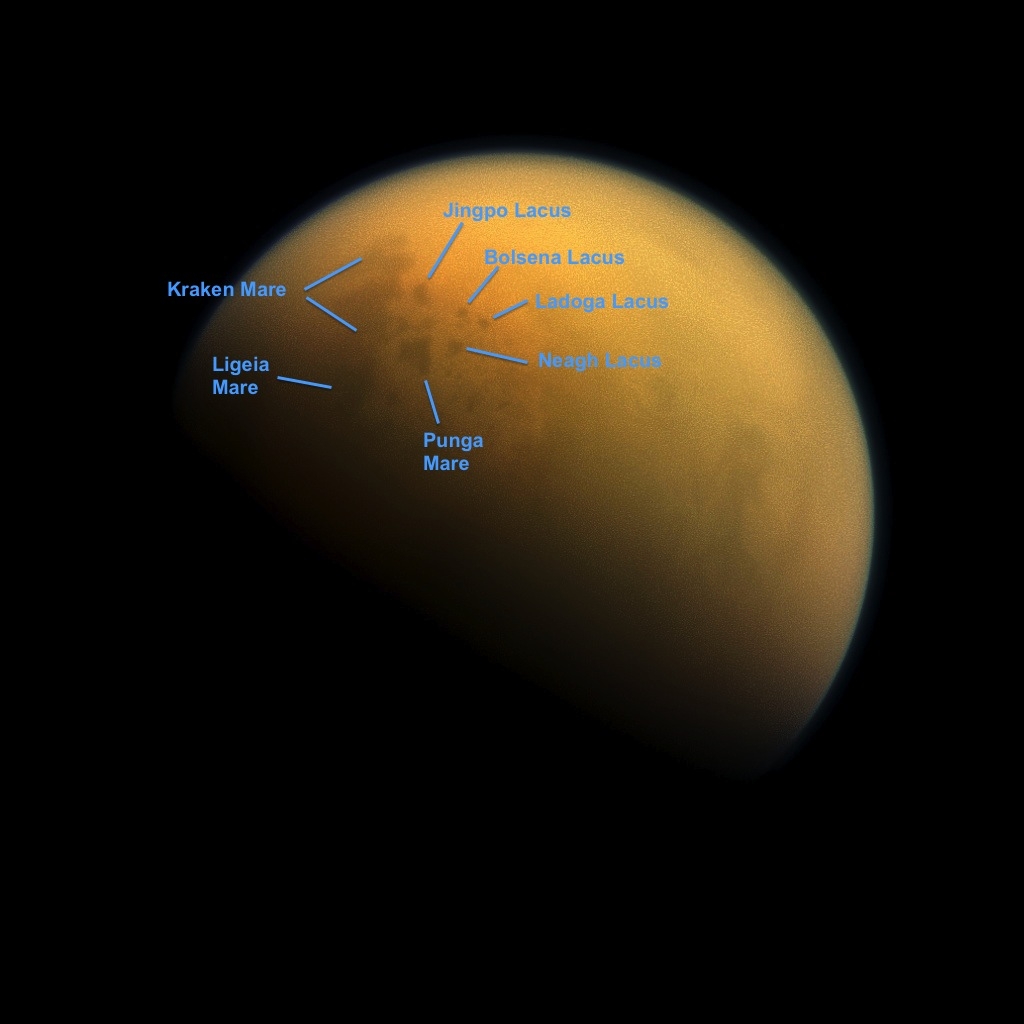

Titan

Peering through Titan's hazy atmosphere, a high-resolution camera aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft revealed Saturn moon's largest seas, the largest of which is Kraken Mare, and hydrocarbon lakes. Titan stands out as the only place in the solar system, besides Earth, to support stable liquids on its surface; its lakes are made of liquid ethane and methane.

The image, taken on Oct. 7, 2013, was snapped at a distance of about 809,000 miles (1.303 million kilometers) from Titan.

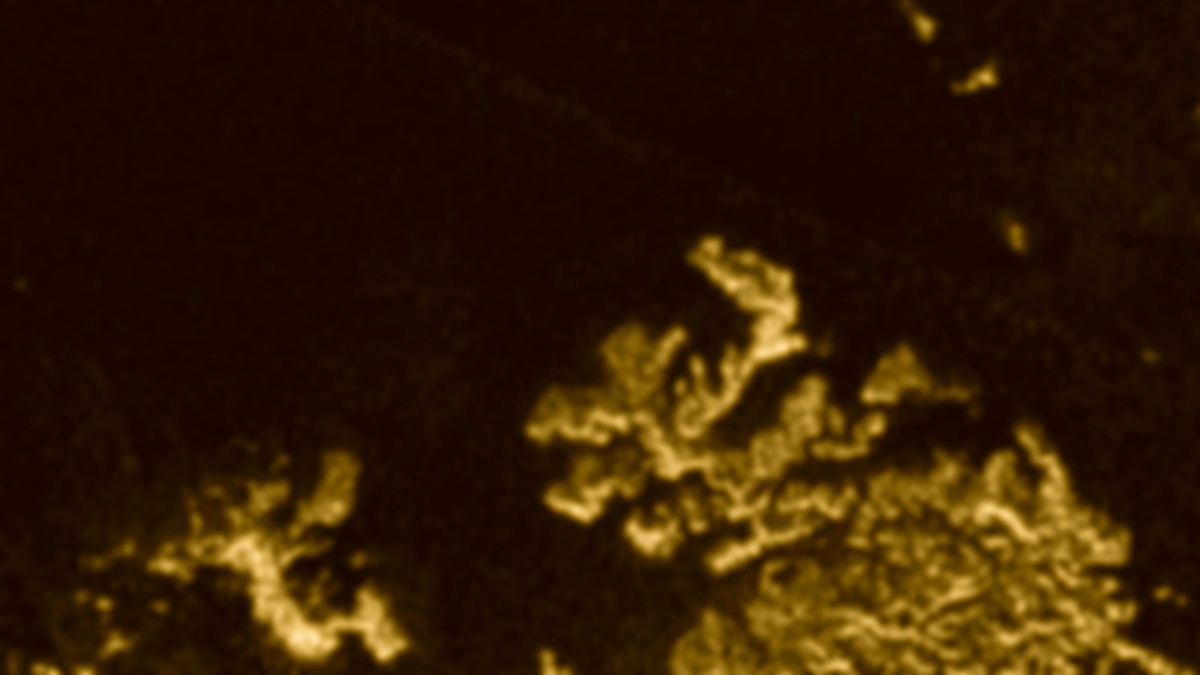

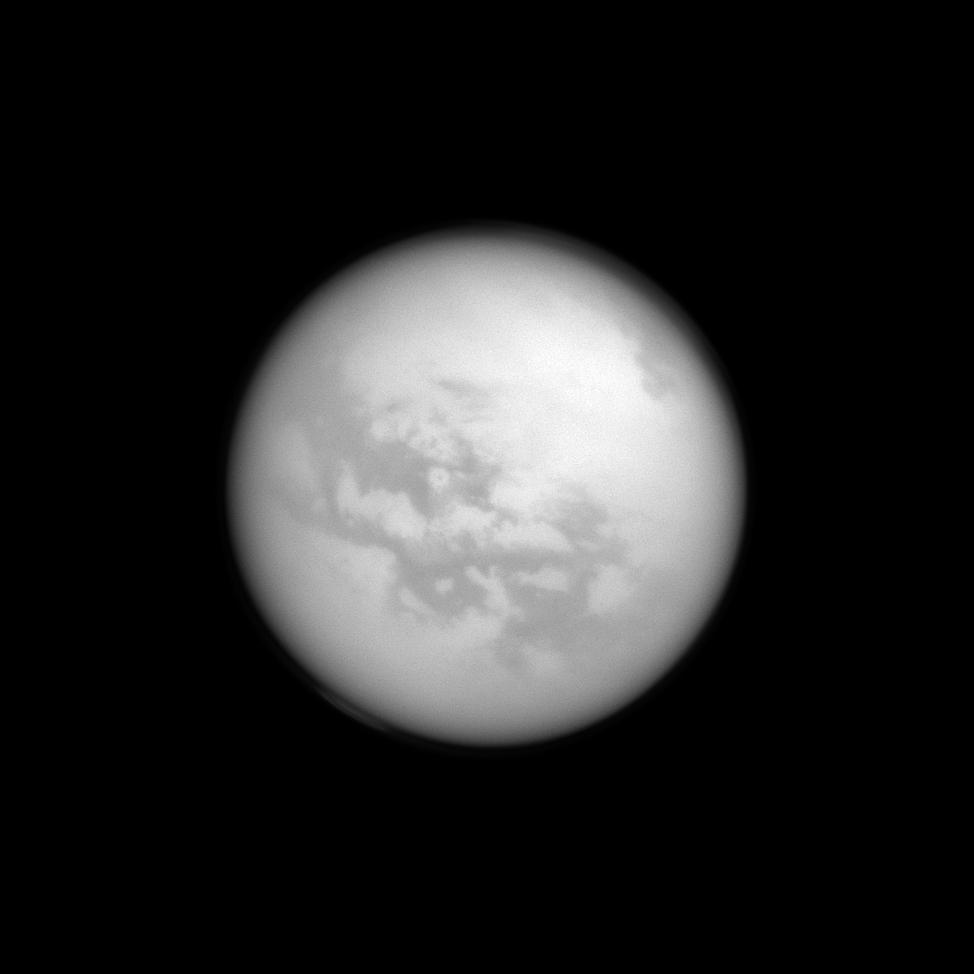

Northern Seas

The northern seas on Saturn’s largest moon Titan could be experiencing seasonal phenomena similar to those found in Earth's lakes, such as waves and bubbles, suggests a study detailed June 22, 2014, in the journal Nature Geoscience.

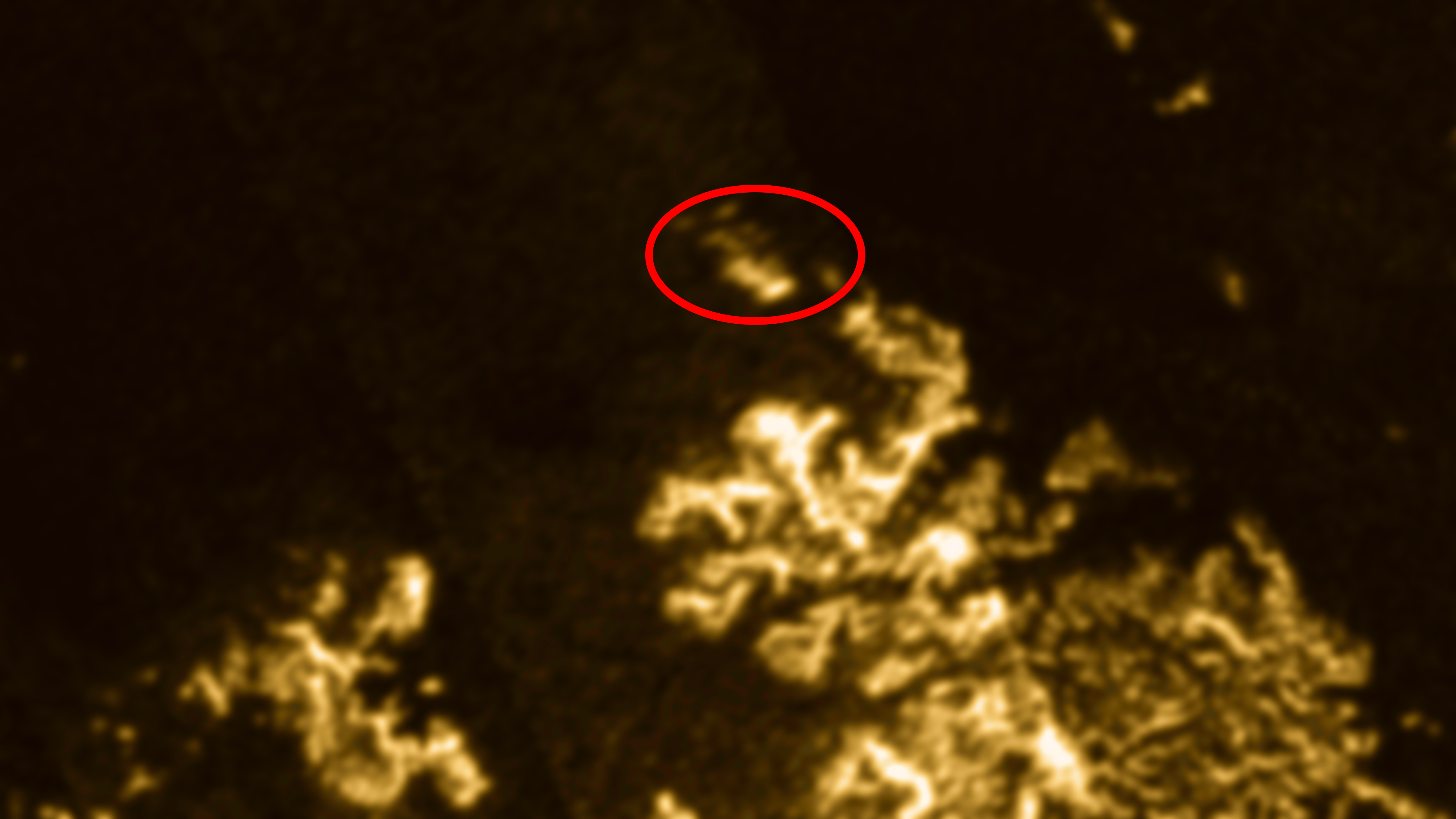

Bright spots

Transient features, shown has bright spots, in the hydrocarbon lake Ligeia Mare on Saturn's largest moon Titan may be waves or bubbles (circled in red). This image was acquired by the Cassini RADAR system on July 10, 2013.

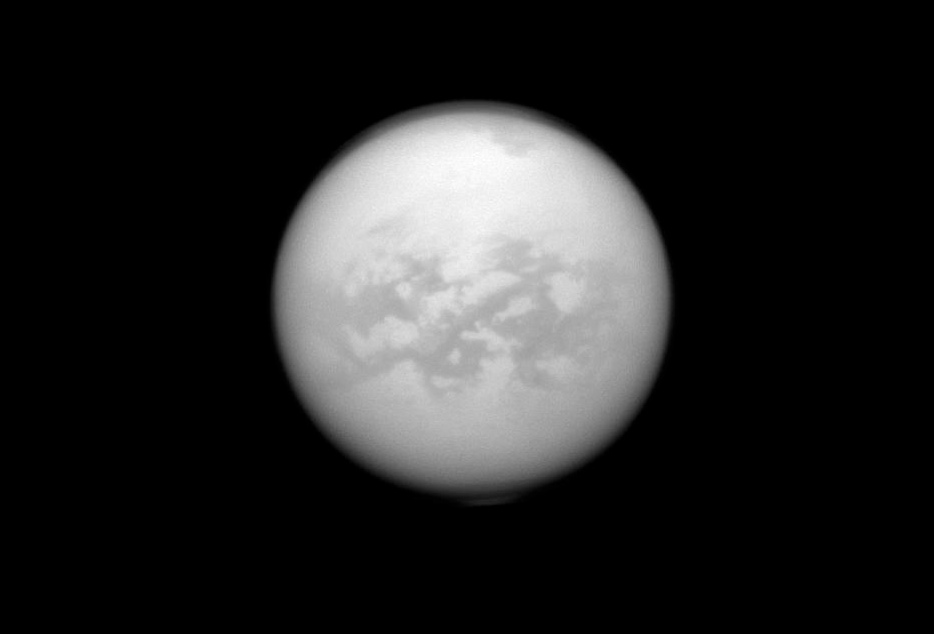

Senkyo

Donning its infrared "glasses," a narrow-angle camera aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft peers through the haze to reveal Titan's equatorial region dubbed "Senkyo." Scientists suspect the dark features represent expansive dunes of hydrocarbon particles that dropped out of Titan's atmosphere.

At some 3,200 miles (5,150 km) across, Titan is Saturn's largest moon.

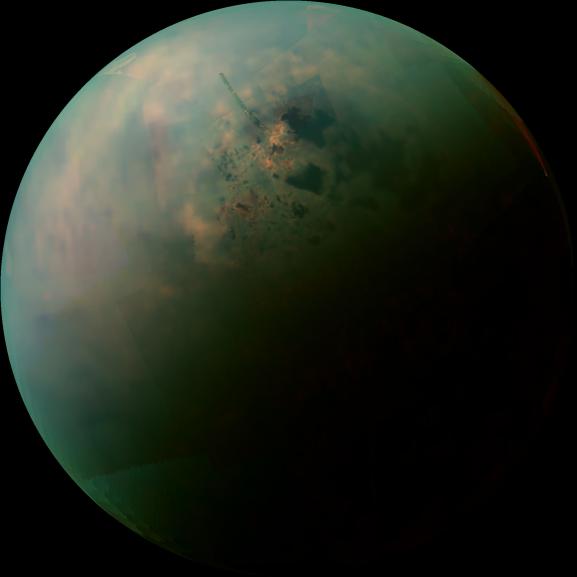

Hydrocarbon lakes

Infrared data collected by Cassini was used to piece together this false-color mosaic of Titan, highlighting the surface materials around the moon's hydrocarbon lakes. Nearly all of these lakes, made of liquid ethane and methane, are located near Titan's north pole.

Titan's largest sea, Kraken Mare spreads out in branches in the upper-right portion of the image. Kraken Mare covers an area about the size of Earth's Caspian Sea and Lake Superior combined. The second-largest Titan Sea, Ligeia is the dark zone up and to the left of Kraken Mare, while Punga Mare, the third largest sea, is the structure shaped like a sports fan's foam finger (pointing just up from left). The image was taken on Sept. 12, 2013.

Fensai and Aztlan

Thanks to its near-infrared filters, a narrow-angle camera aboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft could capture dark features thought to be vast dunes of hydrocarbon particles that dropped out from Titan's atmosphere. The features have been dubbed "Fensal" and "Aztlan" by scientists. The image was taken on April 13, 2013.

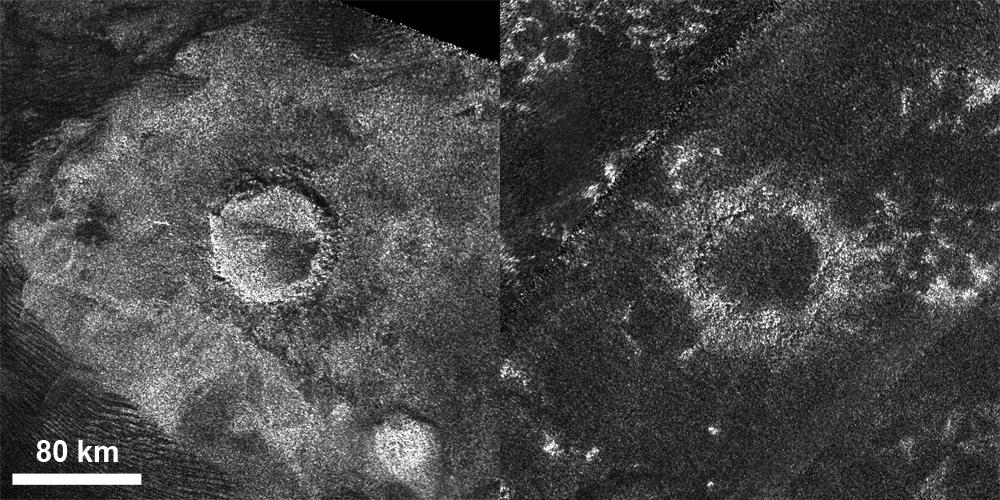

Titan craters

A relatively "fresh" crater called Sinlap (left) and a very degraded crater called Soi (right) were captured in this set of images acquired by Cassini's radar instrument on Feb. 15, 2005 (Sinlap), and May 21, 2009 and July 22, 2006 (mosaic showing Soi). Both craters are 50 miles (80 km) across.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

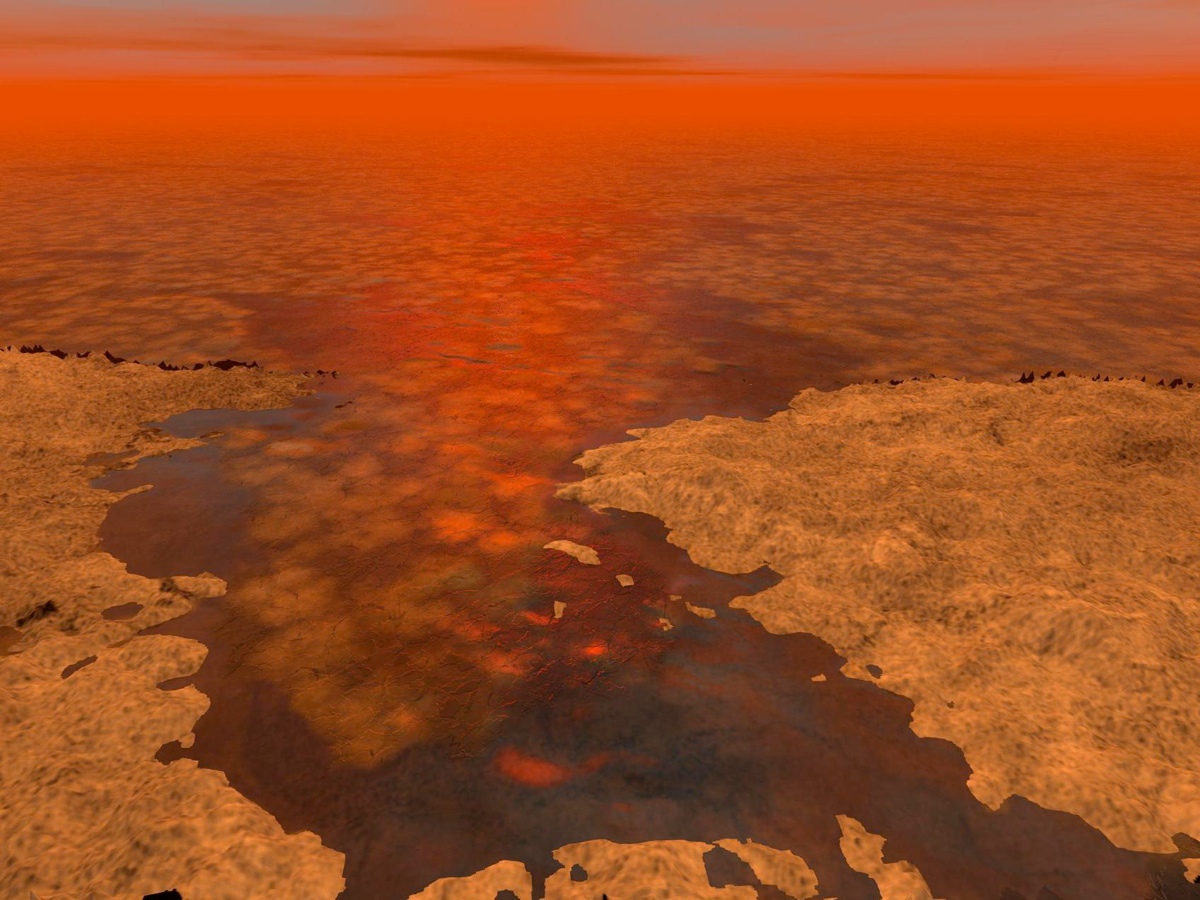

Floating ice

: Clumps of hydrocarbon ice (made of ethane and methane) may be floating on Titan's liquid hydrocarbon seas, according to a model from scientists working on NASA's Cassini mission. Here's an artist's vision of what that floating ice might look like, shown as lighter-colored clusters.

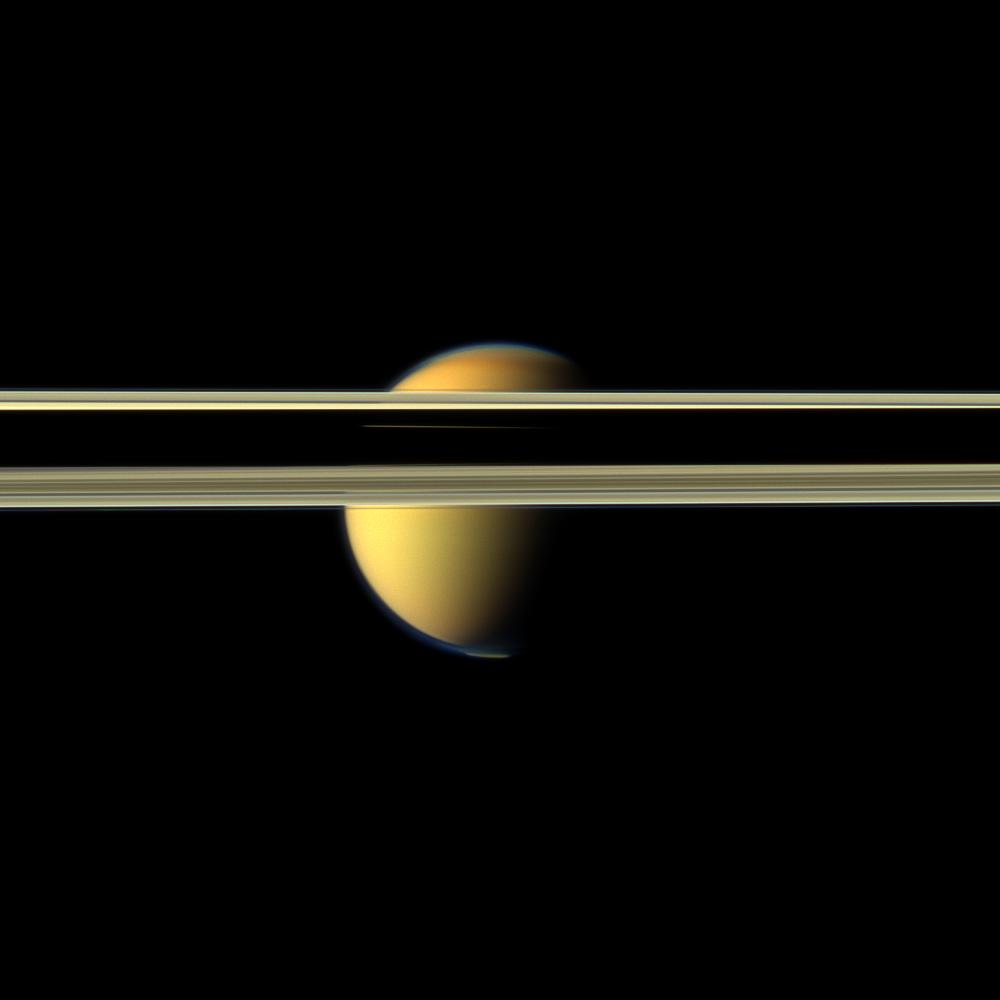

Obscured by rings

Wow! NASA's Cassini spacecraft gets a view of Titan obscured by Saturn's rings. A shadow cast by the planet makes parts of the rings near the center of the image appear dark. The image, snapped on May 16, 2012, looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings, from just above the ring plane.

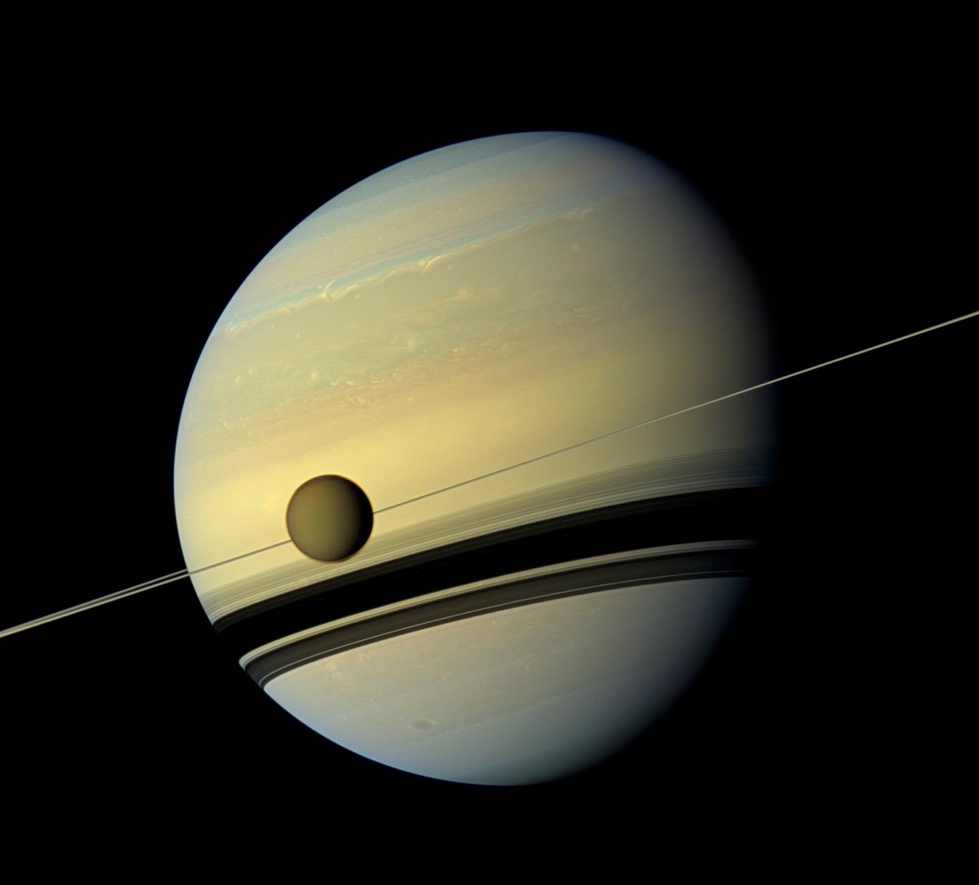

Dangling moon

Big Titan, which is larger than the planet Mercury, appears to dangle in front of its parent planet Saturn in this image looking toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings, from just above the ring plane. Cassini's wide-angle camera captured this mosaic of six images — two each of red, green and blue spectral filters — on May 16, 2012 from about 483,000 miles (778,000 kilometers) from Titan.

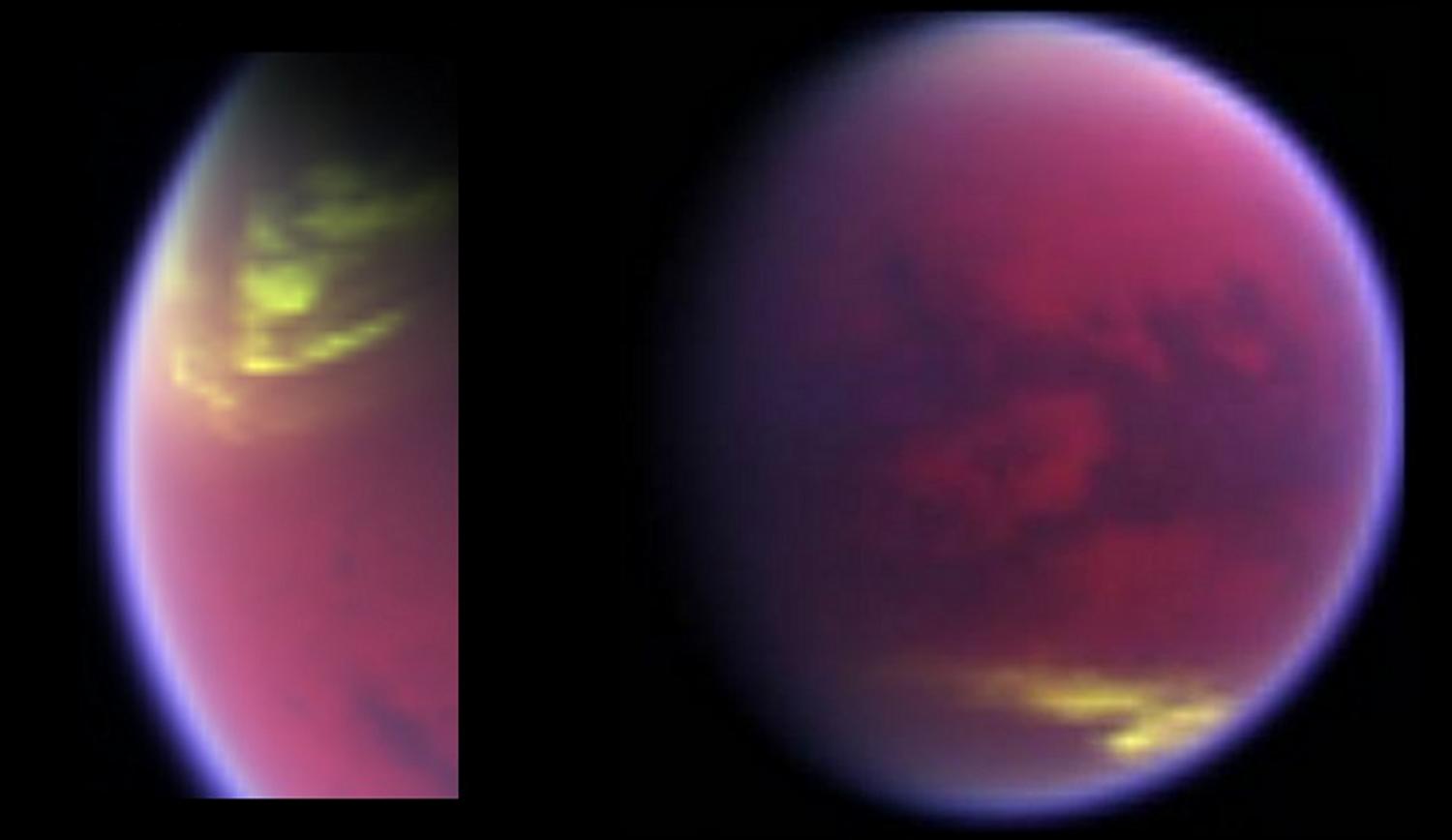

Clouds of Titan

Data from NASA's Cassini spacecraft was used to create this pair of false-color images showing clouds covering parts of Titan, with cloud cover appearing yellow and the moon's hazy atmosphere showing itself in magenta. Cloud cover can be seen dissolving from Titan's north polar region between May 12, 2008 (left) and Dec. 12, 2009 (right).

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.