Why Spider Fangs Are Nature's Perfect Needles

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

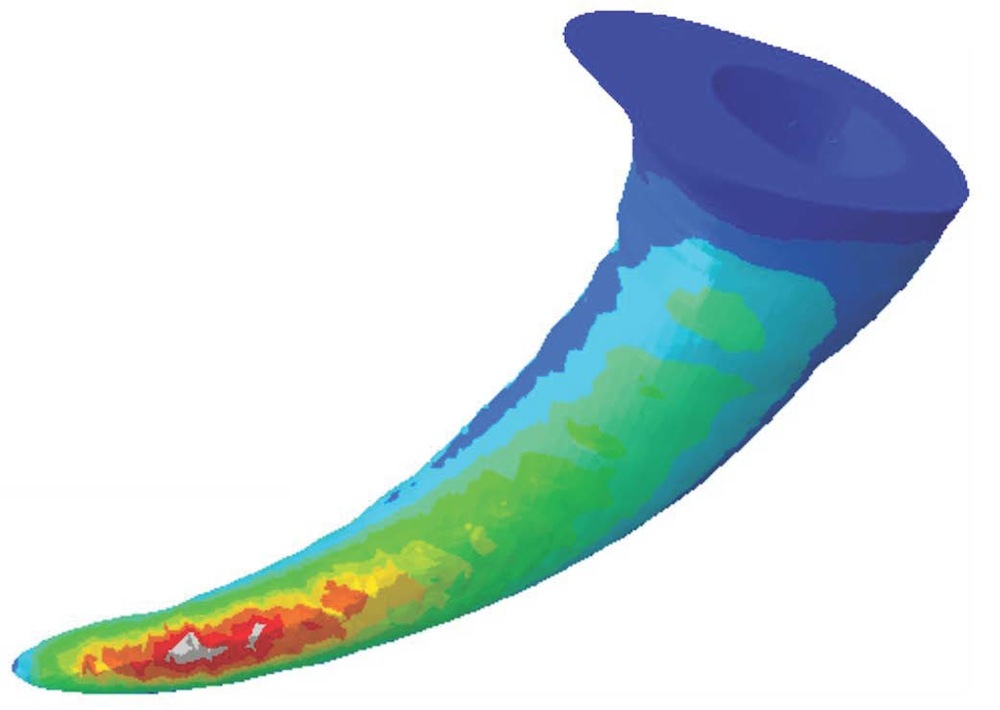

A spider's fangs are natural injection needles, making them perfectly suited for piercing the skeletons of prey and delivering a kiss of venom, a new study finds.

The toothy barbs of a large wandering spider are curved in order to hold the spider's prey in place, and their conical shape helps them resist deformation. Understanding the biomechanics of spider fangs could inspire new medical injection devices, researchers say.

"For biomedical applications, for example, the spider fang may lead to the design of new infusion techniques, new blood-bypassing instruments and many other life-saving technologies," said Benny Bar-On, a biomaterials scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces in Germany and co-author of the study published today (May 27) in the journal Nature Communications. [Gallery: Spooky Spiders]

Spider fangs have evolved to penetrate the external skeleton of the arachnids' prey, usually insects, in order to inject venom, the researchers said. As such, the fangs have to be able to withstand significant forces without deforming or breaking.

In this study, Bar-On and his colleagues investigated the structural mechanics of the wandering spider Cupiennius salei, which is mostly found in Central America. Wandering spiders don't build a web to catch their prey; instead, they hunt around on the ground.

The researchers chose C. salei because it's easy to breed this species in large numbers year round in the laboratory. They modeled its fangs structurally in experiments and in simulations.

Unlike other biological injection needles, such as mosquito and bee stingers, the fangs of these spiders are curved. The curvature enables the arachnids to attack from different directions and hold their prey in place as they inject their venom, the researchers found.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The hollow, conical shape of the spiders' fangs gives them nearly optimal stiffness per unit volume — a measure of their resistance to deformation — making them ideally suited for piercing prey.

The fangs are a composite of protein and chitin, a carbohydrate molecule found in the shells of many insects and crustaceans, whose microscopic structure is well suited for its purpose, the results suggest.

Understanding the biomechanics of spider fangs could reveal how other sharp structures, from a scorpion's stinger to a mammoth's tusk, evolved in nature, the researchers said. Furthermore, the fangs' design might inspire scientists to develop better injection needles and other medical devices.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing spider photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus