Bay Area's Future Earthquakes: Knockout Blow, or Combination Punch?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

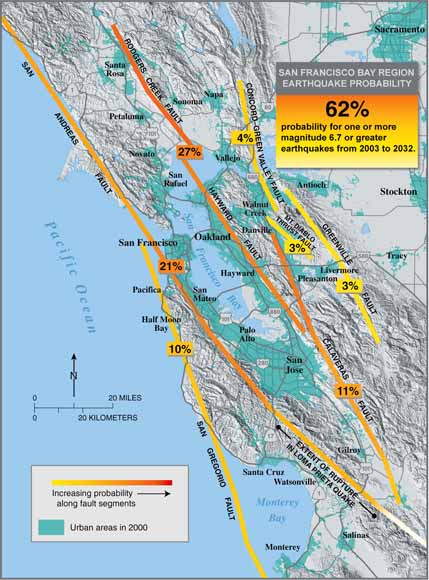

California's San Francisco Bay Area grew into a metropolis during the eerily quiet earthquake gap following its devastating 1906 temblor. Scientists predict a 63 percent chance of another big quake before 2032, but when the shaking starts, it may not be a single "Big One" as in 1906, according to a new study.

Instead, the Bay Area could face a cluster of deadly earthquakes that deliver a series of rapid punches, researchers report today (May 19) in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

The report is another nail in the coffin for the idea that earthquake faults repeat their behaviors in the same way every time. "The historical record is not sacrosanct," said lead study author David Schwartz, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). "It's really clear that the frequency of different earthquake sizes varies over time."

Schwartz and his co-authors have pieced together a detailed record of Bay earthquakes back to 1600. The bygone earthquakes come from several sources, such as paleoseismology (digging up evidence of shaking), and historic records from Spanish missions.

Between 1690 and 1776, the Bay Area's most dangerous faults unleashed a series of earthquakes between magnitude 6.6 and 7.8, Schwartz and his co-authors report. (The 1906 San Francisco quake was probably a magnitude 7.9, using modern estimates.) These include the Hayward fault, the San Andreas Fault, the northern Calaveras fault, the Rodgers Creek fault and the San Gregorio fault. [In Photos: The Great San Francisco Earthquake]

An earthquake lull followed this quake cluster, though it was not as quiet in the Bay Area as post-1906, the study reports. Then the 1906 earthquake struck, and a life free from big earthquakes returned again.

Schwartz (and the USGS) thinks it won't be long before San Francisco starts to shake again. The big question is whether it will be the feared "Big One" or a cluster of earthquakes, and which would be worst.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We haven't had to face a series of relatively closely timed earthquakes in a modern, urban city," Schwartz said. "It would be bad news."

Forecasts unchanged

However, the discovery doesn't immediately change the USGS official earthquake forecast for the Bay Area, which projects a 62 percent chance of a magnitude-6.7 earthquake by 2032, Schwartz said.

New probability forecasts for the region, currently in development, also take into account the possibility of scenarios outside the massive San Andreas Fault quake, such as several faults rupturing at once, said Tom Parsons, a USGS research seismologist who was not involved in the study.

"I think that 1906 is only one of many different options," Parsons said. "We don't know what's going to happen next, but this study provides an answer and it's also broadening our uncertainty."

Schwartz thinks the earthquake cycles suggest these Bay Area faults need to build up a critical stress level before they begin to break. "It takes a while for the crust to reload," he said.

The bad news? The Earth's tectonic plates have probably shifted far enough since 1906 to reach that threshold, he said.

The Bay Area sprawls across the boundary of two massive tectonic plates. The North America plate is sliding south relative to the Pacific plate at about 2 inches (5 centimeters) per year. The plates build up friction that is released as earthquakes. Most of the stress is relieved on the San Andreas Fault, but a zone of faults about 125 miles (200 kilometers) wide lets off the rest.

"Maybe the next sequence won't be exactly the same, but we really could have a series of earthquakes on all or most of these faults over a relatively short period of time," Schwartz said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus