See-Through Frog Embryos Know When Dad's Not Watching

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

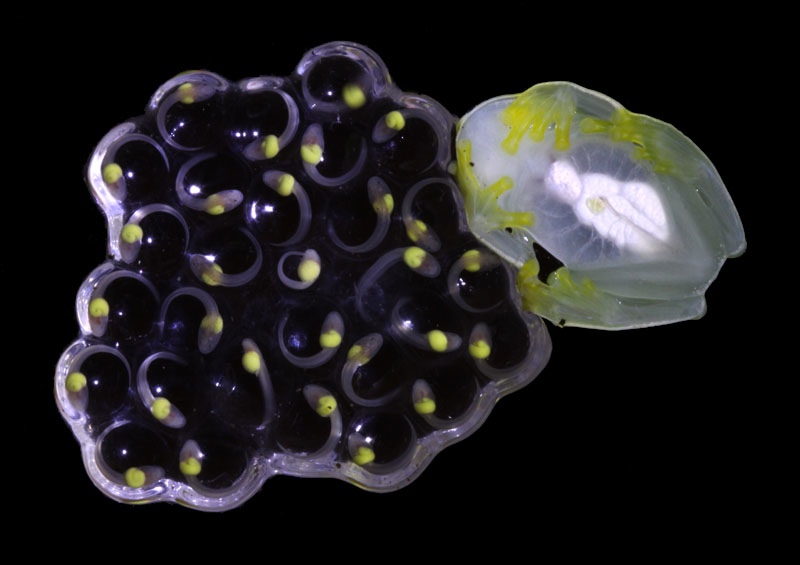

With their hearts, guts and other internal organs visible through translucent skin, glass frogs look vulnerable.

Now, scientists have found that the embryos of these nocturnal frogs do not like staying defenseless, so they hatch more quickly when their fathers desert them.

The early stages of life are usually the most vulnerable, and parents across many animal species protect their embryos as they develop. Birds typically brood their own eggs, resting on top of them for incubation, while humans and similar mammals protect embryos within themselves during pregnancy. There are exceptions to such rules — for instance, cuckoos get other birds to brood their eggs. [The 9 Most Devoted Dads of the Animal Kingdom]

However, many embryos have ways of taking care of themselves, especially if their parents abandon them. For instance, "in red-eyed tree frogs, a species without parental care, embryos can assess and rapidly hatch in response to predators," said lead study author Jesse Delia, an ethologist at Boston University. "Embryos are evolving, responsive organisms."

Although scientists have found that embryos can hatch early in species without parental care, Delia told Live Science, "to date, no work has evaluated whether embryos hatch in response to bad parents" — that is, parents that shirk their duties in species that are supposed to care for their eggs.

To explore how embryos might respond to bad parenting, scientists investigated glass frogs, amphibians found throughout Latin America. In the species Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni, the fathers brood eggs to keep them wet for three to 19 days after the mothers lay the eggs. The eggs can hatch anywhere from 12 to 27 days after they are laid.

"In glass frogs, fathers provide parental care to embryos, and there is a lot of variation among fathers — some provide care for prolonged periods, while others seem to provide the bare minimum needed for embryos to survive," Delia said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In glass frogs, fathers can desert their eggs for up to two days in order to pursue sex. This leaves their eggs vulnerable to dehydration and death.

In experiments conducted out in the field in Mexico in 2009 and 2010, scientists removed 40 males from eggs two to eight days after the eggs were laid, and monitored embryo responses.

"Field work was challenging at times — the behavior of these frogs is truly fascinating, but the only way to study these nocturnal beasts is by becoming a creature of the night," Delia said. "I conducted research in a small pueblo in the Sierra Madre del Sur of Oaxaca. Pueblo life typically starts at 4 to 5 a.m., often initiated by roosters and dogs, then followed by wake-up music to get the day going. My night typically ended at 4 a.m., so getting sleep was tricky at times.

"Also, 2010 was one of the wettest years on record for southern Mexico," Delia said. "Collecting data required that I was on stream taking measurements each night, regardless of weather."

The scientists discovered that glass-frog eggs hatched about 21 percent earlier on average when the fathers were removed. They hatched up to about 34 percent earlier when conditions were drier, suggesting that dehydration was the cue the eggs relied on to hatch early.

"Embryos can cope with delinquent dads," Delia said.

The researchers suggest this kind of embryo behavior may be common among species that provide care to eggs, such as insects, bony fishes and amphibians. "Variation in parental care seems to be the norm rather than the exception," Delia said.

The scientists detailed their findings online April 30 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus