New Maps Show Seismic Vulnerabilities of Eastern US

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

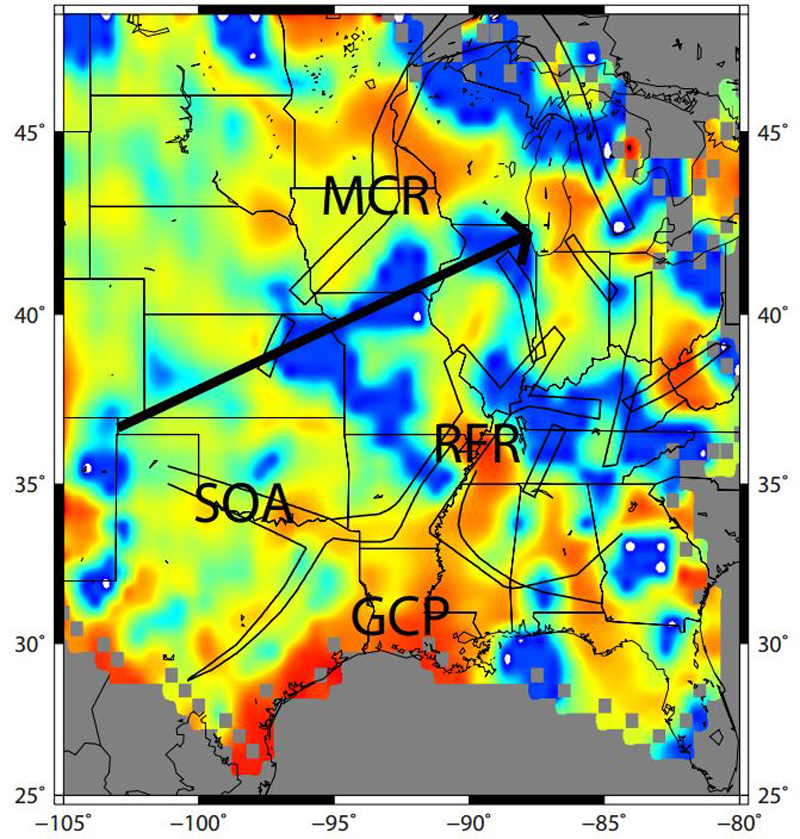

New seismic maps of the central and eastern United States may help improve earthquake hazard assessments by identifying regions where seismic shock waves can travel the fastest and farthest from earthquake epicenters, according to a recent report.

When an earthquake strikes, the shock waves it generates pulse through the Earth's crust, traveling as far as 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) laterally before dissipating. The distance and force with which a shock wave travels depends on a variety of factors, including the strength of the earthquake and the composition of the surrounding crust (the uppermost layer of the planet). For example, shock waves may only travel several hundred miles through warm, tectonically active regions of the crust but may travel much farther in colder, inactive regions. [The 10 Biggest Earthquakes in History]

"Cold rock is very stable and solid, and waves like to travel through stable things," said Andrea Gallegos, a graduate student at New Mexico State University. "Hot things have a lot of random motion, and that slows down wave propagation."

Gallegos has worked with colleagues to analyze seismic data and create maps that illustrate seismic attenuation — the loss of intensity as shock waves get absorbed by the crust — across the central and eastern United States, in hopes of helping to improve seismic risk assessments within those regions.

The maps show that the most vulnerable regions surround the New Madrid Seismic Zone in New Madrid, Mo., where a series of damaging earthquakes occurred in 1811 and 1812.

Other areas with crustal conditions that allow shock waves to quickly pass through without dissipating much include central Georgia, Tennessee and Michigan. Texas, Louisiana and Alabama, on the other hand, appear less vulnerable.

"If you're in Louisiana and you get an earthquake from Oklahoma, that wave is probably going to die out within a couple of hundred kilometers, because the sediment is going to cause the wave to die out quickly," Gallegos told Live Science. "But if you go to Iowa or the Midwest, you are going to see that wave last for closer to 1,000 kilometers [about 600 miles]."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the central and eastern United States may not experience earthquakes as frequently as the western United States does, those regions are not immune to temblors. An active fault zone in South Carolina resulted in a magnitude-4.1 earthquake on Feb. 15, and another active fault zone in Ottawa, Canada, poses a threat to states in the northeastern part of the United States. Other fault zones are scattered throughout the interior of the country and, in some ways, pose larger risks than the West Coast fault zones because communities in the eastern part of the country are generally less prepared for these threats, Gallegos said.

The team now plans to expand their methods to create a map that spans the entire country. Ultimately, they hope to share their data with seismic hazard teams at the U.S. Geological Survey or elsewhere to help update seismic hazard maps.

The study findings were detailed last month in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus