'Dead Priest's Hair'? Alternative Medicine Poisoned Man

A man in Switzerland developed severe lead poisoning after undergoing an alternative medicine treatment — he took pills that he thought contained the hair of a dead Bhutanese priest, but the pills were actually replete with the toxic metal lead, according to a report of his case.

It took the man's doctors a week to find out that their patient was taking these pills, and that his symptoms were signs of lead poisoning. (In developed countries, lead poisoning is rare because lead levels in the environment are controlled.)

"It was a very difficult case. The patient had unspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, confusion, constipation, vomiting," said Dr. Omar Kherad, a physician at the Hôpital de la Tour in Geneva.

"We did all the normal tests — in this case, gastroscopy, CT scan, all the blood tests," Kherad said. "We did not find anything, initially."

The doctors finally asked the patient whether he was taking any traditional remedies, because although he lived in Switzerland, he frequently traveled to Bhutan, where people often use alternative medicine.

The doctors were "very surprised when he finally revealed he was taking these pellets every day for three or four months," Kherad told LiveScience. [14 Oddest Medical Cases]

The doctors then checked the level of lead in the patient's blood, and found it to be at least 100 times higher than what is normally found in people living in Switzerland.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

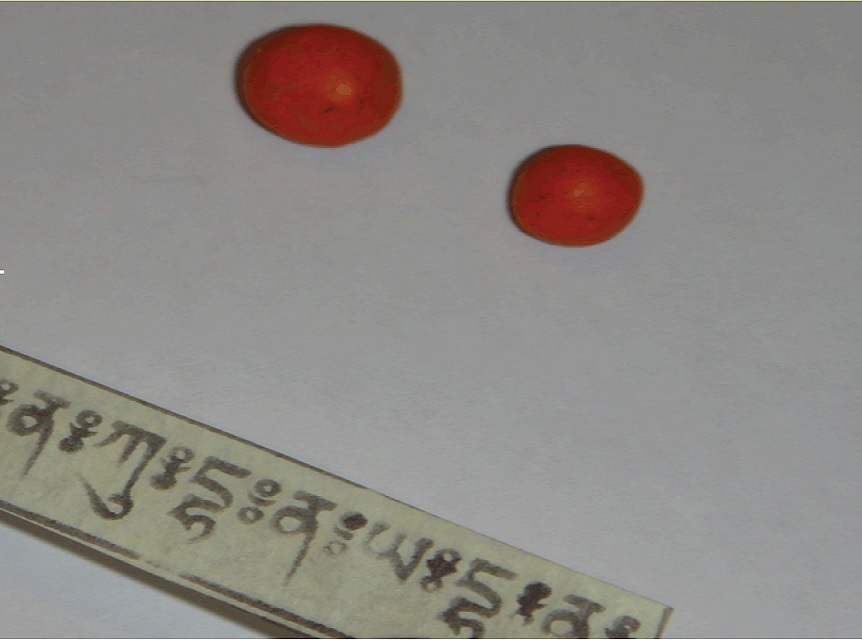

The laboratory tests on the pellets found high levels of lead in the red paint on the pellets, corroborating doctors' guess that the pellets were the source of lead in the man's body. [Image of the pellets]

The doctors who treated the man warned that although lead is no longer widely used in Western countries, physicians should ask their patients whether they are taking alternative medications from countries where high levels of lead can still be found in materials such as paint.

"As a consequence of general globalization in medicine, complementary and alternative medicines are being increasingly used in Western countries as they become more popular and easily available on the Internet," the doctors wrote in their report, published last month in the online journal F1000research.

Articles in F1000research are not peer-reviewed before they are published, but experts can review and comment on an article post-publication.

Dr. Arnaud Perrier, a physician at the University Hospitals of Geneva who wasn't involved with the case, said many doctors may not be aware that alternative medicine is frequently a source of lead poisoning.

The doctors' conclusion that physicians should ask patients about their history of using such medications is important and sound advice, Perrier said.

The doctors who treated the man informed Bhutan's health minister about the case, and the minister intervened to inform the population of the capital of Bhutan to be very careful if they are taking alternative medicine, Kherad said.

The man said he was taking the pellets to treat another condition he had in the past, Bell's palsy, a form of facial paralysis that is sometimes treated with anti-inflammatory medications, and usually resolves on its own.

"The patient was told the pellets contained hair of a deceased local priest," and would cure his condition," Kherad said. "When we did an analysis, we didn't find any hair in the pellets."

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.