Fossil of Largest Platypus Discovered in Australia

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

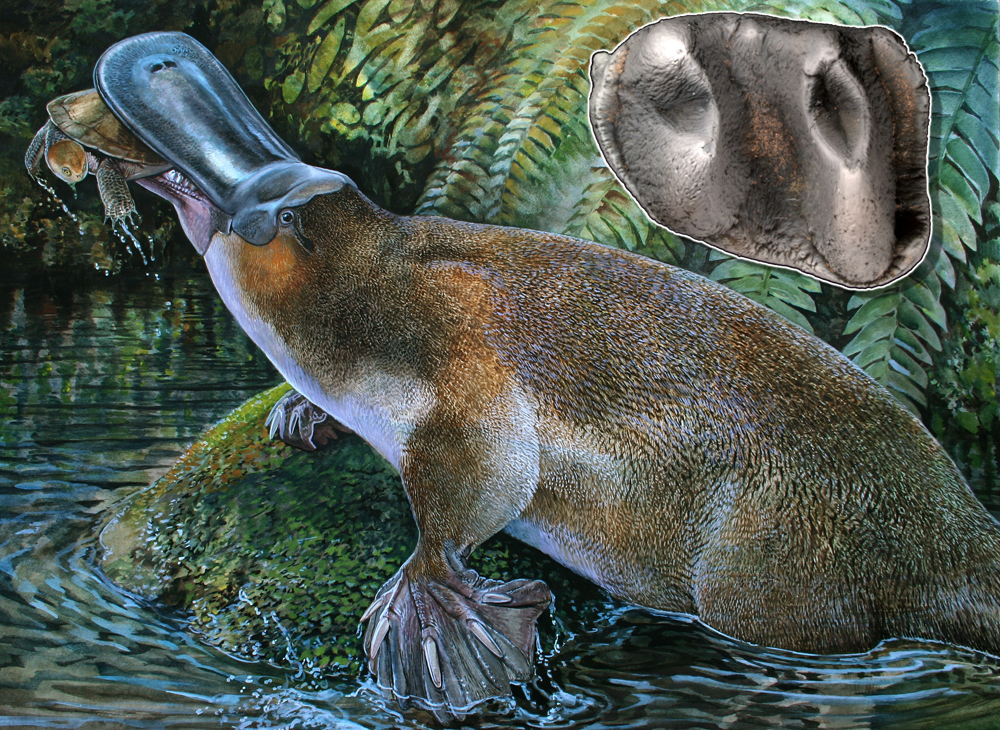

About the size of a child, the largest-known platypus roamed what is now Australia as far back as 15 million years ago, according to newfound fossil remains of the giant monotreme.

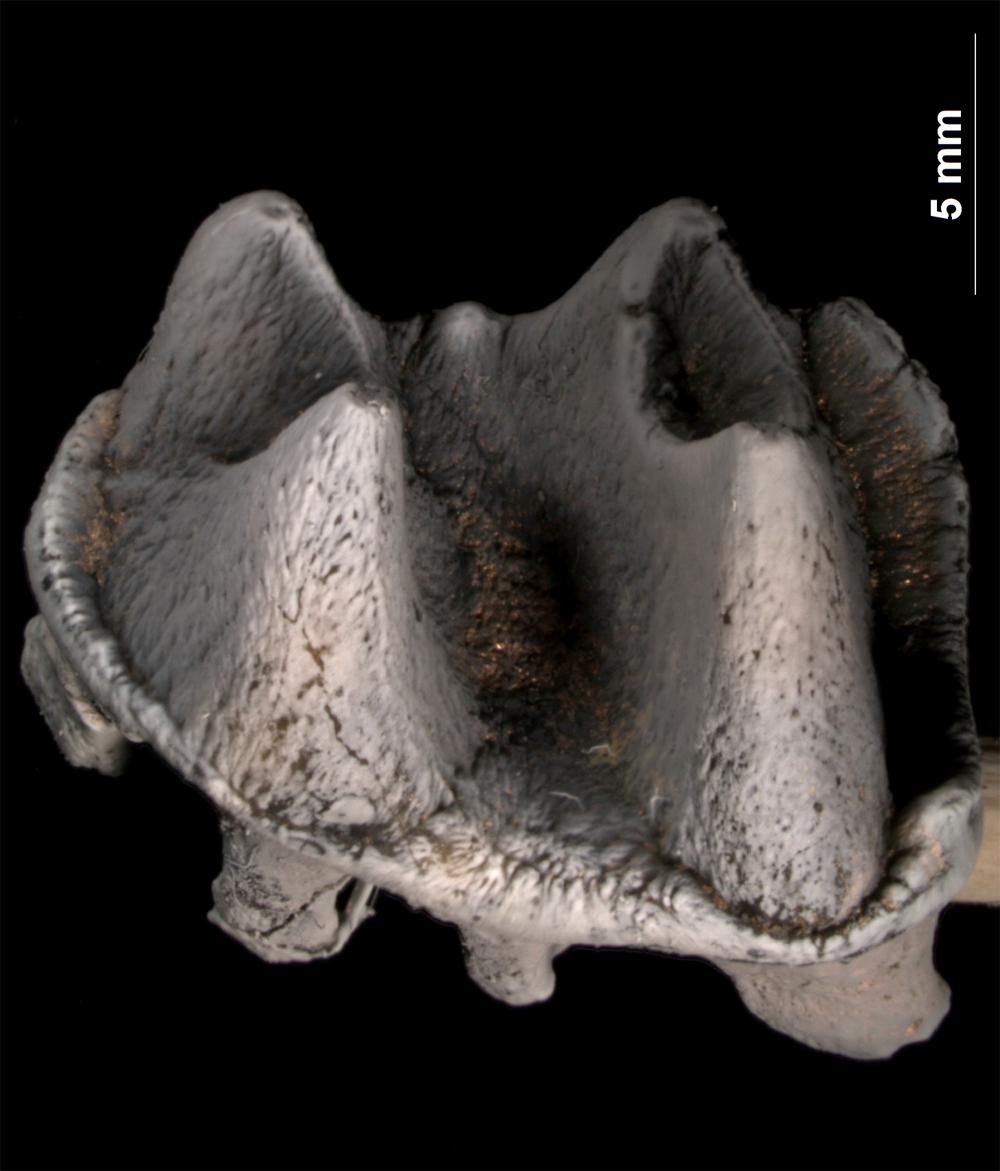

A team of paleontologists from the University of New South Wales in Australia identified the new species, called Obdurodon tharalkooschild, based on a single molar they discovered in the Riversleigh fossil field in northwestern Queensland, Australia. From measurements of the molar, the scientists have estimated the animal grew to be about 1 meter long (3.3 feet), which is twice the size of a modern platypus, and larger than the previously largest-known platypus ancestor, Obdurdon dicksoni.

Modern adult platypuses don't have teeth to compare the fossil to. But ancient platypuses, like O. dicksoni, did have teeth, and like many features of the platypus that set it apart from other mammals — such as its long bill, webbed feet and the fact that it lays eggs — platypus teeth are quite distinctive from all other mammal teeth, and are fairly easy to identify in the fossil record, study co-author Rebecca Pian, a graduate student at Columbia University, told LiveScience. [Images: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

"The overall shape of it, including the arrangement of the bumps on the top of the tooth, the way that those are arranged in a distinct shape, and the arrangement, shape and size of the roots are all distinctive," Pian said. "At least to somebody who knows what they are looking at."

The structure of the tooth suggests the animal was capable of eating not only the small insects and crayfish on which modern platypuses dine, but also small vertebrates such as certain fish and amphibians, and even small turtles, the team reports.

Based on the sedimentary rocks and other fossil assemblages surrounding the area where the tooth was found, the team has estimated that the animal lived between 5 million and 15 million years ago, though they still need to conduct further analyses to determine a more precise age.

Prior to this discovery, scientists had thought platypuses evolved fairly linearly, with only one species ever existing at any given time. But O. tharalkooschild appears to have coexisted with the slightly smaller O. dicksoni, suggesting the animal's evolutionary history is more complex than previously thought.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It means that there is lot that we still don't know," Pian said. "It's just highlighting how much we don't know about this very unique group of mammals, and how much there is still out there to learn about this group — where they came from, how they evolved, that kind of thing."

For now, the team has concluded their analyses of the tooth and will have to wait until they find more remains of the animal to conduct any follow-up work. Pian is optimistic that they will find something in the coming years, given the overall abundance of well-preserved fossils at the Riversleigh site.

The findings will be detailed next Tuesday (Nov. 12) in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow LiveScience on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus