Sipping Tarantula Venom Kills Crop-Eating Insects

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The venom in a tarantula's fangs packs a lethal punch when injected into its prey.

But the toxic brew could also serve as an insecticide against agricultural pests that consume the venom orally, a new study finds. A component of the spider venom is especially effective against the cotton bollworm, a pest that attacks crop plants.

Globally, insect agricultural pests reduce crop yields by 10 percent to 14 percent and damage 9 percent to 20 percent of stored food crops. Farmers primarily use chemical insecticides to control pests, but many insects are resistant to them.

In the last decade, researchers have been investigating "bioinsecticides," proteins derived from natural sources such as spider venom. [Photos: The World's Creepiest Spiders]

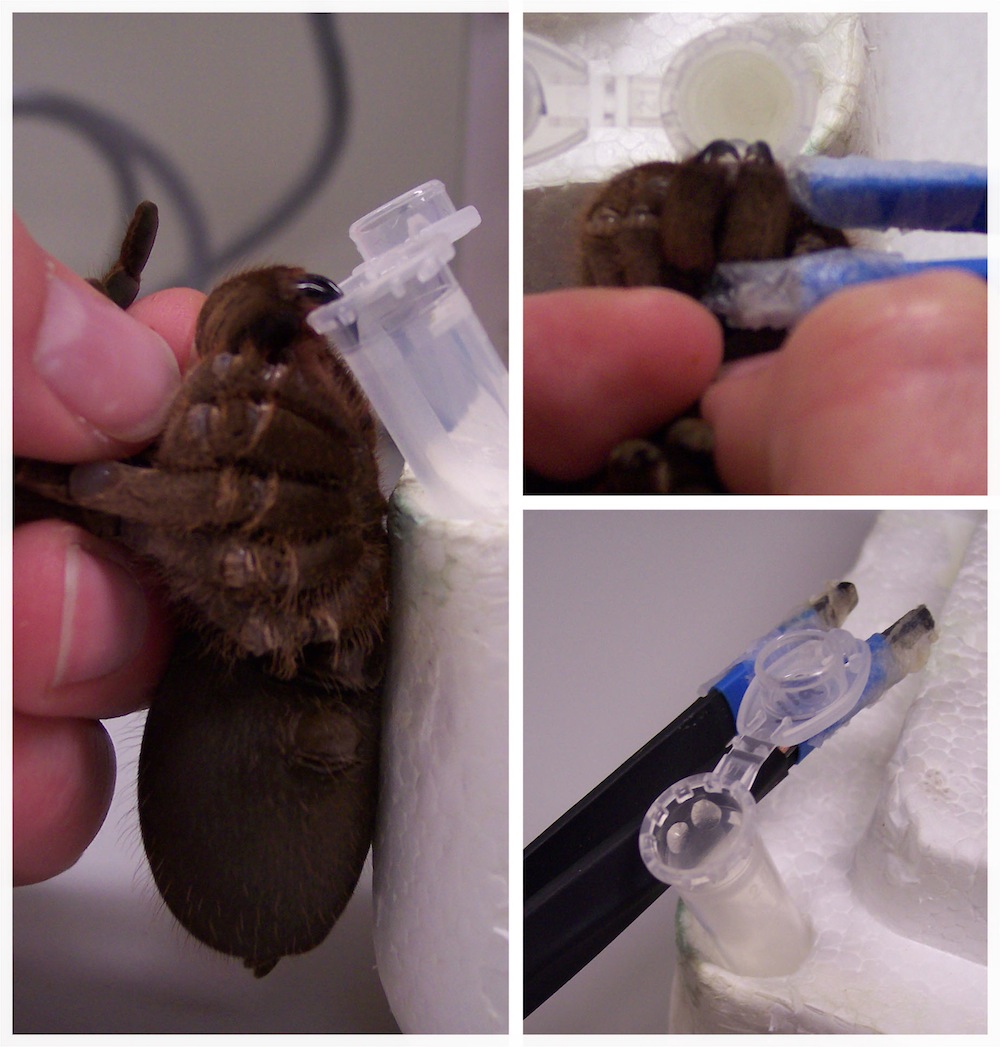

In the study, researchers milked venom from Australian tarantulas (Selenotypus plumipes), and isolated a small peptide — a molecular building block of cells — from the deadly substance. They fed the peptide to termites and cotton bollworms, and compared the effects with those of mealworms injected with the peptide.

When ingested by insects, the poisonous chemical, called orally active insecticidal peptide-1, was as toxic as the synthetic insecticide imidacloprid, the group reported today (Sept. 11) in the journal PLOS ONE. A combination of the venom peptide and synthetic insecticide was even more effective.

The venom was more potent against cotton bollworms than against termites and mealworms, which eat stored grains rather than crops, results showed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Venoms from other insect-eating animals, such as centipedes and scorpions, may also contain peptides that could be used as bioinsecticides. Or, scientists could genetically engineer insect-resistant plants or microbes that produce these toxins.

"The breakthrough discovery that spider toxins can have oral activity has implications not only for their use as bioinsecticides, but also for spider-venom peptides that are being considered for therapeutic use," study researcher Glenn King of the Institute for Molecular Bioscience at the University of Queensland, Australia, said in a statement.

S. plumipes is one of Australia's largest spiders, but is not harmful to humans.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus