'Grand Canyon' of Greenland Discovered Under Ice Sheet

The age of discovery isn't over yet. A colossal canyon, the longest on Earth, has just been found under Greenland's ice sheet, scientists announced today (Aug. 29) in the journal Science.

"You think that everything that could be known about the land surface is known, but it's not," said Jonathan Bamber, lead study author and a geographer at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. "There's still so much to learn about the planet."

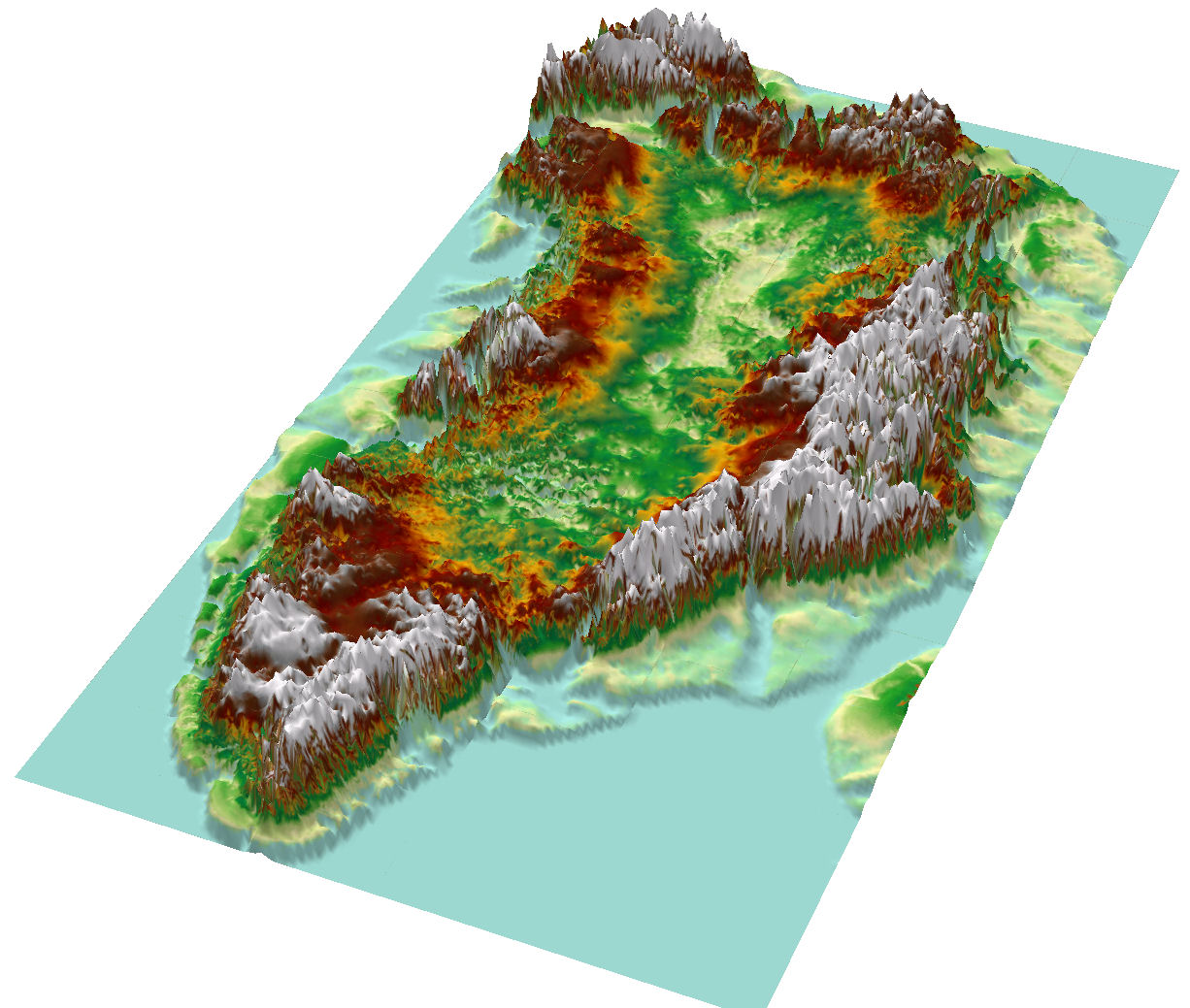

The great gorge meanders northward from Summit, the highest point in central Greenland, toward Petermann Glacier on the northwest coast, covering more than 460 miles (750 kilometers). Researchers think the ravine could be even longer, but they don't yet have the data to prove where the canyon peters out deep under the interior ice sheet. "It may actually go farther south," Bamber told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. [See Photos of Mega-Canyon Under Greenland Ice Sheet]

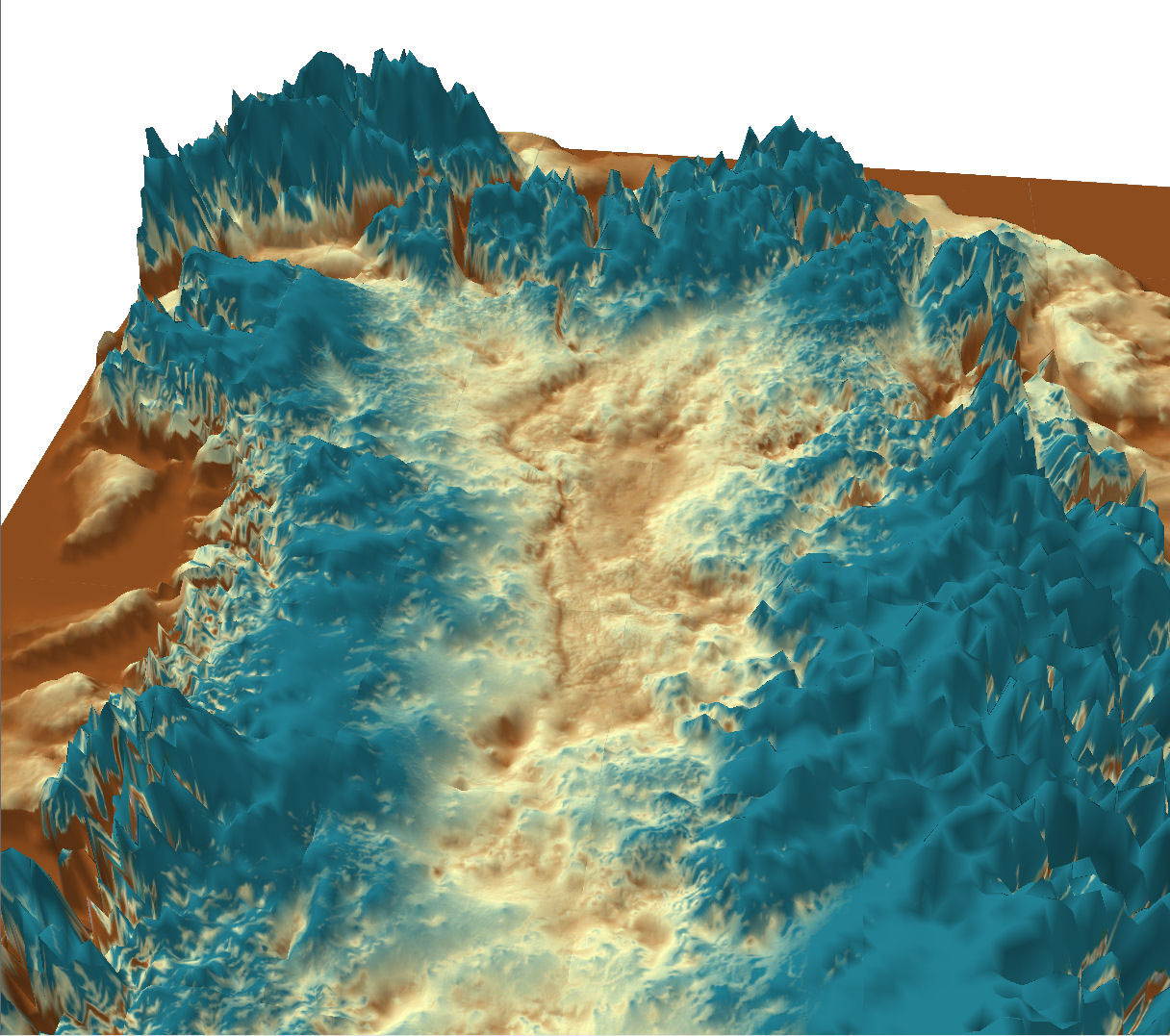

The broad chasm is up to 2,600 feet (800 meters) deep and 6 miles (10 km) wide, similar to America's Grand Canyon in scale, the researchers said. The distinctive V-shaped walls and flat bottom suggests water carved the buried valley, not ice, Bamber said. Though it is not the world's deepest canyon, it's the longest, handily besting the 308-mile-long (496 km) Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in China.

Many mysteries in what lies beneath

The discovery could raise as many questions as it answers. For instance, researchers have long puzzled over what happens to water under Greenland's interior ice sheet. Greenland bows inward like a soup bowl, yet water melting under the interior ice sheet seems to drain to the sea instead of pooling in the middle. Bamber and his colleagues think the northern canyon may route some of the meltwater into the ocean.

The great river channel could explain the missing lakes under Greenland's interior ice sheet. The weight of the ice sheet pushes down the island's middle into a bowl-shaped basin. Given this saggy middle, scientists have long wondered why Greenland isn't filled with buried lakes, like Antarctica's Lake Vostok and Lake Whillans. The northern part of the canyon may drain meltwater, but farther inland, Bamber and his colleagues think the massive weight of ice pushes water elsewhere. [North vs. South Poles: 10 Wild Differences]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It probably doesn't have water flowing through all of it today, given the interference by the ice overburden. However, when ice-free, water would channel through all of it," Siegert told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

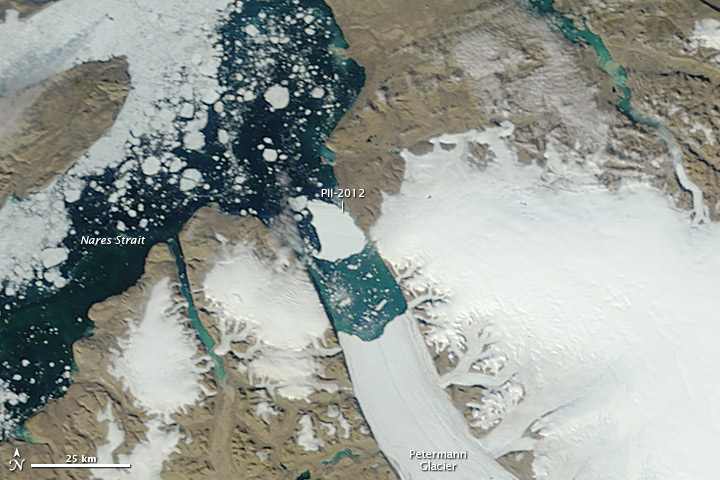

And the newly discovered canyon could boost the breakup of one of the coastline's briskly retreating glaciers. The Greenland Grand Canyon dumps right into Petermann Glacier, which has dropped two massive icebergs in the past three years, each bigger than Manhattan.

"It's fair to say that a lot of work is now needed to work out the evolution of this feature and what it means for today's ice sheet," said study co-author Martin Siegert, a glaciologist at the University of Bristol. [Fly Over Greenland's Grand Canyon]

Where the water flows

Scientists still have very little insight into how much water flows under the middle of Greenland's Ice Sheet, or where it goes, because of how hard it is to reach the thick ice, then drill under it or measure a thin film of water with radar. Yet understanding the water flow is an important part of predicting how the ice sheet will behave as the climate warms. The uncertainty means conflicting models of water movement, called basal hydrology, are often published in research journals within weeks of each other.

"When it comes to basal hydrology under the big ice sheets, we are basically scratching our heads at this point," said Michael Studinger, project scientist for NASA's Operation IceBridge, who was not involved in the study. "That's why you see contrasting results coming out." (IceBridge is a mission that uses airplanes outfitted with various instruments to measure changes in the polar ice sheets every year.)

The canyon predates the ice sheet that permanently covered Greenland about 1.8 million years ago, Siegert said. The channel curls across northwestern Greenland, ending in a deep fjord filled by Petermann Glacier. The find opens a whole new set of ideas to explore for scientists studying the glacier's rapid retreat.

"If there is a channel that can transport subglacial meltwater all the way from the interior of Greenland to the coast, that flows right into Petermann Glacier, you change the whole water circulation there and have a big impact on stability," Studinger said in an interview. "This is one of the biggest glaciers in Greenland and it produces a lot of big icebergs," he said.

Crikey!

The new canyon isn't the first amazing polar discovery from Bamber and his colleagues, who are experts in creating models of the polar regions, but it is one of the most incredible, they say. Siegert compared it to learning of Lake Vostok in Antarctica. "When Jonathan came into my office and put [the] papers on my desk, it was a jaw-dropping experience," Siegert said.

The gorge popped out of airborne radar data collected by NASA's Operation IceBridge and many other Arctic surveys. The radar onboard the IceBridge plane penetrates the ice, revealing the landscape below. Hints of a linear feature in northwest Greenland had appeared in earlier bedrock maps, but no one ever had enough detail to find the canyon until now, Bamber said.

"It wasn't exactly a 'Eureka' moment, but as we worked up the data, we realized there was something there that looked pretty extensive," Bamber said. "We looked at some profiles across it just to make sure it was what we thought it was, and it very much looked like a river profile," he said. "I thought, 'Well, crikey, we've discovered a 500-mile-long paleoriver.'"

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus