Boom! Calif. Building's Destruction Reveals Earthquake Risk

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

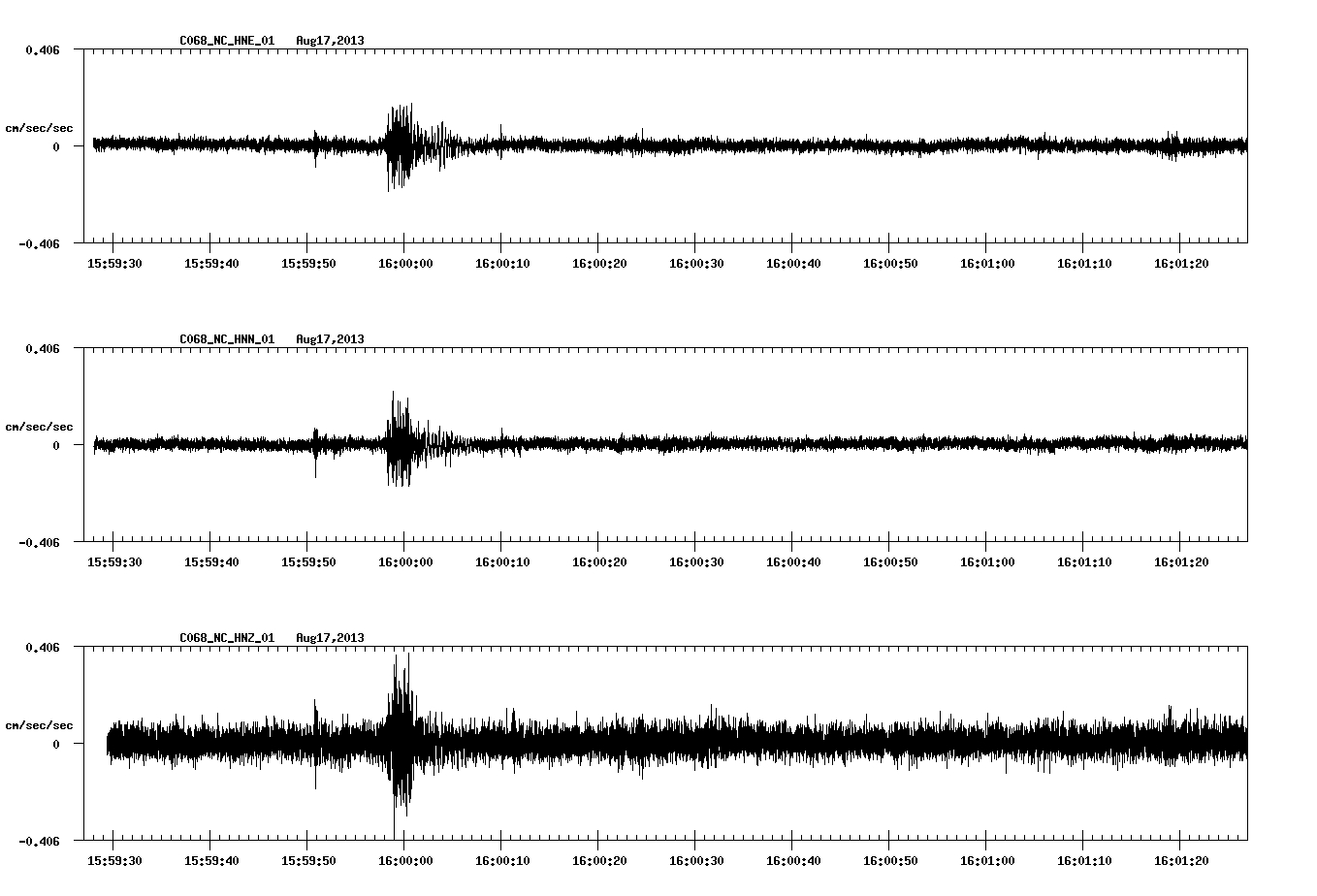

On Saturday morning (Aug. 17), a tiny artificial earthquake raced through California's East Bay, a densely populated area of valleys and hills across the bay from San Francisco. Triggered by a building implosion at California State University, East Bay, in Hayward, the seismic waves were recorded by more than 500 seismometers set out in backyards and businesses by volunteers the week before the building's collapse.

The massive effort, coordinated by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), will provide the best picture to date of which areas could suffer the worst shaking in future earthquakes on the dangerous Hayward Fault, said project leader Rufus Catchings, a research geophysicist with the USGS in Menlo Park, Calif.

"This will give us a chance to really improve our shake map, which is something that comes out immediately after an earthquake to tell first responders which areas are most affected," Catchings told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

The artificial quake was a byproduct of Saturday morning's destruction of Warren Hall, a 13-story building that was considered to be the building in the California State University system most likely to suffer severe damage during an earthquake. The hall was built about 2,000 feet (600 meters) from the Hayward Fault, which has a 31 percent chance of producing a magnitude-6.7 or greater earthquake in the next 30 years, according to the USGS. [Video - Watch Warren Hall fall]

The temporary seismometers placed before the building's destruction, will reveal where the sediment in the valley jiggles like jelly. This will show researchers where future earthquake shaking may be concentrated.

The researchers are also watching for what are called ridge effects, which occur when long, narrow mountain ridges amplify shaking, like a skyscraper swaying back and forth.

The science team also set off a few explosions over the weekend along the Hayward Fault near the Cal State campus, to get a better look at its underground structures, Catchings said. Called a seismic reflection and refraction survey, the small charges set off seismic waves that travel at different speeds through different layers of Earth's crust, revealing hidden structures.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Like many strike-slip faults, the Hayward fault is not a single thread that slices through the Earth's crust. Instead, it has many strands that cut back and forth across a zone of weakness. At strike-slips faults, two blocks of Earth's crust slide horizontally past one another, with little up-and-down movement.

"We know where the surface break of the [Hayward Fault] is, but we want to determine the width of the fault zone," Catchings said. "How far it extends from that break affects people who live in that zone."

Some of the Hayward Fault's strands lie hidden underground, but during an earthquake, they make shaking worse for people who live above them. "They don't even have to rupture, seismic energy just travels along these fault zones very rapidly, like a fiber optic line," Catchings said. "It generates very, very strong shaking."

The volunteers and USGS researchers, along with scientists from CSU East Bay, are collecting and downloading data from the temporary seismometers this week. The thousands of hours spent knocking on doors for asking permission to place seismometers, along with a wave of media attention, have been a boon for the USGS, which is tasked with communicating earthquake risk.

"I definitely think we will get something very good scientifically from [the project], but socially and from a safety perspective, the heightened awareness has helped out tremendously," Catchings said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus