Camels May Be Link to Deadly MERS Virus

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

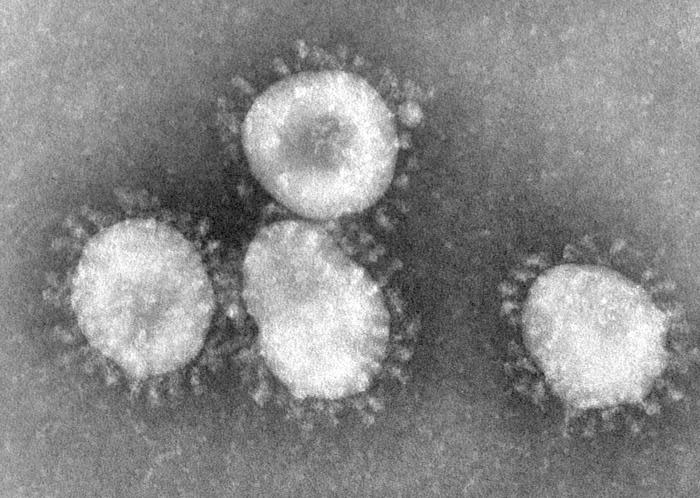

A potential source of the newMiddle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) virus has been identified: camels may be a carrier of the virus, according to a new study.

Blood tests of 50 dromedary (one hump) camels in Oman, a country in the Arabian peninsula, found that all had developed antibodies against the MERS virus, a sign that the camels may have been infected in the past with the MERS virus, or a very similar one, the researchers said. However, the actual virus was not found in the animals.

“These new results suggest that dromedary camels may be one reservoir of the virus that is causing [MERS infection] in humans,” the study researchers, from National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in Bilthoven, the Netherlands, said in a statement. “Dromedary camels are a popular animal species in the Middle East, where they are used for racing, and also for meat and milk, so there are different types of contact of humans with these animals that could lead to transmission of a virus,” the researchers said.

MERS first appeared in Saudi Arabia in September 2012, and has since infected 94 people and caused 46 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

The study did not find MERS antibodies in blood samples taken from closely related animals, such as alpacas and llamas, in the Netherlands and Chile. However, the study did not test blood from cattle, sheep and goats in the Middle East, so it's not clear if the virus is circulating in these animals in this region as well, the researchers said.

The MERS virus has been found to grow in cells taken from bats, the researchers said. (Bats are also suspected to be the source of the closely related SARS virus). However, humans do not have much direct contact with bats, so another animal, such as camels or livestock, may be an intermediate source, the researchers said.

The study cannot prove that humans caught the virus from camels. Before researchers can confirm that camels are a source of MERS, future studies are needed to identify the actual virus in camels and compare it to the MERS virus, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study is published in today's (Aug. 9) issue of the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook &Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus