New observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have helped astronomers crack a longstanding puzzle about galaxy evolution.

For years, scientists have wondered why galaxies that have ceased forming new stars — so-called "quenched galaxies" — were smaller long ago than they are today. Perhaps, they thought, ancient quenched galaxies continued to grow by merging with smaller cousins that had also stopped producing stars.

But that hypothesis is off the mark, a new study reports.

"We found that a large number of the bigger galaxies instead switch off at later times, joining their smaller quenched siblings and giving the mistaken impression of individual galaxy growth over time,"co-author Simon Lilly, of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, said in a statement.

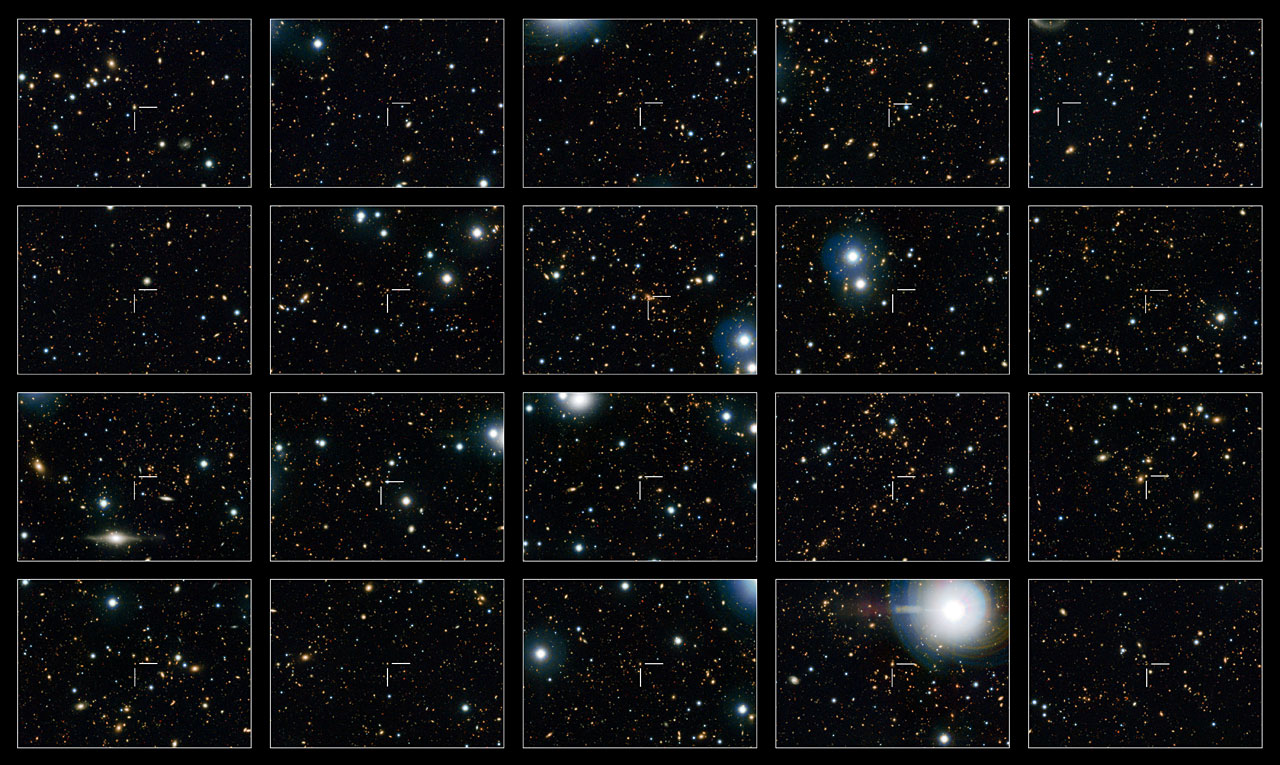

The researchers used observations from Hubble's Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS), the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope and the Subaru Telescope to map an area of the sky about nine times the size of the full moon. They used the observations to make a video of the quenched galaxies as seen by Hubble.

The team studied and tracked the quenched galaxies in this patch through the last eight billion years of the universe's history, eventually determining that most of them did not grow over time but rather remained small and compact.

So it appears that star production simply switched off earlier in older galaxies compared to younger ones. This makes sense, researchers said; star-forming galaxies were smaller in the early universe, after all, so they would hit growth and evolution milestones at a relatively smaller size.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The apparent puffing up of quenched galaxies has been one of the biggest puzzles about galaxy evolution for many years,"said lead author Marcella Carollo, also of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. "Our study offers a surprisingly simple and obvious explanation to this puzzle. Whenever we see simplicity in nature amidst apparent complexity, it's very satisfying."

The Hubble Space Telescope, a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency, has made more than 1 million science observations since its launch in 1990, and it's still going strong. NASA announced earlier this year that it had extended the telescope's science operations through April 2016.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus