Antarctic Ice Shelf Melt Sparks Seafloor Sponge Boom

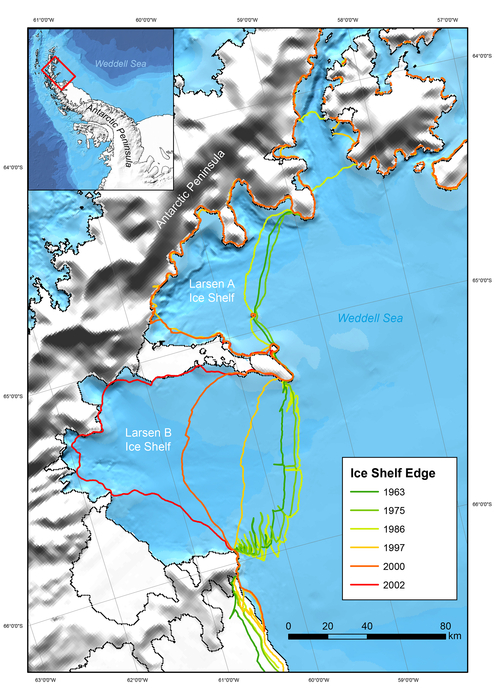

When the Larsen A ice shelf in Antarctica disintegrated almost two decades ago, the influx of sunlight breathed new life into the marine environment below. But now, the benthos, or seafloor life, is changing much more rapidly than scientists thought possible, according to a new study.

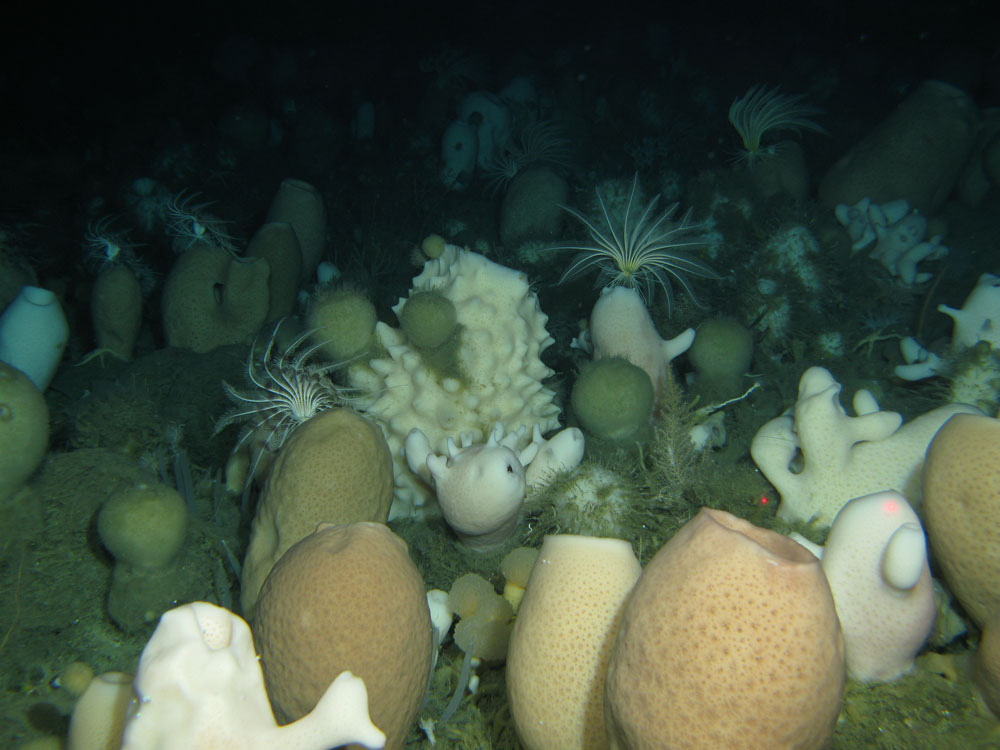

In particular, populations of glass sponges (Hexactinellida) — animals previously believed to grow and reproduce very slowly — have tripled between 2007 and 2011, allowing them to completely take over the seafloor.

"The shelf broke off, split into tiny pieces and was gone in a couple of weeks," said lead researcher Claudio Richter, a biologist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany. "Now the benthos, which we believed would take decades or centuries to move and change, is transforming quickly in just a matter of years." [Creatures of the Frozen Deep: Antarctica's Sea Life]

Nobody knows what lived beneath the floating ice shelf before it disappeared. But scientists think the seafloor communities were very poor because animals could only get food when strong currents brought it in, said Richter, who likens the thick ice shelf to a large balcony attached to a house or building, blocking the sun, which gives organisms at the base of the marine food chain energy.

"If you have a balcony that extends really far out, you would have a difficult time growing vegetables beneath it," Richter told LiveScience.

Life beneath the ice shelf

In 1995, rapidly warming waters in Antarctica's Weddell Sea caused the Larsen A ice shelf to crumble in a stunning display. In the aftermath, sunlight bathed the surface waters, allowing phytoplankton and ice algae, fed by photosynthesis, to grow. This food supply eventually trickled down to the seafloor, helping sponges, sea squirts and other animals thrive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2007, scientists aboard the ice-breaking Polarstern research vessel visited the area beneath the former ice shelf using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Though they only went down about 980 feet (300 meters), they discovered communities of deep-sea invertebrates that are normally found at depths of 3,300 feet (1,000 m) or more.

In addition, they also saw occasional small glass sponges and large populations of fast-growing sea squirts, which dominated the seafloor.

Richter and his colleagues returned to the area in 2011 and maneuvered their ROV over the original area surveyed in 2007. They found that the seafloor changed dramatically in just four years: Predatory species such as sea stars were scarce in both surveys, but glass sponges had taken over the seafloor. The pioneering species of sea squirts had all but disappeared.

In fact, despite average temperatures of 28.4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 2 degrees Celsius) and relatively low food supplies, "the sponges are now three times more numerous and two times as big as before," Richter said. What's even more astounding, he adds, is that satellite images show the area was only productive (in terms of phytoplankton and algae growth) for two out of the four years between the two surveys.

What the future holds

In contrast to what the team observed, some research has previously suggested that hexactinellid species live long, slow lives. One study found that populations of glass sponges in Antarctica's McMurdo Sound showed no growth or reproduction over a 10-year period. Other research suggests the animals have a very slow metabolism, allowing them to live for 10,000 years or more. However, scientists have also observed fast growth and reproduction in previously nongrowing settlements of glass sponges.

The new findings, taken together with other work, suggest that Antarctic glass sponges that have endured arrested growth for decades can undergo booming periods that allow them to quickly colonize new areas. At this point, it's unclear what triggers this change. "It's a complex issue," Richter said. "It's difficult to predict the evolution of how things develop, but for now, the sponges seem to be gaining pace."

Just how the glass sponge dominance will affect the rest of the Antarctic seafloor is anybody's guess, Richter notes. The animals are known to provide a habitat and build a framework for other species of fish and invertebrates, so it's possible that the Antarctic seafloor will experience an upsurge of activity as more ice shelves melt. If this is the case, the glass sponges will be on the winning end of climate change.

But at the same time, predators, such as the king crabs that are already invading Antarctica, could move in and wreak havoc on the sponge populations.

"There are still many unknowns, so it's very difficult to predict the future," Richter said. "The only thing we can predict is that things will happen very quickly."

The new research was detailed today (July 11) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Joseph Castro on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.