What Baseball Pitchers Owe to Ancient Hunters

Retired baseball pitcher Sandy Koufax is regarded as one of the most talented players to have ever stepped on the mound, but new research suggests he and other baseball greats may owe their strong throwing arms to evolution.

A new study that investigated how humans developed the ability to hurl objects with control found humans are the only species that can throw with great speed and precision, and this behavior first evolved nearly 2 million years ago, when anatomical changes to the shoulder, arm and torso likely bolstered the hunting prowess of extinct human ancestors, said study lead author Neil Roach, a postdoctoral scientist at George Washington University's Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology in Washington, D.C.

"We think that throwing was probably most important early on in terms of hunting behavior, enabling our ancestors to effectively and safely kill big game," Roach said in a statement.

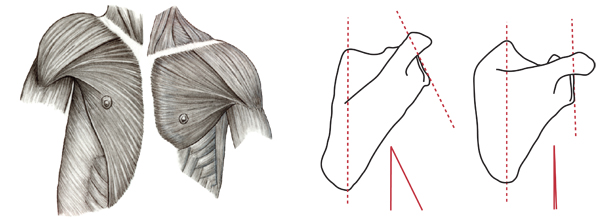

To understand the mechanics of throwing, the researchers studied the arm motions of college baseball players using 3D cameras. Roach and his colleagues observed that the power of a throw largely comes from the shoulder, which acts like a slingshot by storing and then releasing large amounts of energy. [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

"When humans throw, we first rotate our arms backwards away from the target," Roach explained. "It is during this 'arm-cocking' phase that humans stretch the tendons and ligaments crossing their shoulder and store elastic energy. When this energy is released, it accelerates the arm forward, generating the fastest motion the human body produces, resulting in a very fast throw."

Three primary features in the shoulder, arm and torso evolved in human ancestors to facilitate this type of motion and energy storage, Roach said. The anatomical changes include the expansion of the waist, which enabled the torso to rotate independently from the hips; the lowering and relaxation of the shoulders, which altered the orientation of many of the muscles that store energy; and the twisting of the upper arm bone that helped humans build up more energy during throws.

These changes in bone and muscular anatomy likely occurred about 2 million years ago among early human ancestors, called Homo erectus, the researchers said. The evolved features would have helped early humans become more skilled at hunting large game, they added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The ability to throw was one of a handful of changes that enabled us to become carnivores, which then triggered a host of changes that occurred later in our evolution," study co-author Daniel Lieberman, a professor of biological sciences at Harvard University, said in a statement. "If we were not good at throwing and running and a few other things, we would not have been able to evolve our large brains, and all the cognitive abilities such as language that come with it. If it were not for our ability to throw, we would not be who we are today."

The researchers said this unique throwing skill does not seem to have evolved in other animals, including chimpanzees.

"Chimpanzees are incredibly strong and athletic, yet adult male chimps can only throw about 20 miles per hour — one-third the speed of a 12-year-old Little League pitcher," Roach said.

The researchers intend to build on these findings by combing through archaeological records to determine the types of objects early human ancestors were likely throwing, Roach said.

The new study's findings were published online today (June 26) in the journal Nature.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus