Trash Litters Deep Seafloor, Mostly Recyclables

The mention of ocean pollution usually triggers searing images of birds and turtles choked by bags, fasteners and other debris floating at the ocean surface. But thousands of feet below, garbage also clutters the seafloor, with as yet unknown consequences for marine life, a new study finds.

"It's completely changing the natural environment, in a way that we don't know what it's going to do," said Susan von Thun, a study co-author and senior research technician at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in Monterey, Calif.

For the past 22 years, MBARI researchers have explored the deep ocean seafloor from California to Canada and offshore of Hawaii. Video researchers tagged every piece of trash seen during the deep-sea dives, cataloguing more than 1,500 items in all. Sparked by a recent study on trash offshore of Southern California, scientists at MBARI decided to analyze the database of ocean debris they had gathered. The results were published May 28 in the journal Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers.

After reviewing every video clip that showed debris, and compiling where and when the debris was found, the researchers discovered plastics were the most common seafloor trash. [Video: Deep Sea Trash Litters the Ocean Floor]

"Unfortunately for me, I wasn't so surprised," said von Thun, who works in the MBARI video lab. "I've seen plenty of trash as I've been annotating video."

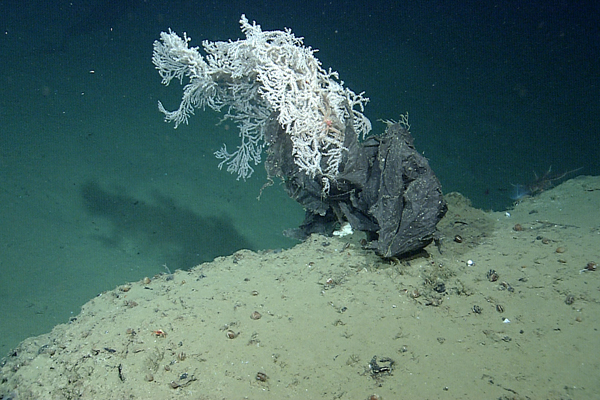

More than half of the plastic items were bags. A deep-sea coral living nearly 7,000 feet (2,115 meters) off the Oregon Coast had a black plastic bag wrapped around its base, which will eventually kill the organism, von Thun said.

The second biggest source of ocean trash was metal — soda and food cans. Other common types of debris included rope from fishing equipment, glass bottles, cardboard, wood and clothing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because most of the ocean pollution came from single-use plastic bottles and cans, von Thun and her co-authors hope the research will inspire more people to reduce, reuse and recycle.

"The main way to combat this problem is to prevent all this stuff from getting into the ocean to begin with," von Thun told OurAmazingPlanet. "We really have to properly dispose of items, reduce our use of single-use items and recycle."

Changing seascape

The arrival of shoes, tires and fishing gear in the deep sea is a big change for deep-sea marine life. Their environment is mostly soft mud, so hard surfaces are rare, and sea creatures colonize the trash, von Thun said. For example, MBARI is following the effects wrought by a shipping container that fell overboard into Monterey Canyon in 2004. But even a discarded tire can make a home for certain sea creatures at 2,850 feet (868 meters) below the ocean surface.

In Monterey Canyon, a deep, winding gorge offshore of Central California, trash collects in the canyon's outer bends or in topographic highs or lows, just like in rivers on land, von Thun said. Currents also trap trash behind obstacles, such as dead whale carcasses.

"We think the canyon dynamics and the currents are actually helping to distribute the plastic and metal to deeper areas," von Thun said.

With only 0.24 percent of Monterey Canyon explored in the past two decades by MBARI, there could be more trash hidden in the canyon's depths, the researchers said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus