AIDS Epidemic: Is an End Possible?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

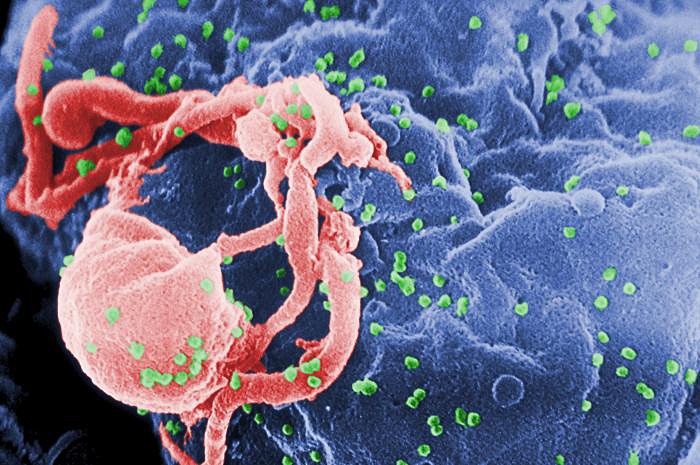

NEW YORK CITY — More than 30 years after the discovery of the AIDS virus, experts are optimistic that a cure for the disease will be found, and that an end to the AIDS epidemic is possible.

But they caution there is still a lot of work to be done.

Since the first cases of AIDS were reported in 1981, more than 25 million people worldwide have died of AIDS. There are currently 33 million people living with AIDS, including 1 million in the United States. There are 50,000 new infections in the United States each year.

Three methods that are being explored to end the AIDS epidemic are drugs, vaccines and gene therapy.

There are already drugs that can prevent AIDS, which is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Recent research has shown that taking antiretroviral drugs not only reduces the amount of HIV in the body, it can also stop transmission of the virus. People at high risk for contracting HIV can now take a daily pill to prevent infection, Dr. Robert Grant, an HIV researcher at the Gladstone Institute of Virology and Immunology, said here Friday (May 31) at a panel at the World Science Festival.

But others say these drugs will not be enough to stop AIDS spread.

"We've got to find a way to immunize people, so that they don't have to take an action to protect themselves," said David Baltimore, a noble prize winner and professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology, who also spoke on the panel. "That's how public health works." [Watch the World Science Festival Live]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1984, Margaret Heckler, the Secretary of Health and Human Services at the time, said that a vaccine against HIV was expected within two years. But today, no vaccine exists, and most trials testing HIV vaccines have failed to show any benefit.

The reason making an HIV vaccine is so difficult is because the virus has already found a way around the body's defense — it is able to invade immune cells, the very cells that are supposed to attack it.

But recently, researchers have devised new ways of creating HIV vaccines.

One method uses stem cells that are engineered to develop into immune cells that lack the port of entry for the HIV virus. Without this port, or receptor, HIV can't get inside to thwart the immune system's attack.

Another approach is to use gene therapy to get the body to make special immune cells, called broadly neutralizing antibodies, which are capable of preventing HIV infection. Most people don't make these antibodies in response to HIV. But the gene therapy gives cells the genetic material they need to make the antibodies.

Both the stem cell and gene therapy methods were invented by Baltimore and colleagues. Baltimore said he hopes to start a trial for the stem cell therapy next month, and one for the gene therapy within a year.

Experts point out that even when a trial fails, researchers can still learn something. "It's only through failure that you get to success," Grant said.

Peter Staley, an AIDS activist, said he expects a cure within his lifetime, perhaps within the next 15 years. "Everybody thinks it can be done, it's just a matter of time and effort," Staley said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily @MyHealth_MHND, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on LiveScience .

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus