Coral Bleaching Event Linked to Spike in Caribbean Sea Temperatures

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

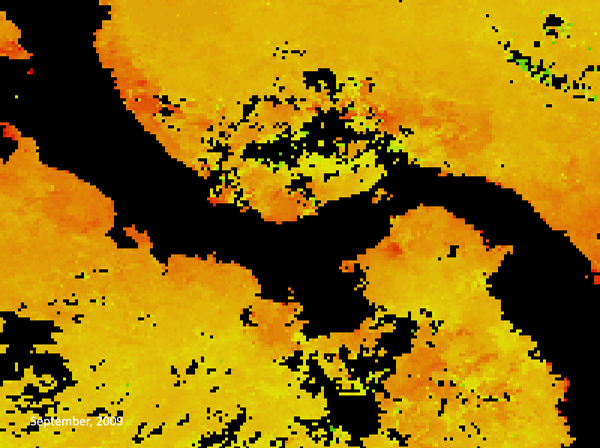

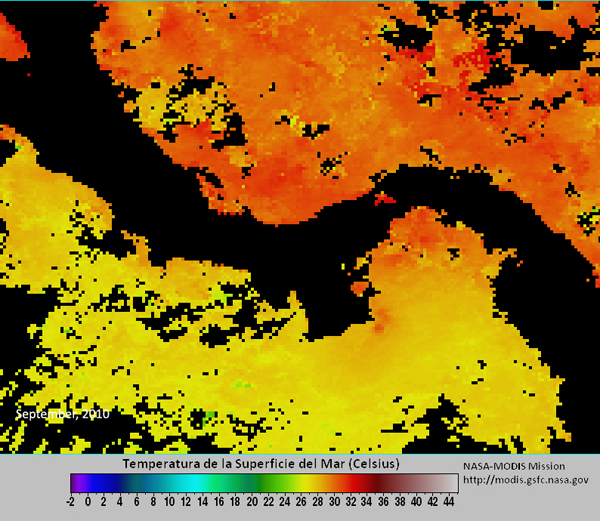

Scientists and local divers in the Western Caribbean have reported a major coral bleaching event in the area, due to an increase in ocean temperature.

They first noticed bleaching in the waters surrounding Isla Colon, in Panama's Bocas del Toro province in July, and more extensive coral bleaching was noted by the end of September.

Researchers recorded a high seawater temperature of 89 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius). Normal temperatures at this time of year are closer to 82 degrees F (28 degrees C). This warming event currently affects the entire Caribbean coast of Panama and has also been reported at sites in Costa Rica.

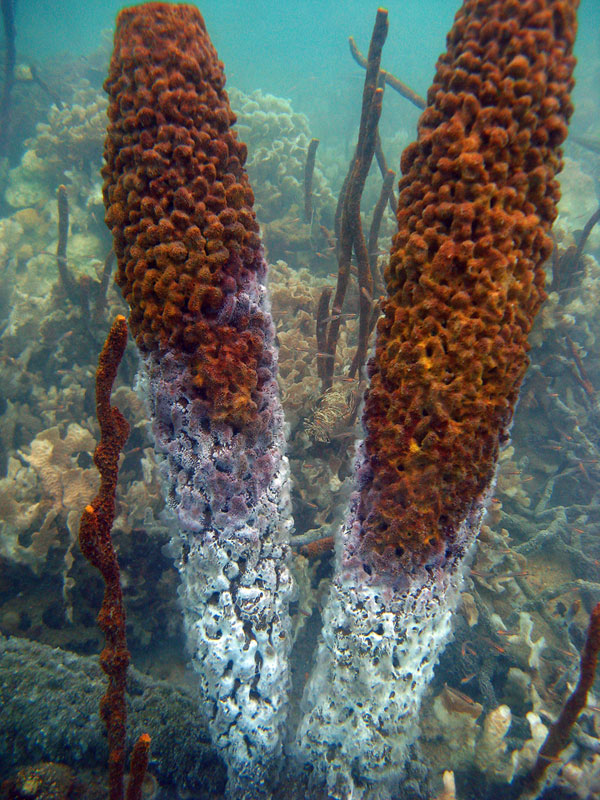

Coral polyps, the tiny organisms that make up a coral reef, contain photosynthetic algae called zooxanthellae, which provide the coral with food (and also with color). Coral bleaching occurs when zooxanthellae leave the coral due to increased water temperature or other stress factors, and so the coral structure appears white. Without means to food, the bleached coral have trouble reproducing and growing, and if the bleaching event lasts long enough, they can die.

As the corals die, the release great quantities of mucous into the surrounding water, making it appear increasingly cloudy. These cloudy conditions create the perfect environment for bacteria and fungi to grow, which may cause a decrease in the water's oxygen content. Anoxic conditions affect fish and coastal productivity.

"Dissolved oxygen dropped to less than 3 milligrams per liter at 33 feet (10 meters), and nearly zero milligrams per liter at the bottom," said Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) technician Plinio Gondola, who recorded the measurements.

The final outcome of this event is uncertain. A similar event in 2005 in the wider Caribbean included intense bleaching in Panama. However, coral mortality was less that 12 percent in this zone, and reefs have been relatively resilient.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hurricane season may be enhancing the current problem, resulting in low water circulation in the southwestern Caribbean and thus creating a "warm pocket" of water along the coasts of Panama and Costa Rica, the researchers speculate.

The work is part of an extensive coral reef monitoring network in Panama, established over a decade ago by staff scientist Héctor M. Guzmán of STRI and partially funded by the Nature Conservancy. The network consists of 33 sites along both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of the isthmus of Panama.

So far, coral mortality has been limited to shallow areas near Isla Colon and a semi-lagoon area in Bocas del Toro, which is considered to be particularly vulnerable to bleaching as water circulation there is slow and temperatures tend to rise quickly.

Researchers expect to have a complete report on the state of the coral reefs in several weeks.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus