Intricate Pattern Has Surprising Origin

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

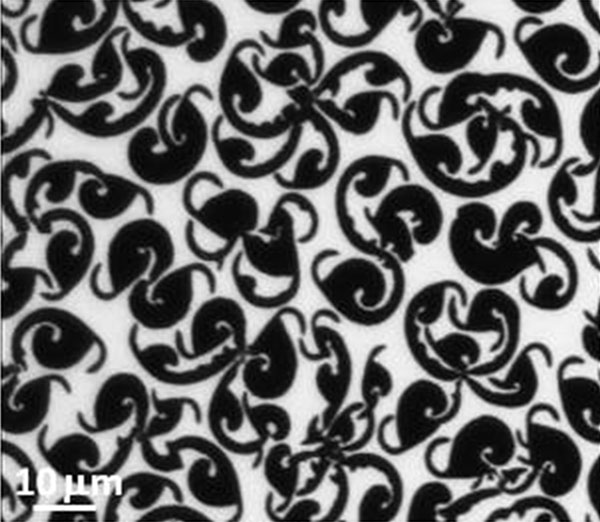

A beautiful black-and-white image that looks like the pattern on a scarf isn't the work of an upscale French designer. It's the stuff that lines your lungs.

The snapshot is a microscopic image that used fluorescent dye to reveal the patterns made by lung surfactant, a soaplike material that covers the inside of the lungs. Without surfactant, the lungs would collapse.

"During the breathing cycle, as your lung is compressed, it will form this pattern," said Prajna Dhar, the creator of the striking microscopic image. Dhar and her colleagues published the picture in January 2012 in Biophysical Journal. This March, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences featured the image in their monthly newsletter, Biomedical Beat. [Tiny Grandeur: Stunning Photos of the Very Small]

The researchers took the patterned surfactant image as part of a study investigating how nanoparticles affect the body. Nanoparticles are particles so tiny they're measured in billionths of a meter. They're the subject of major scientific research right now, because engineering on a nano-scale allows scientists to literally build materials atom by atom, like this world map one-thousandth the size of a grain of salt. Nanotechnology is being used to develop everything from nano-scale solar cells to medicine delivery systems.

The explosion in technology has led to concern that nanoparticles might harm human health, Dhar told LiveScience. The question is whether the tiny particles are toxic or not.

To find out, Dhar and her colleagues exposed lung surfactant molecules to nanoparticles made of carbon — "really tiny nano-diamonds," Dhar said. They found that in the short term, the particles don't affect how surfactant changes as lung tissue compresses and expands. But over time (the researchers looked at exposures up to 21 days), the nanoparticles changed the way the surfactant "packed" when compressed by exhaling lung tissue.

"If it changes the way the surfactant packs, it destabilizes the sufactant," Dhar said. "And if it destabilizes the surfactant, than you cannot lower the energy that is required to breathe."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The effect of the particles lodging in the lungs is similar to what happens after a long period of secondhand smoke exposure, Dhar said, or to black lung disease. This disease occurs in coal miners who have breathed coal dust (also made of carbon) for many years. The lungs can't rid themselves of fine dust particles, so they accumulate, causing inflammation, formation of excessive fibrous tissue, and even death of the lung tissue.

The effect of nanoparticles on lung tissue is different depending on the size, shape and material of the particles, Dhar said. She and her colleagues hope to use their lung-based surfactant system to test nanomaterials for safety, expanding to particles other than carbon. Testing the particles on animals is less effective, she said, because black lung-like symptoms may take an animal's entire life to develop. Exposing surfactant directly to the nanoparticles is far faster.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus