Rhino 'Cooked to Death' 9 Million Years Ago, Fossil Reveals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 9.2 million years ago, a teenage two-horned rhinoceros was literally cooked to death when a Mt. Vesuvius-like eruption enveloped it in lava reaching more than 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius), scientists say.

The perhaps fortunate result: a well-preserved skull of the Rhinocerotid, with a tale to tell.

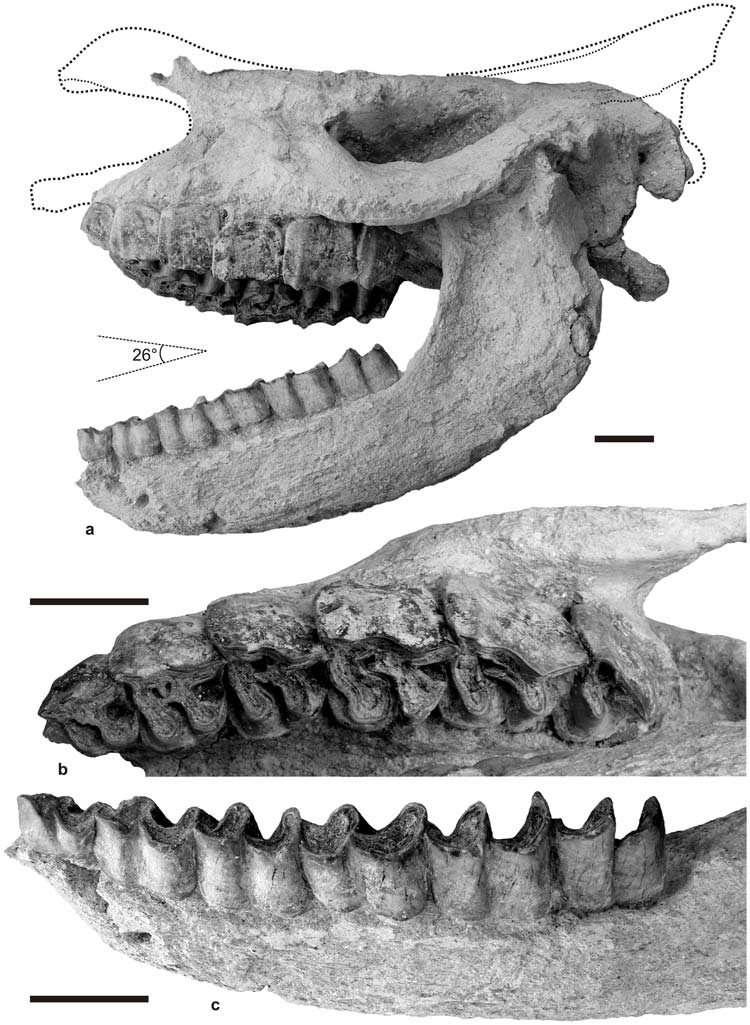

An analysis of the volcanic rock-preserved skull suggests the animal's grisly death was near instantaneous. "[T]he body was baked under a temperature approximating 400°C, then dismembered within the pyroclastic flow, and the skull separated from body," the researchers wrote online Nov. 21 in the journal PLoS ONE. The flow of volcanic ash carried the detached skull about 19 miles (30 kilometers) north of the eruption site and to the site where it was discovered in Cappadocia in Central Turkey.

"The articulated skull and mandible were found alone, and there were no other rhino bones in the surroundings, except for some rib fragments, potentially of rhino affinities," said study researcher Pierre-Olivier Antoine of the University of Montpellier in France. [See Photos of the Volcano-Preserved Rhino Fossils]

When alive, the rhino (Ceratotherium neumayri) would have weighed between 3,300 and 4,400 pounds (1,500 and 2,000 kilograms), about the size of a young white rhino, though sporting a shorter head, Antoine said. The animal was 10 to 15 years old, a young adult, when it died in a Pompeii-style eruption.

Antoine has excavated dozens of fossil skulls in the past 19 years, and he said the external surfaces of this one were "quite unusual." For instance, "the bony surface was rough and corrugated all around the skull and mandible, and the dentine (the internal component of the teeth) was incredibly brittle, and even kind of 'corroded' [in] places," Antoine told LiveScience in an email.

When they looked at the remains under a microscope the researchers found structural changes that suggested the animal had been heated to the high temperatures of volcanic flows.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

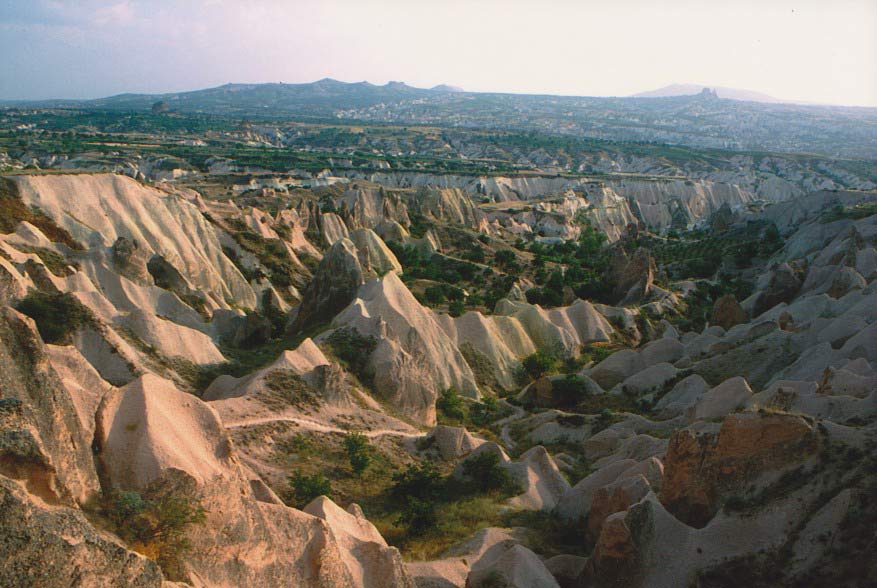

"There was not a real volcano, but a caldera which spread huge amounts of volcanic ash over Cappacocia, during millions of years, throughout the late Miocene-Pliocene interval," which lasted from about 9.5 million to 3 million years ago, Antoine said. Examples of similar calderas, albeit much smaller ones, are Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines and Krakatoa, a volcanic island west of Jakarta, Indonesia.

The so-called Çardak caldera is inactive today. Even so, thick layers of volcanic ash have accumulated over millions of years. "Then, erosion generated there among the most magnificent landscapes I've ever seen," Antoine wrote.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus