7 Ways Animals Are Like Humans

Animals and Humans

We humans like to think of ourselves as a special bunch, but it turns out we have plenty in common with other animals. Math? A monkey can do it. Tool use? Hey, even birds have mastered that. Culture? Sorry, folks — chimps have it, too.

Here's a list of some of the top parallels between humans and our animal kin. You may be surprised at how similar we are to even our distant relations.

Ears Like a Katydid

Humans have complex ears to translate sound waves into mechanical vibrations our brains can process. So, as it turns out, do katydids. According to research published Nov. 16, 2012 in the journal Science, katydid ears are arranged very similarly to human ears, with eardrums, lever systems to amplify vibrations, and a fluid-filled vesicle where sensory cells wait to convey information to the nervous system. Katydid ears are a bit simpler than ours, but they can also hear far above the human range.

Worlds Like an Elephant

Humans do reign supreme in the arena of language (as far as we know), but even elephants can figure out how to make the same sounds we do. According to researchers, an Asian elephant living in a South Korean zoo has learned to use its trunk and throat to mimic human words. The elephant can say "hello," "good," "no," "sit down" and "lie down," all in Korean, of course.

The elephant doesn't appear to know what these words mean. Scientists think he may have picked up the sounds because he was the only elephant at the zoo from when he was 5 to when he turned 12, leaving him to bond with humans instead.

The Facial Expressions of a Mouse

Do you make weird faces when you're in pain? So do mice. In 2010, researchers at McGill University and the University of British Columbia in Canada found that mice subjected to moderate pain "grimace," just like humans. The researchers said the results could be used to eliminate unnecessary suffering for lab animals by letting researchers know when something hurts the rodents.

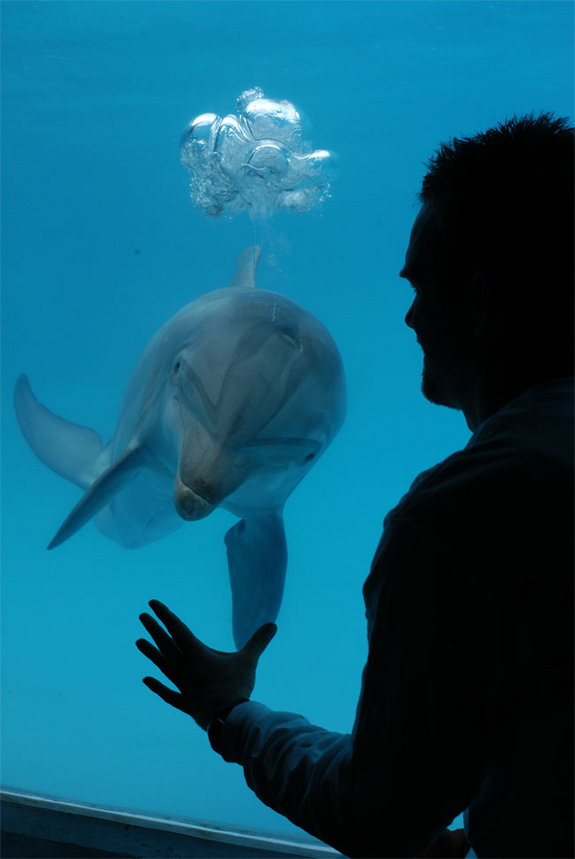

The Sleep-Talk of a Dolphin

Dolphins may sleep-talk in whale song, according to French researchers who've recorded the marine mammals making the non-native sounds late at night. The five dolphins, which live in a marine park in France, have heard whale songs only in recordings played during the day around their aquarium. But at night, the dolphins seem to mimic the recordings during rest periods, a possible form of sleep-talking. And you thought your nocturnal mumblings were weird.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The House-Building Skill of an Octopus

Okay, Frank Lloyd Wright's "Falling Water" it is not, but a home built by an octopus has the advantage of being mobile.

The veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) can make mobile shelters out of coconut shells. When the animal wants to move, all it has to do is stack the shells like bowls, grasp them with stiff legs, and waddle away along the ocean floor to a new location.

The Movements of a Brittle Star

It'd be hard to imagine an organism less like a human than a brittle star, a starfish-like creature that doesn't even have a central nervous system. And yet these five-armed wonders move with coordination that mirrors human locomotion.

Brittle stars have radial symmetry, meaning their bodies can be split into matching halves by drawing imaginary lines through their arms and central axis. Humans and other mammals, in comparison, have bilateral symmetry: You can split us in half one way, with a line drawn straight through our bodies. Most of the time, animals with radial symmetry move little or move up and down, like a jellyfish that propels itself through the water. Brittle stars, however, move forward, perpendicular to their body axis — a skill usually reserved for the bilaterally symmetrical.

Brain Like a Pigeon

Gamblers in Vegas have something in common with pigeons on the sidewalk, and it's not just a fascination with shiny objects. In fact, pigeons make gambles just like humans, making choices that leave them with less money in the long run for the elusive promise of a big payout.

When given a choice, pigeons will push a button that gives them a big, rare payout rather than one that offers a small reward at regular intervals. This questionable decision may stem from the surprise and excitement of the big reward, according to a study published in 2010 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Human gamblers may be similarly lured in by the idea of major loot, no matter how long the odds.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus