Will Earth Run Out of Plants?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Humans may be very close to extracting all of the Earth's available plant resources, says a University of Montana researcher.

In fact, said Steven Running, a professor in the university's College of Forestry and Conservation, humanity may realistically have only 10 percent or so of our planet's annual plant resources in reserve, with little ability to boost yearly growth. The calculations don't suggest that humanity is on the verge of starvation, Running said, but they do indicate there are limits to our species' growth.

"Economic logic just seems to be about endless growth with no limits," Running told LiveScience. "And this is my attempt to say that on the planet we at least have some biophysical limits, and here's one."

Boundaries to growth

The concept of resource-imposed limits to growth, or "planetary boundaries" first came up in the 1970s with the book "Limits to Growth" (Club of Rome, 1972). The authors of that book modeled the planet's productivity and predicted that population and economic growth would run up against basic resource scarcity sometime around 2030. The calculations were somewhat primitive, Running said. The methodology and findings of the modeling were criticized, though researchers have recently revisited the predictions and found them to be relatively accurate. One 2011 analysis, published in book form by SpringerBriefs in Energy found that "reality seems to be closely following the curves that the [Limits to Growth] scenarios had generated."

Climate change and other environmental concerns have prompted scientists to revisit the idea of planetary boundaries, Running said. Likewise, he said, environmental policy-makers have become more interested in whether those boundaries can be defined. Researchers have suggested that important boundaries might include climate change, ocean acidification, land-use change and loss of species. [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

A new line

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

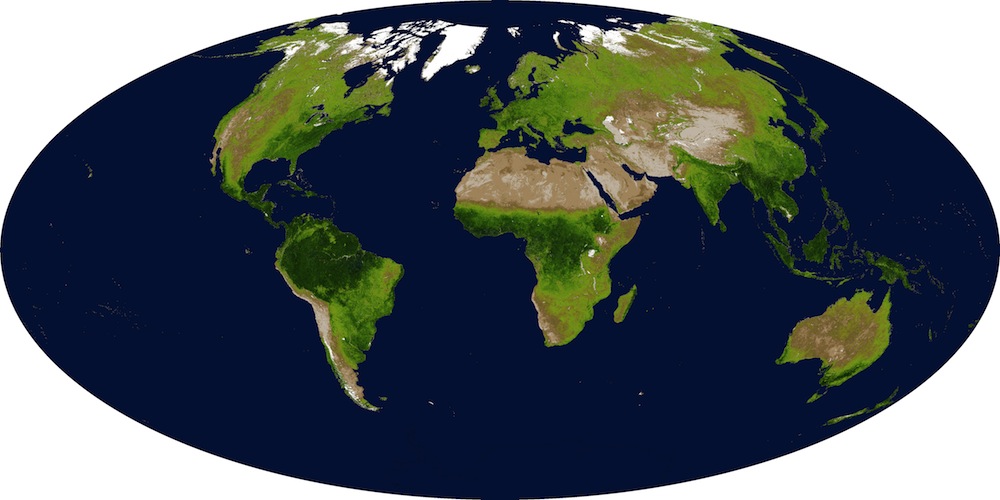

In an editorial in the journal Science to be published Friday (Sept. 21), Running suggests a new measure: terrestrial net primary plant production. This mouthful merely refers to the globe's land plant growth in a year. Humans depend on plant life for food, building materials, firewood and bioenergy and grazing land for livestock.

Thanks to satellite measurements, researchers can now calculate how much vegetation the Earth produces each year. Over 30 years of observation, Running said, the number has stayed remarkably stable at 53.6 petagrams (one petagram is one trillion kilograms, or about 2.2 trillion pounds).

That's a lot of greenery. But humans use about 40 percent of it annually, Running said. The number would seem to offer plenty of wiggle room for humanity, but in fact, only about 10 percent of the remaining vegetation is up for grabs, he said.

"What we've found is that the vast majority of that other 60 percent isn't available at all," he said. It's either locked up in root systems and unharvestable, conserved in national parks or wilderness areas crucial for biodiversity, or simply in far Siberia or the middle of the Amazon, where there are no roads and no way to harvest it.

"If humans are appropriating about 40 percent of annual production, if another 50 percent we can't harvest and appropriate, then that only leaves about 10 percent," Running said. "Well, that starts to sound a lot closer to a planetary boundary."

The boundary debate

There are arguments against this imminent vegetal limit, Running said: It's arguably possible that humanity could increase plant production with fertilizer or irrigation (though both of those are also in limited supply and have downsides such as pollution), or that we could construct more roads into the Amazon to avail ourselves of more natural resources. But a large enough boost to make a significant difference would have to number in the tens of percentage points, Running said, which seems unlikely. [10 Most Pristine Places on Earth]

"And again, you would question how far that would go and whether that's a planet we want, where every single acre from wall to wall has been completely harvested and is in some sort of controlled annual plant production cycle," he said.

The findings are also an argument against hoping the biofuels will solve the planet's energy woes. Running calculated that if humans turned every bit of the last 10 percent of available plant production to bioenergy, it would only cover 40 percent of current energy needs.

"Endless economic growth and endless consumptive growth of the planet just can't happen," Running said. "And that the sooner we start getting realistic expectations for the future, the better we can manage ourselves to effectively use the planetary resources in a sustainable way."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus