Water Droplet Computing Needs No Electricity

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Today's computers can short out if liquid enters their innards, but water droplets could form the basis for tomorrow's electricity-free computing devices.

The idea of turning water droplets into digital bits — the basic unit of data transfer — came from experiments at Aalto University in Finland. When researchers observed water droplets bouncing off one another like billiard balls on a water-repellent surface, they realized they could guide the water droplets along water-repellent tracks.

"I was surprised that such rebounding collisions between two droplets were never reported before, as it indeed is an easily accessible phenomenon: I conducted some of the early experiments on water-repellent plant leaves from my mother's garden," said Henrikki Mertaniemi, an applied physics researcher at Aalto University, in a statement.

The experiments showed how the water droplets could act as digital bits in memory devices or logic operations at the most basic level of computing.

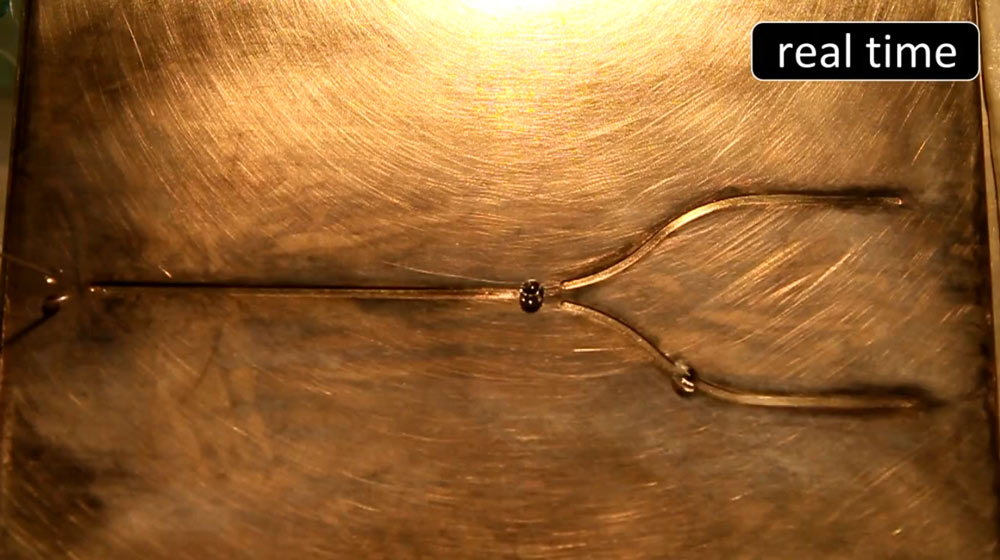

For example, researchers demonstrated a "flip-flop memory" setup with a single water-repellent track forking into two tracks. A series of water droplets rolling down the single track would collide with second droplet sitting at the fork, and alternatively knock the second droplet toward one fork branch or the other — a process repeated 100 times without error.

Researchers also raised the possibility of "programmable chemical reactions." They turned water droplets into timed chemical triggers by loading them with chemicals, allowing the droplet collisions to set off the chemical reactions.

The idea of water-based computing likely won't replace your PC or Mac, but it could lead to specialized computing in devices that don't have power sources — or in situations where you can't rely on having available power outlets.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Water computers join other wild ideas for futuristic computing that have arisen in recent years, such as test tubes filled with DNA or the genetic code of living cells.

The water computing study appears in the Sept. 4 issue of the journal Advanced Materials.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus