Fiery Folklore: 5 Dazzling Sun Myths

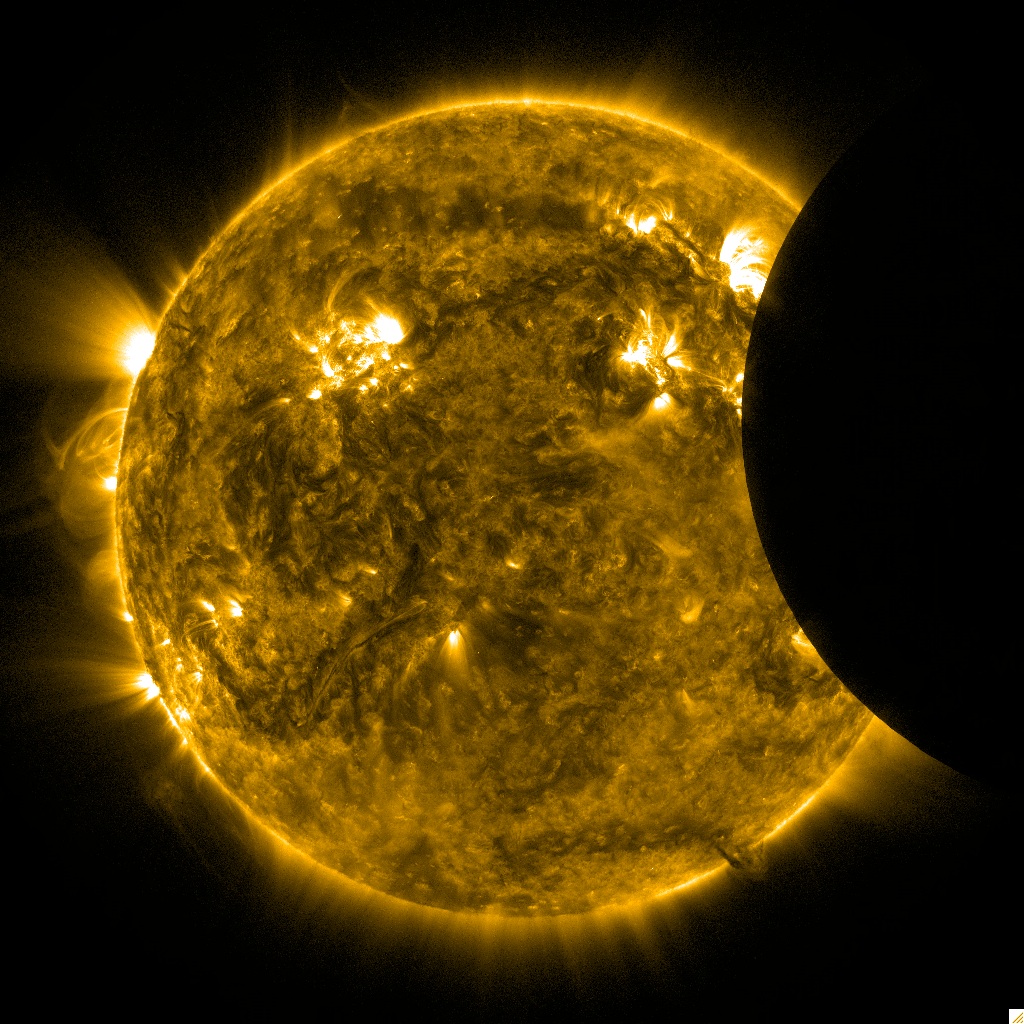

The next partial solar eclipse Earthlings will be able to see will occur May 20, with views visible from Asia, the Pacific and western North America. (Image credit: NASA/SDO)

On Sunday (May 20), a solar eclipse will blot out the sun for viewers across much of Asia, the Pacific and western North America. These days, eclipses aren't a big mystery — they occur when the moon passes between Earth and the sun. But throughout history, the sun's significance, along with its mysteriousness, have yielded an array of solar myths.

From the fearsome figures that try to devour the sun to nine lost suns of the Chinese sky, here are the stories that have sought to explain our nearest star.

How Hou Yi shot the sun

In ancient Chinese mythology, the sky had not one, but 10 suns. Every day, the solar goddess Shiho would pick up one of these suns (also her sons) and wheel him across the sky in her chariot. In the meantime, the other nine would play among the leaves of the mythical Fusang tree, believed to be more than 10,000 feet tall. [Gallery of Sun Gods and Goddesses]

This system worked well until the day that the suns grew bored of their responsibility. They decided to run across the sky all at once, planning to generate enough light and heat so that they could all take a few days off. Instead, this solar scamper dried up rivers, scorched the Earth and led to widespread drought.

Taking pity on suffering mortals, the sun god Dijun called in the expert archer Hou Yi. With 10 magic arrows, the story goes that Hou Yi was to discipline the irresponsible suns. The archer stalked and killed nine suns and would have snuffed out the last as well if a young boy hadn't stolen his final arrow, saving Earth from perpetual darkness.

Ancient Chinese myth also holds that solar eclipses were caused by a demon or dragon devouring the sun, leading to a tradition in which people would play drums or bang pots to scare the sun-eater away. In actuality, Chinese astronomers seemed to understand eclipses as natural phenomena dating back at least as far as 720 B.C., with older observations scratched into bones dating back perhaps 3,000 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Chased by wolves

In ancient Norse legend, the sun goddess Sol travels through the sky chased by the wolf Sköll, who intends to devour her. (Sköll's brother Hati does the same to the moon at night.) Eclipses were said to be a sign that Sköll was dangerously close to catching Sol.

In fact, the Norse believed that one day, the sun would finally be devoured. Mythology foretold a huge battle called Ragnarök, in which major gods would die and the Earth would be engulfed in a massive flood. This apocalypse would wipe the Earth, clean to be repopulated by a pair of human survivors. [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

Sailing the sun boat

One of the most important deities in the Egyptian pantheon was Ra, the falcon-headed sun god. Legend had it that every day Ra captained a boat crewed by gods across the sky. (This boat was called Mandjet, or the "Boat of Millions of Years" — an underestimate, given that our star is actually about 4.5 billion years old.)

At night, Ra returned to the east via the underworld, bringing light to the dead. It was a treacherous journey: Apep, an evil serpent god, attempted to stop Ra by devouring him. Solar eclipses were thought to be days when Apep got the upper hand, though Ra always managed to escape.

Jealous star

According to a Cherokee legend, the sun long ago grew jealous of her brother the moon because the people of Earth always looked at her with twisted-up faces and squinted eyes, while they smiled at his gentle light. The sun's daughter lived in the middle of sky, so every day, the sun stopped to visit her. Angry at humans for their ugly expressions, the sun began using these opportunities to send down so much heat that people began to die of fever.

The humans turned to the Little Men, who in Cherokee legend were friendly, magical spirits who dwelt in the forests. The Little Men said that the sun must die, so they turned one man into a rattlesnake and another into a fearsome antlered serpent called the Uktena.

The rattlesnake arrived at the sun's daughter's house to wait for her arrival. But while he was waiting, the sun's daughter opened her door. The rattlesnake accidentally bit her, killing her. When the sun came to see her daughter, she discovered her dead and began to weep, flooding the Earth with her tears.

Desperate to please the sun and stop the weeping, the people of Earth made an attempt to rescue the dead daughter from the land of ghosts, but failed. When they returned, the sun began to weep even harder. To distract her, the people began to dance and play music until she finally became happy again.

Slowing down the sun

The Maori people of New Zealand tell a tale about a long-ago time when the days were shorter than they are now. The hero Maui often heard his brothers lamenting the lack of light during the day. He decided to solve the problem by taming the sun. Although his brothers were skeptical, they and their tribe helped Maui weave a net out of flax.

Maui and his brothers then set out to the east to find the sun's resting place. They covered the entry to the sun's cave with nets and smeared themselves with clay to protect against the sun's heat. When the sun emerged, it fought and struggled in the nets, but the brothers held firm. Maui began to beat the sun — some stories say he had an ax, others a club made of the jawbone of an ancestor — until the star was so weakened that it could no longer race across the sky. According to the legend, that is why the sun travels so slowly in the sky today.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus