Drought's Positive Effect: Smaller Gulf Dead Zone

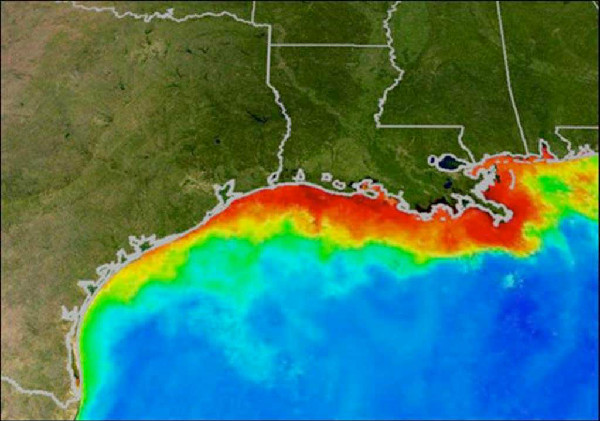

Though the parched conditions have wreaked havoc on natural habitat and agricultural crops, drought may have one upside, bringing the fourth smallest dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico since mapping of this annual oxygen-free zone began in 1985.

Scientists estimate the 2012 Gulf of Mexico dead zone spans an area of 2,889 square miles (7,482 square kilometers), or just larger than the state of Delaware.

"The smaller area was expected because of drought conditions and the fact that nutrient output into the Gulf this spring approached near the 80-year record low," Nancy Rabalais, executive director of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON), said in a statement. Rabalais led the survey cruise that measured the dead zone.

In fact, the last time the dead zone was this small was in 2000 when it measured 1,696 square miles, or 4,393 square km.

The number is also well below the 2011 dead zone, which reached 6,770 square miles (17,534 square km) as a result of floods that carried loads of nutrients into the water. Scientists recorded the smallest dead zone, at 15 square miles (39 square km), in 1988, while the largest zone occurred in 2002 and covered an 8,400-square-mile (21,756-square-km) swath.

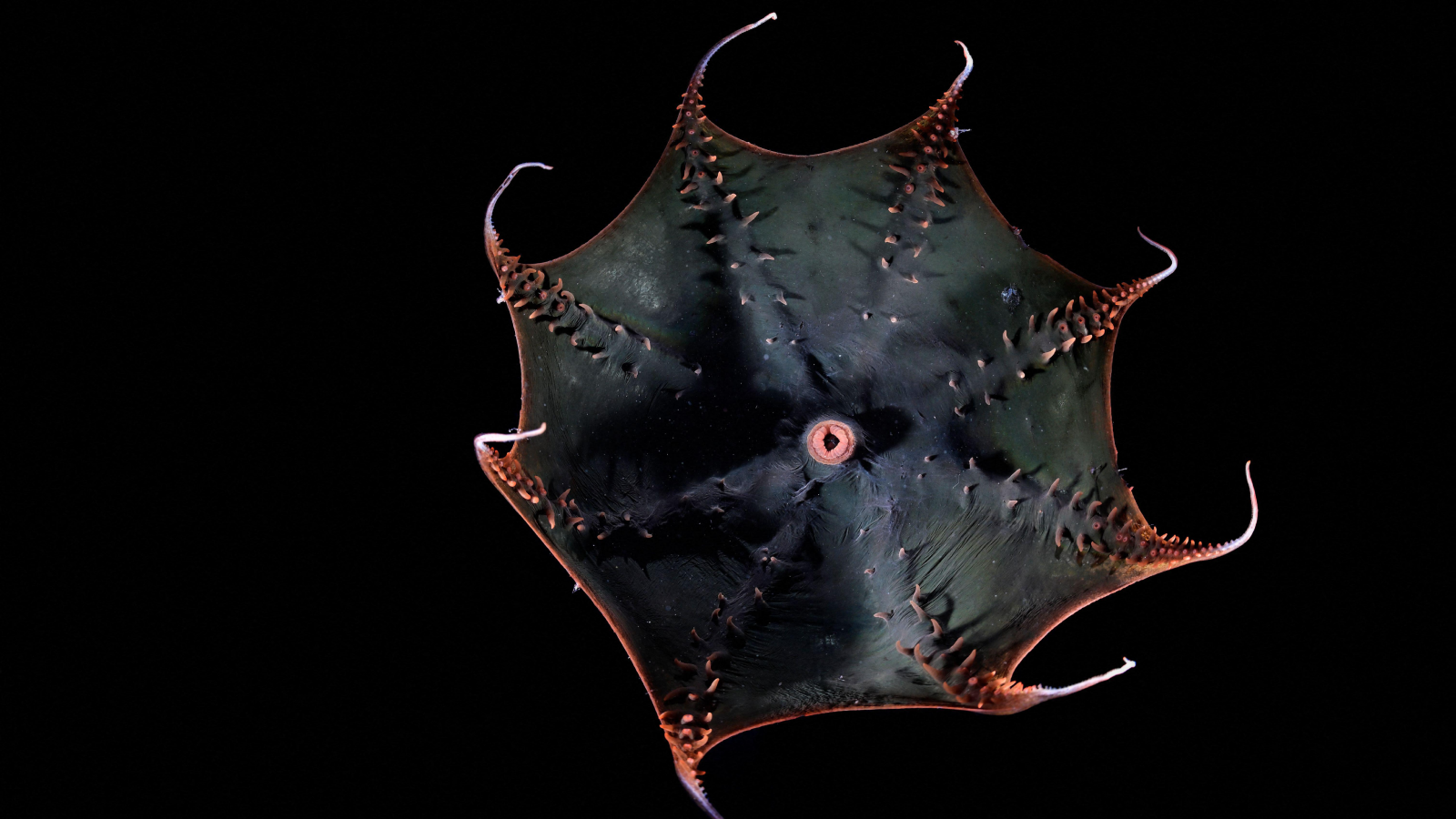

Estimates for this dead zone, which forms each summer off the coasts of Louisiana and Texas, are important because the loss of oxygen can be dire for the animals that live there; the dead zone also threatens commercial and recreational fishing in the Gulf.

The lack of oxygen results from nutrients, particularly nitrogen, that run off the land, from agricultural and other human activities, down the Mississippi River and into the Gulf of Mexico. These nutrients are food for algae, which grow as a result, before dying, sinking to the sea bottom and decomposing. It's this decomposition that sucks all the life-giving oxygen from the surrounding waters. [Mightiest Floods of the Mississippi River]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Two groups of researchers had forecast earlier this summer two very different potential sizes for this hypoxic zone, one on the small side and the other more in line with an average-size dead zone. The more conservative prediction, which involved researchers at the University of Michigan, took into account the nutrient-rich agricultural run-off from the Mississippi River watershed this spring. The "average" prediction accounted for leftovers from the prior year's nutrient pollution, called a carryover effect.

The new estimate for the zone's small size suggests this carryover effect on hypoxia was limited due to the drought (low flow) conditions, the researchers noted.

Researchers at Texas A&M plan a follow-up cruise in mid-August to provide an update on the dead-zone size.

The new research was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.