10,000 Microbes Cornered in Map of Human Body

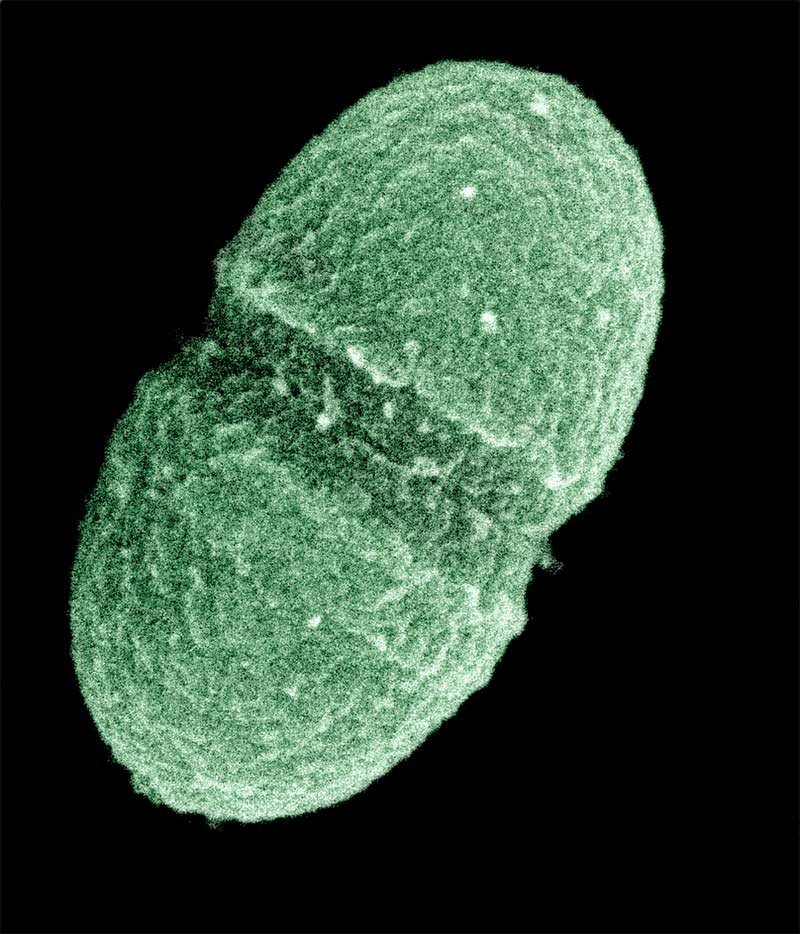

Regardless of whether you are more like Pig-Pen or Little Miss Tidy, all humans carry around several pounds of living bacteria and related ilk on and in their bodies. Most of these microscopic hitchhikers are harmless, and some actually are crucial for a healthy life; but others, should they gain an upper hand, can kill you.

Now, scientists have cataloged perhaps as much as 99 percent of the tiny critters that occupy nearly every inch of the human body inside and out.

This work, the culmination of a five-year effort called the Human Microbiome Project, involving hundreds of scientists and dozens of universities, appears in 16 scientific articles to be published tomorrow (June 14) in the journal Nature and in several journals in the Public Library of Science (PLoS).

You are not alone

Human microbes outnumber our own cells by a factor of 10 to 1. There are trillions. Most are bacteria, but also living in the mix are creatures you haven't seen since your high-school biology class: protozoa, archaea, bacteriophages, wormlike helminth parasites and yeasts.

Previously, scientists had isolated only a few hundred microbial species from humans. The Human Microbiome Project, which some researchers describe as a follow-up to the ambitious mapping of the human genome, has raised this count to more than 10,000 species. Scientists say this is likely between 81 percent and 99 percent of the true number of microbial species living on or in a healthy human.

The project's goal is to understand the location and concentration of the human microbiome and how these microbes are associated with human health and disease. For example, it is well known that the gut contains bacteria that make digestion possible. Far less is known, however, about how these bacteria can cause or alleviate various irritable bowel and digestion issues. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The nearly complete microbiome catalog, analogous to a map, will allow researchers to explore new interactions between microbes and the body's immune system.

"Knowing which microbes live in various ecological niches in healthy people allows us to better investigate what goes awry in diseases that are thought to have a microbial link," such as Crohn's disease, ulcers and obesity, said George Weinstock of Washington University in St. Louis, one of the project's principal investigators.

Full of surprises

The project already has yielded several surprise findings. For example, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston found fewer types of vaginal microbes in pregnant women compared with women not pregnant. This implies that the body somehow naturally reduces the microbial species diversity in the weeks and days approaching birth so that the newborn — who has developed in a sterile womb — can make a cleaner and healthier passage into the world. These results are published in the journal PLoS One. [10 Odd Facts About the Female Body]

Also published in PLoS One, researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have found evidence for entirely new groups of bacteria in the gut that span three major phyla (the category between kingdom and class) in the bacterial tree of life. Their work is based on DNA analysis of bacteria collected from healthy adults.

Meanwhile, researchers from Washington University in St. Louis, writing in the journal Nature as part of the Human Microbiome Project Consortium, found that all healthy people carry microbes known to cause illness. The most dangerous ones, such as anthrax, were not present; but many serious pathogens, such as virulent strains of E. coli and the ulcer-causing H. pylori, were common. Researchers said they hope to understand why and under what conditions these pathogens can turn deadly.

Other papers describe the impact of the microbiome on digestion, paving a path for treatments for the numerous diseases associated with irritable bowels, poor absorption of nutrients and food allergies.

Learn about your cargo

To catalog the human microbiome, researchers sampled 242 healthy U.S. volunteers and collected tissues from 15 body sites in men and 18 body sites in women. Sites included the mouth, nose, skin, lower intestine and three vaginal sites in women. The painstaking work was made possible through major advancements in recent years in DNA sequencing, which have made genetic analyses cheaper and faster.

The 14 papers in PLoS describing these and other microbiome findings are available freely at http://www.plosone.org.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus