Why 'Transgenic Stingray' Shoes Are Likely Fake

Want to buy a customizable sneaker made from transgenic stingray leather? You would be better off saving your $1,800 — scientists say the claims of Rayfish Footwear go beyond what is possible with modern genetic engineering.

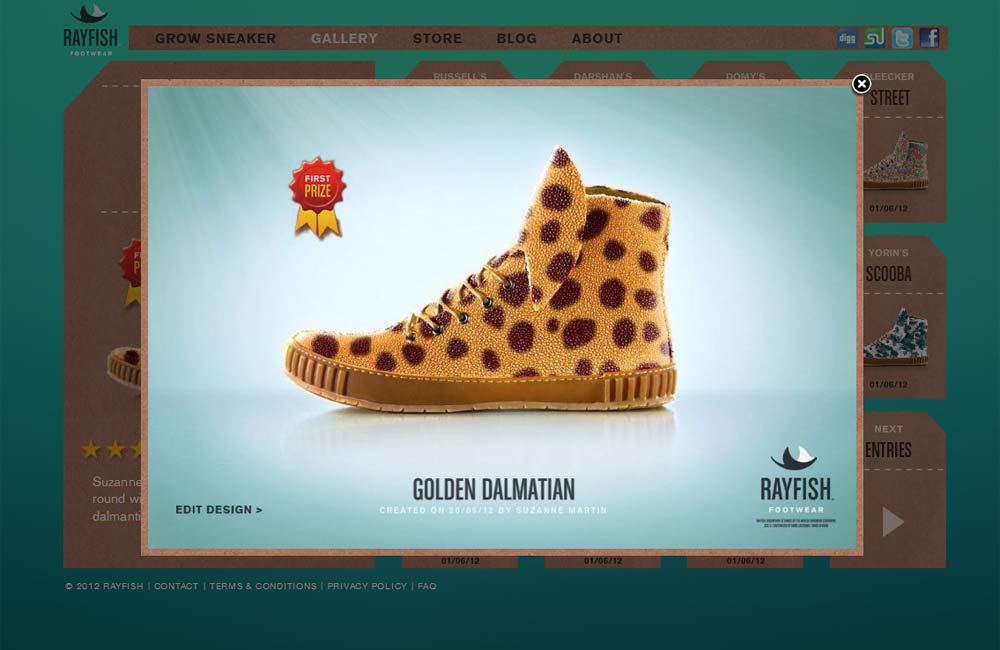

The Thailand-based Rayfish Footwear says it is able to genetically mix and match color patterns of different animals to grow transgenic stingrays with a look tailored to each shoe customer's wishes. But scientists say the idea of "bio-customized" stingray leather would require a huge leap in the ability to manipulate the many genes responsible for color patterns.

"To the best of my knowledge, there is no way to do what they claim both in terms of the colors, as many of those colors on their website have no way to be expressed in the skin, and the ability to completely control the pattern that they imply has not been achieved for any animal," said Randy Lewis, a biologist at Utah State University.

The transgenic stingray claim fails the reality check for at least two reasons, said Perry Hackett, a geneticist at the University of Minnesota. The first reason is that scientists still have difficulty inserting new genetic traits that rely upon many different genes working together, rather than just a single gene.

"The state of transgenic technology is that any gene from any organism can be moved into any other organism with a high probability that you can get what you want," Hackett told InnovationNewsDaily. "However, the fly in the ointment here is that if you're looking at things like patterns and the like, that's not due to a single gene. That's probably due to many genes acting in concert."

The second reason for doubting Rayfish Footwear's claim is that genes don't automatically express their given traits if plugged into a completely different animal. That means a transgenic stingray with the genes of a ladybug or a zebra won't automatically express the skin patterns of a ladybug or a zebra.

"If you wanted to introduce the same coloration that a German shepherd has into a stingray, it wouldn’t work because the tissues of a dog, a mammal, are different from the tissues of a stingray," Hackett explained. "So the regulation of genes is likely not to be the same at all, even assuming you could do something like that."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, genetic engineering has achieved some spectacular results. Scientists have inserted single genes to manipulate basic colors in some animals, or to make glowing varieties of dogs and cats. Lewis at Utah State University created transgenic goats, silkworms, E.coli bacteria and alfalfa capable of making spider silk proteins — work that inspired a Dutch artist to experiment with making "bulletproof" human skin. ['Bulletproof Human Skin' Made from Spider Silk]

Hackett pointed out that people in the U.S. can make the much safer investment of buying transgenic zebrafish marketed under the "Glofish" name — current varieties include red, green, yellow and purple. Such zebrafish also represent popular transgenic animals in research labs such as Hackett's.

Transgenic technology has gotten much better in the past decades, said Zhanjiang "John" Liu, a molecular biologist at Auburn University in Alabama. But he echoed the skepticism of his colleagues and said he would want to see the research backing up Rayfish Footwear's claim.

"If your stuff is real and your stuff can tolerate the test of time, get the stuff out there in the public and in front of [scientific] peers," Liu said.

Editor's Note: This story was edited to correct the second mention of Randy Lewis. He is a biologist at Utah State University, not the University of Utah.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus