Do Tarantulas Shoot Spidey Silk? Scientists Debate

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tarantulas, like all spiders, extrude silk from so-called spinnerets on their abdomens, and scientists recently found evidence suggesting the arachnids also shoot silk from their feet, Spider-Man style.

But these powers were fleeting, it seems, with new research showing tarantulas are not so like the famed superhero, after all. The tips of their eight legs don't shoot out Spidey silk.

"The history of science has plenty of examples which teach us that our present truths are provisional," Fernando Pérez-Miles, an entomologist at the University of the Republic in Uruguay, told LiveScience in an email. "But in my opinion the present evidence shows that tarantulas do not produce silk by their feet."

To hold on to vertical surfaces, spiders rely on molecular forces generated by thousands of microscopic hairs on their feet. Additionally, tiny foot claws allow them to cling to rough surfaces. In 2006, a study led by biologist Stanislav Gorb suggested that the zebra tarantula uses silk fibers — presumably produced by the nozzlelike spigots on their feet — to help them climb up a vertical glass wall.

"I have been studying tarantulas for more than 30 years and I have never seen any signal of silk production by tarantula feet," Pérez-Miles said.

Pérez-Miles and his colleagues repeated Gorb's experiment in 2009, with one small alteration: They sealed the tarantula's silk-spinning abdominal organs (the spinnerets) with paraffin. They didn't see any silk residues left on the glass. Though, they did find that tarantulas normally brush their hind legs against unsealed spinnerets as they climb, suggesting that the silk Gorb found was produced by the arachnids' spinnerets, not their feet. [See Photos of Tarantula Experiments]

But that wasn't the end of the story. Last year, biologist Claire Rind and her students at the University of Newcastle in the U.K. placed various tarantulas on horizontal glass slides, which they then raised to a vertical position and gently shook. The spiders' legs slipped slightly, but they regained their footing quickly, each time leaving behind microscopic silk threads — the team believes the arachnids only secrete silk from their feet as a lifeline to save themselves from falling, explaining why Pérez-Miles didn't see any silk in his experiments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

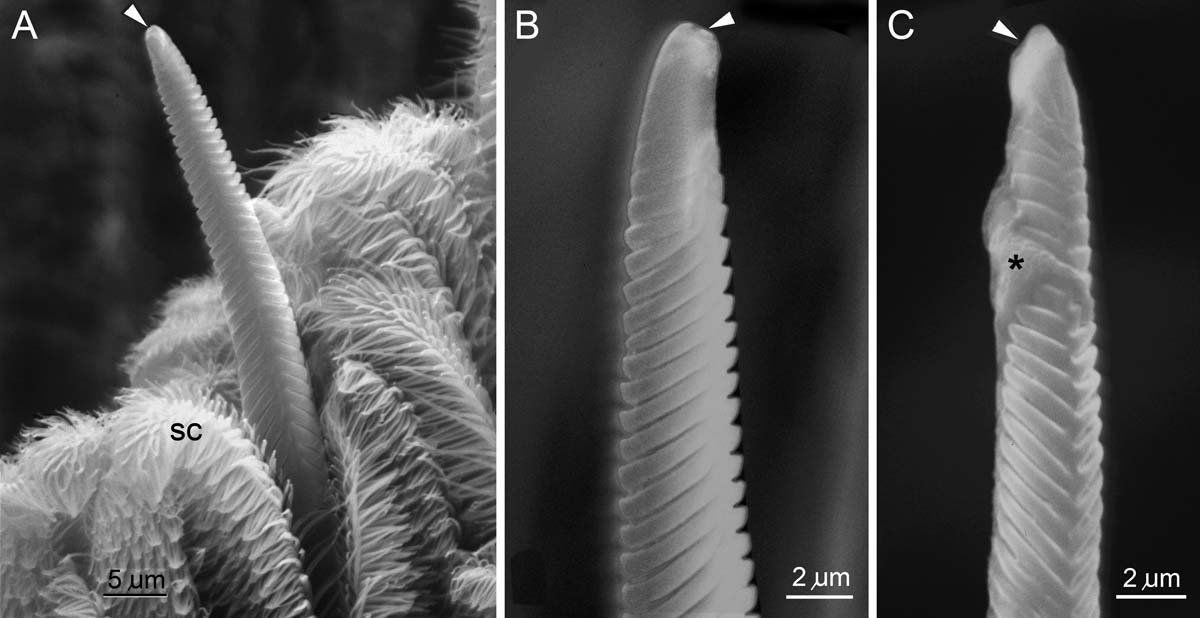

Next, to find the source of the foot silk, the researchers used an electron microscope to look at the feet of a dead tarantula. They found silk threads attached to ribbed, tapered structures that stuck out farther than the tiny foot hairs.

"But the microscopy was pretty poor," said arachnid specialist Rainer Foelix, author of "Biology of Spiders" (Oxford University Press, 2011). "There was such a low magnification of the silk threads that you couldn't tell them from a hole in the ground."

In a study published in April, Foelix and his colleagues compared the proposed foot spigots with spinneret spigots. They didn't look anything alike, but the foot structures strongly resembled the sensory hairs involved in taste and touch found elsewhere on the spiders. "Morphologically, it is very clear [the hairs] are sensory in nature," he said.

And in a study published in the May 15 issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology, Pérez-Miles repeated Rind's experiment, but again sealed the spider's spinnerets — he didn't find any silk thread on the glass.

The two studies contradict Rind's, but she still stands behind the findings and the tarantulas' Spider-Man-like ability. "So far no conclusive evidence has been given that the structures on the feet I described do not secrete silk, they just don't look like usual spigots," Rind told LiveScience in an email.

For Pérez-Miles the work isn't over: Though he and his team didn't see silk secretions, they did find some kind of residue on the glass. "The fluid footprints we found could be a secretion of chemoreceptors, but up to now we don't know the nature of this fluid," he said. He hopes to soon study the odd, spindly structures on the tarantulas' feet in more detail to fully unravel the mystery.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus