Forgery Artist's Long Trail of Fake Gifts Leads to Fame

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Matthew Leininger first became suspicious when the names of two pieces that had just been given to the Oklahoma City Art Museum also showed up as new donations at two other institutions.

It was August 2008. Leininger, registrar at the museum, took one of the works, an oil painting by a 19th-century Frenchman named Stanislas Lepine, and put it under an ultraviolet light. Parts glowed a bright, ominous white. A handheld magnifying loop confirmed the worst: telltale dots, the pixels of a digital copy.

Leininger then went to a third piece from the same donor, a centuries-old French academic drawing of a reclining nude.

"I remember to this day, I peeled back the lower left corner of the mat board that the supposed 17th- century drawing was attached to," he said. "Something that old should have been brittle or broken. It was stark white. I brought it to my nose; it smelled like stale coffee."

Under his own name

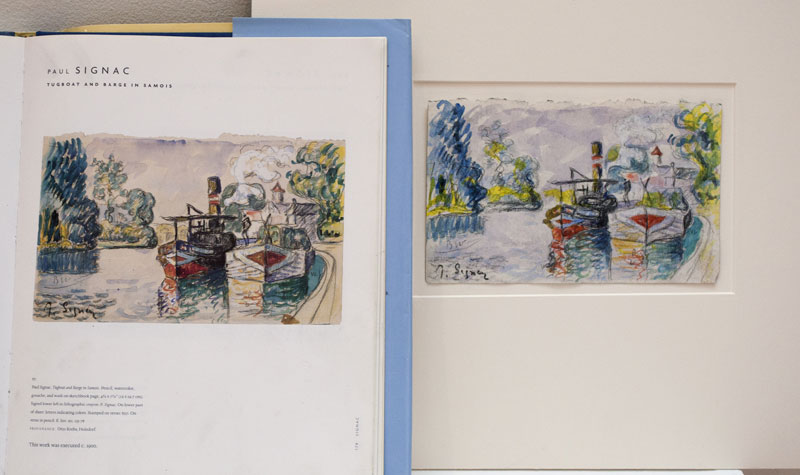

The donor, Mark Landis, later would admit to spilling instant coffee on his forgeries so they could better imitate aging works of art. He would describe working on them, assembly-line style, in his bedroom while watching TV, going over copies of the same picture with pens, paint or colored pencils. [How Mark Landis Forges Art]

Landis, who Leininger now suspects has presented more than 100 forged paintings to at least 50 institutions as gifts across 20 states, has never been charged with a crime. Instead he is being featured in an exhibit at the University of Cincinnati, featuring 40 of the pieces he donated and a brief autobiography he submitted at the university's request.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Leininger suspects the actual total is much higher.

"I think people don't want to come forward because they have been duped," Leininger said. "I believe he has gifted a lot more than what I have found."

But Landis doesn't offer much clarification. "That is more or less true," he said of Leininger's estimates, adding later that it is difficult to remember all the donations he's made. [Gallery of Landis' Forgeries]

Prolific and formerly elusive

After discovering the forgeries in 2008, Leininger began compiling information on Landis. Tracking Landis wasn't easy for a number of reasons; he moved around a lot, appearing at museums under aliases, including "Father Arthur Scott" a Jesuit priest. And he often gave to small and midsize institutions, which had fewer resources to check the authenticity of the artwork.

Two years after Leininger set about to curb Landis' practice, the prolific forger first caught the media's attention when The Art Newspaper ran a story in November 2010.

Aaron Cowan, the University of Cincinnati's director of galleries, read about the epidemic of forgered donations in the New York Times and contacted Leininger, who appeared in the story. The two decided to put together an exhibit on Landis. As work progressed, Cowan also found himself wanting more information.

"I had a number of questions that maybe I felt like had my suspicions, but they were still a little unclear to me, so I felt like the only way to resolve some these questions was to get in contact with Mr. Landis," Cowan said.

By this point, Leininger had received an email address for "James Brantley," one of Landis' aliases. He passed it on to Cowan, who began corresponding with Landis. Cowan said that eventually Landis began to send items for the exhibit; his first package included a pencil drawing of his mother and her biography.

Addicted

Landis also submitted his own biography. In it he states he was born March 10, 1955, in Norfolk, Va., to Navy Lt. Arthur and Jonita "Jo" Landis.

His his family traveled around the world while he was young, he writes. When his father was assigned to NATO, the family often visited many great European art museums. He remembers occupying himself by copying by hand pictures from their catalogs.

The story he tells about himself recounts some hardship: His father being passed over for a promotion, his own nervous breakdown and therapy that included arts and crafts; training at two art institutes; halting his training to go into business as an art dealer, then nearing bankruptcy. [10 Easy Paths to Self Destruction]

About this time, in 1985, Landis gave his first picture to a museum — something he said he did to honor his father, who by then had passed away, and to please his mother.

He said he passed the drawing off as the work of the American artist Maynard Dixon, whose depictions of the American West were fashionable at the time.

"I got a book with pictures of Indians in it, and I drew a picture of an Indian and I put his name on it," Landis told LiveScience in a phone interview. "I just walked in and everyone was just so nice. I'd never been treated so well before. It's a good feeling; I got used to it."

Landis now lives in his deceased mother's home in Laurel, Miss., where he keeps the phone bill and his email in his stepfather's name, James Brantley.

On the phone, Landis has a soft, high voice. He describes himself as "an unimpressive little bald guy." Photos of him published with other stories of his exploits convey an impish quality.

Landis said his donations were neither about money — he has not taken money or claimed tax benefits in return for his donations — nor about recognition.

"I am by no means a frustrated artist or anything like that. The simple explanation to all of that is I wanted mother to be proud of me, and she was," he said. "I got addicted to it because everyone was so nice."

"She kind of knew," he said of his mother, who died in 2010. "It's kind of a simple, everyday answer."

An unusual forger

"He is less in the mold of the majority of famous forgers than he is a quirky identity impostor," writes Noah Charney, an author and professor affiliated with the American University of Rome and Brown University, in text submitted for the Cincinnati exhibit. [9 Famous Art Forgers]

When asked about the effects on museums — who must now spend money to vet their donations and worry about the effects on their reputations — Landis said this had not crossed his mind.

"I just assumed that if later on they determined it wasn't genuine they would just throw it in the basement. It didn't occur to me that anyone would be upset or anything," he said.

Asked if he will stop making these donations, Landis seemed to hedge.

"Yeah, probably, I suppose. It will be rather difficult to [do] now," he said.

The exhibit "Faux Real"runs until May 20 in the Dorothy W. & C. Lawson Reed Jr. Gallery in the University of Cincinnati's College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus