Biblical Relic Dealer Acquitted in Forgery Trial, Sparking Controversy

An Israeli antiquities dealer accused of forging biblical and early Jewish relics has been acquitted of the charges, a verdict that is unlikely to dampen the controversy over whether the items, including a box supposedly containing the bones of Jesus' brother, are real.

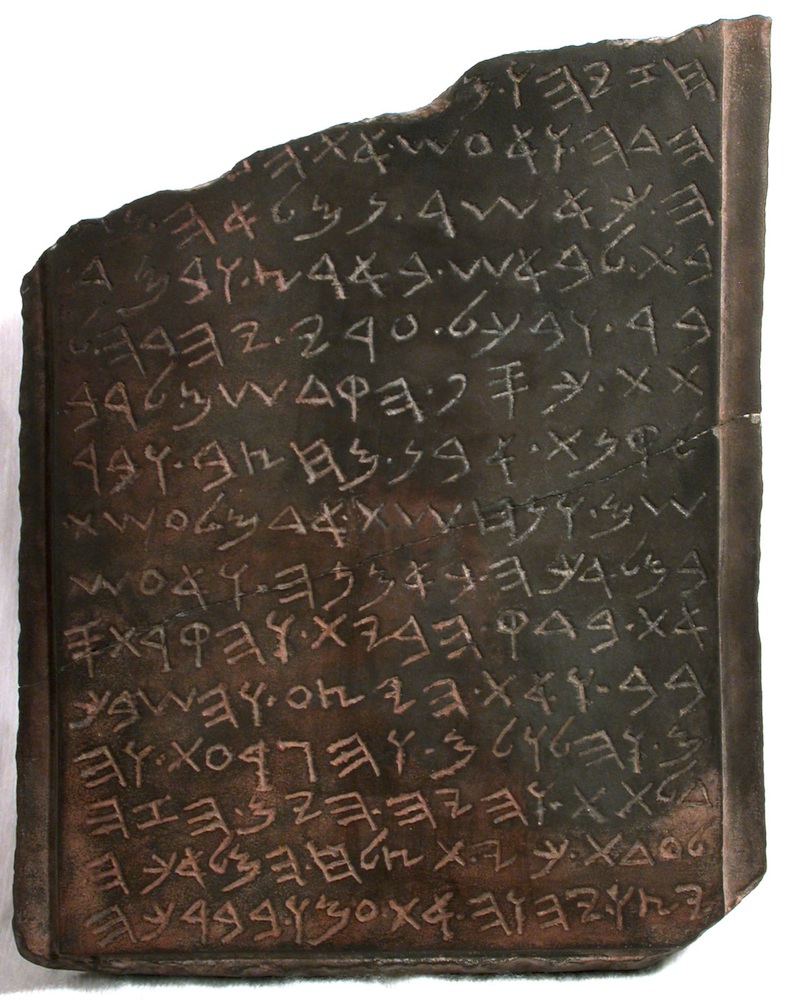

The Jerusalem District Court ruled today (March 14) that Oded Golan could not be proven guilty of forging inscriptions on a funerary box, or ossuary, and on a stone plaque supposedly from the First Temple, the main temple in ancient Jerusalem. According to the Hebrew Bible, the temple was constructed by King Solomon and was renovated in that late ninth century B.C. The plaque allegedly dates from these renovations. If real, the plaque would be the only surviving archaeological evidence of the temple.

Golan was found guilty of three lesser charges of possessing stolen property and violating antiquities law. But despite a judgment by a panel of experts convened by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) that the items are forgeries, the court concluded that there was not enough evidence to conclude that Golan had faked them.

The authenticity of the ossuary will "continue to be investigated in the archaeological and scientific arena, and time will tell," the court concluded, according to Reuters' reports.

"It appears that the judge did not rule on the question of whether the ossuary is authentic," said Nina Burleigh, a journalist and author of "Unholy Business: A True Tale of Faith, Greed and Forgery in the Holy Land" (Collins, 2008). "He explicitly states that he wasn't ruling on that."

Nonetheless, Burleigh said, the verdict will likely be a setback for the IAA and for authenticating archaeological finds in general. She cited an interview she conducted for her book with Tel Aviv University archaeologist Israel Finkelstein.

"He said, 'When there is an acquittal, which there probably will be, the market in these relics will be quiet for awhile,'" Burleigh told LiveScience. "'And then it won't be long before you see announcements internationally that Solomon's sandals have been found, and Mohammad's sword.'"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Questionable relics

The forgeries saga began in 2002, when Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum exhibited the ossuary, bearing the Hebrew inscription "James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." Golan claimed to have bought the ossuary from a dealer in the 1970s, only realizing its importance three decades later.

The relic was a media sensation, but archaeologists started raising alarm bells. The fraud unit of the Israel Police launched an investigation in conjunction with the IAA's Unit for the Prevention of Antiquities Robbery. According to the IAA, the investigation turned up evidence of a loose forgeries ring, in which Golan and others would alter antiquities with inscriptions to make them seem more valuable; for example, adding "brother of Jesus" to the ossuary belonging to "James son of Joseph." [Waiting for the Second Coming (Infographic)]

The case prompted the Israel Museum to evaluate some of its artifacts to re-check for evidence of forgery. The investigation turned up evidence that a carved ivory pomegranate, bought from an anonymous collector and once attributed to the First Temple, bears a forged modern inscription (though the pomegranate carving itself is ancient).

But for all the evidence of forgeries and the definitive fakes revealed in the trial, Israel Police and the IAA did not have the resources to "nail down the case," Burleigh said.

"The authentication of ancient objects is not the No. 1 priority," she said. "It's not even in the top 20 of what they're focused on. Israel is a challenged country."

On the stand, she added, the prosecution leaned heavily on the testimony of individual archaeologists. Defense lawyers were able to pick at the scientific evidence, making the authenticity of the ossuary and other objects seem more in doubt than it actually is.

"They quibbled over these tiny details, and the defense attorneys, who were very well-paid people, they were able to impeach almost every one of these very highly regarded scientists on the stand," Burleigh said.

Ongoing arguments

Though the number of scholars who believe that the ossuary and temple plaque are genuine has dwindled, there are a few interested parties who still argue vociferously for their authenticity. The lack of a guilty verdict seems likely to throw fuel on these debates.

Hershel Shanks, the editor of the magazine Biblical Archaeology Review, which published the original article introducing the ossuary, wrote an article blasting the IAA's conclusions on the magazine's website. [Album: Early Christian Inscriptions & Artifacts]

"Despite all that I have said, the inscriptions I have discussed will be considered forgeries in the public mind for at least a generation — never mind the acquittal of the defendants and the evidence of authenticity," Shanks wrote.

The IAA argues that good has come out of the Golan case. The field of archaeology took a hard look at publishing papers based on artifacts from the antiquities market, especially without detailed information on where the objects were found, the IAA wrote in a statement responding to the verdict on Wednesday (March 14). This, in turn, has made illicit excavations less profitable, reducing robbery at biblical sites, the agency said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.