Future 'Smart Homes' Will Watch and Remember Your Needs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

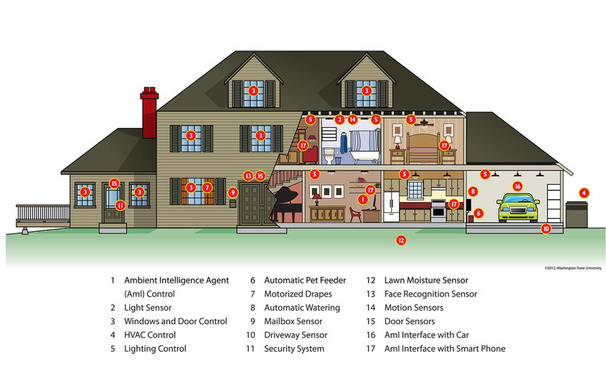

Technology lets people control the heat and lights of their home by programming a computer, but an engineer at Washington State University thinks the house should be able to handle those tasks, and much more, by itself someday. A "smart home" could not only set its own thermostat but learn its inhabitants' habits and preferences, and even catch the early signs of cognitive decline in older residents, according to the engineer's essay appearing today (March 29) in the journal Science.

Diane Cook, who runs 25 test smart homes throughout the Pacific Northwest, summarized in her paper what future high-tech houses could do and what researchers still have to figure out before everybody can live in one.

Cook's essay "hits it right on," said Sumi Helal, a computer scientist who researches smart homes at the University of Florida. Higher-tech homes in the future will need to learn over time, Helal said.

Cook, Helal (who knows Cook but was not involved with her essay) and other researchers are looking to give houses the ability to monitor and reason about what to do with the heat, air conditioning, lights, sprinklers and more, all without human input. Then people wouldn't have to deal with trying to program ever-more-complex thermostats or lighting systems.

"What we're interested in is giving computer software the ability to make some decisions about how to control your home," Cook said.

However, she is not interested in home conveniences simply for convenience's sake. Cook told InnovationNewsDaily that smart homes would be especially useful for older people or those with disabilities. Smart home systems could preserve an independent lifestyle for people who, because of age or illness, can't control or remember all the functions in their house. The home could remind them to take medications, or it could feed the cat for them and check the lights and windows after they've gone to bed.

Smart home systems also could monitor inhabitants' well-being. Cook's essay cites a 2010 finding that people older than 65 change their walking speed just before experiencing cognitive decline. A smart home could monitor elderly residents' gait and other movements to catch such subtle signs of ill health.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Several of Cook's test smart homes are in assisted-living apartments.

Helal says he, too, is motivated by the desire to help aging parents stay in the homes they love. Most people think of their own parents when they study this topic, he said. His mother is 79 years old and lives alone in Alexandria, Egypt. "I worry about her a lot," he said. He has found his research has many supporters, as people immediately think of relatives such smart homes would help. The close monitoring of a person by a smart home might seem unsettling, however. "Privacy concerns are and always will be an issue," Cook said.

She suggested that the next generation of homeowners may think differently about smart-home monitoring. If younger people, who are already accustomed to owning devices that track their data, got smart home technology for its other benefits, such as energy savings or a better security system, they might not mind having the system watch their health as they get older.

"Ideally we'd get this into people's homes now, so by the time they really need it for health purposes, it's already familiar to them," Cook said.

As it is, she said, the people who try her test homes usually feel better when they see the type of data the house collects and how most data are anonymized.

Cook's essay covers privacy issues well, Helal said. He would add that engineers will need to be careful to build safety features into smart technologies. They'll need to prevent heating or water from going awry, or the front door from opening in the middle of the night, letting in burglars or raccoons and skunks.

Cook and Helal said the chief remaining technological challenge before everyone lives in smart homes is that, for a computer, getting to know you is hard. In test houses, Cook found it's possible for a house to learn what is wanted by a single inhabitant with a regular routine. A large family with an irregular schedule, however, is more difficult for the system.

Detecting people in a house is "quite simple," but a smart system needs to make sense of what it detects without input from the people, Cook said. Just as Google and grocery stores track people's search terms and club card purchases to send them certain ads, a smart home will have to mine the data it gathers to figure out what to do.

Cook said researchers are working on getting a house's system to recognize sequences of events: "They're cooking right now, they're sleeping right now, or they're going to come home in 10 minutes so have the Jacuzzi ready right now."

Though researchers are still a long way from a house that can take raw data about its inhabitants and recognize activities or behaviors, the first smart homes may be here sooner than you think. "We'll have tens of millions of smart homes within three years because of the smart grid," Helal said. The next-generation power grid, which the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology is working to develop, would put "smart boxes" in people's homes that will sense the electricity usage in all of their outlets and reduce wasted power.

Though the goal of the smart technology in this case is energy savings, and not health or convenience monitoring, the idea is the same, Helal said. He thinks private companies will develop technologies to go along with the smart box. That tech may include health monitoring or other scrutiny and decision-making. "That is the beginning of it," Helal said.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily staff writer Francie Diep on Twitter @franciediep. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus