Something to Sweat: Earth Gets Steamier

It’s not the heat, but the humidity that will get you.

Not only is the planet getting hotter, but it's also becoming more humid, as a result of human-induced global warming, a new study finds. A steamier Earth could mean more extreme precipitation and sweatier days for humans.

Scientists had previously observed increases in humidity over certain regions and in some global data over the past few decades, and while climate models predicted the increase (because warmer air can hold more moisture), it had not yet been attributed to human-induced global warming.

Models vs. observations

So researchers at the University of East Anglia in England and the U.K. Met Office compiled a global data set of humidity records and compared them to models run over the same period, focusing on three types of climate influences: only anthropogenic (or man-made), natural and a combination of the two. When the researchers compared the observational records to the model results (detailed in the Oct. 11 issue of the journal Nature), they found a clear anthropogenic influence.

"It matches best when you account for both the natural and anthropogenic," said Nathan Gillett of the University of East Anglia, "but it's the anthropogenic [model result] that has most of the trend in it."

The humidity increase isn't the same type of humidity featured on the daily weather forecast. The latter quantity, called relative humidity, tells you how much water is in the air as a fraction of the water that the air can actually hold at its current temperature. (So air that is at 100 percent humidity is holding all the water that it can, but if it's temperature increased and the amount of water vapor stayed the same, the relative humidity would decrease).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specific humidity, on the other hand, is a ratio of the amount of water vapor to the amount of air, and so tells you how much water vapor is in the air, regardless of how much water vapor the air is capable of holding. This was the quantity measured by the study, so the increase in humidity indicates that the actual amount of water vapor in the air is increasing.

Greenhouse gas

The increase in water vapor brought about by rising temperatures can actually cause a further increase in global temperatures, because water vapor is also a greenhouse gas.

"This increase in water vapor is a feedback on global warming," Gillett told LiveScience.

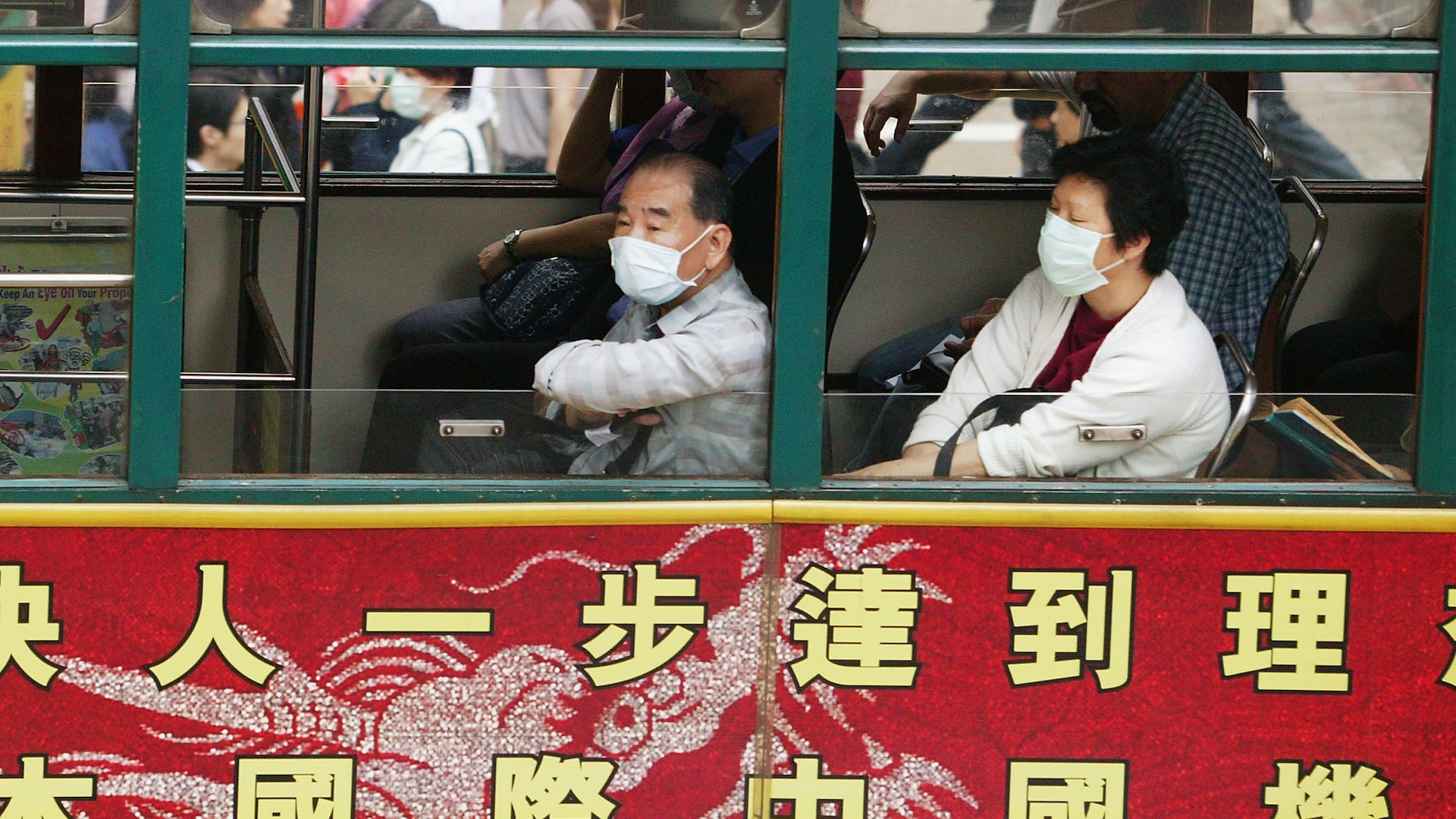

With the increase in humidity comes more risk of heat stress to people who live in places where humidity is increasing the most, especially in the tropics. The increasing humidity will also likely bring more precipitation to the tropics, another prediction of climate models.

The team's models predicted increases in humidity in the same regions that others' climate models have predicted increased precipitation, and that could explain why those climate models have predicted where more precipitation will occur, but not how much it will increase.

"We find that the model does a good job of predicting the humidity change," Gillett said. "The fact that they're doing OK with the humidity might help us start to pin down where they're going wrong with rainfall."

- Why is Humidity So Uncomfortable?

- Top 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- Timeline: The Frightening Future of Earth

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.