Citizen Scientists Discover Cosmic Bubbles in Milky Way Galaxy

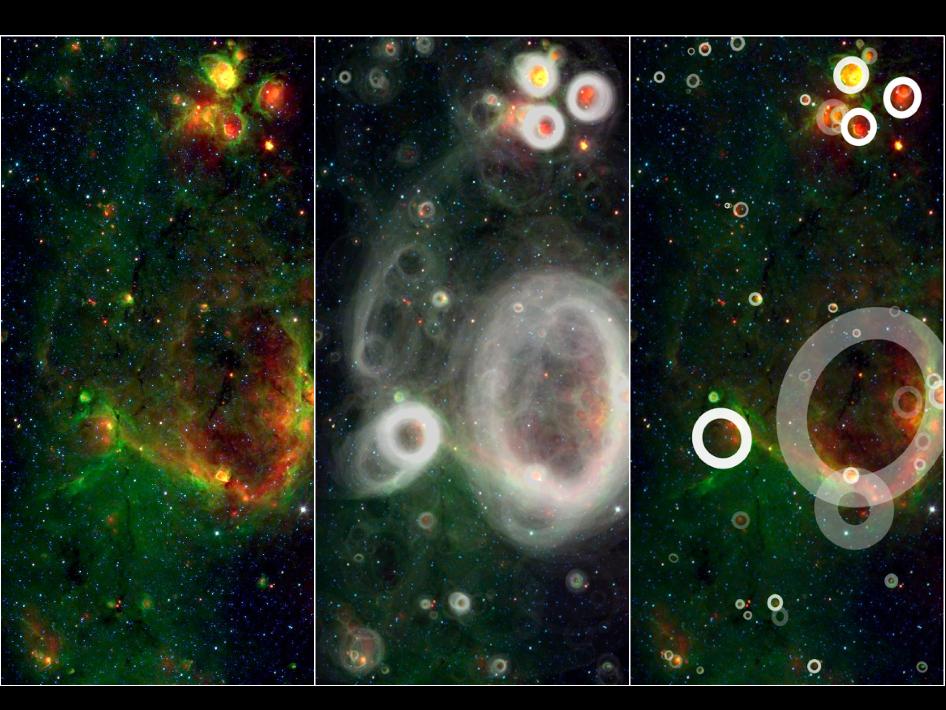

More than 5,000 space bubbles have been discovered in the disk of our Milky Way galaxy by a team of part-time citizen scientists.

These bubbles are blown by young, hot stars into the surrounding gas and dust, and indicate areas of brand-new star formation, scientists say.

"These findings make us suspect that the Milky Way is a much more active star-forming galaxy than previously thought," Eli Bressert, an astrophysics doctoral student at the European Southern Observatory, said in a statement. "The Milky Way's disk is like champagne with bubbles all over the place."

About 35,000 volunteers sifted through data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope on the online Milky Way Project to make the discoveries. These citizen scientists have found about 10 times more bubbles than previous surveys.

In this case, human eyes are very good at spotting what computer programs often miss. The volunteers were able to identify partially broken rings and overlapping bubbles that would have confused algorithms. To make sure the volunteers identify likely bubbles, the program requires each candidate bubble to be flagged by five participants before it's added to the catalog.

"The Milky Way Project is an attempt to take the vast and beautiful data from Spitzer and make extracting the information a fun, online, public endeavor," said principal investigator of the Milky Way Project Robert Simpson, a postdoctoral researcher in astronomy at Oxford University in England.

Astronomers hope to use this collection of cosmic bubbles to study star formation in the galaxy. The results are already turning up some surprises, such as the fact that bubbles seem to be less common on either side of the galactic center.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We would expect star formation to be peaking in the galactic center because that's where most of the dense gas is," Bressert said. "This project is bringing us way more questions than answers."

The study is detailed in a paper submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus