Behemoth Antarctic Algae Bloom Seen from Space

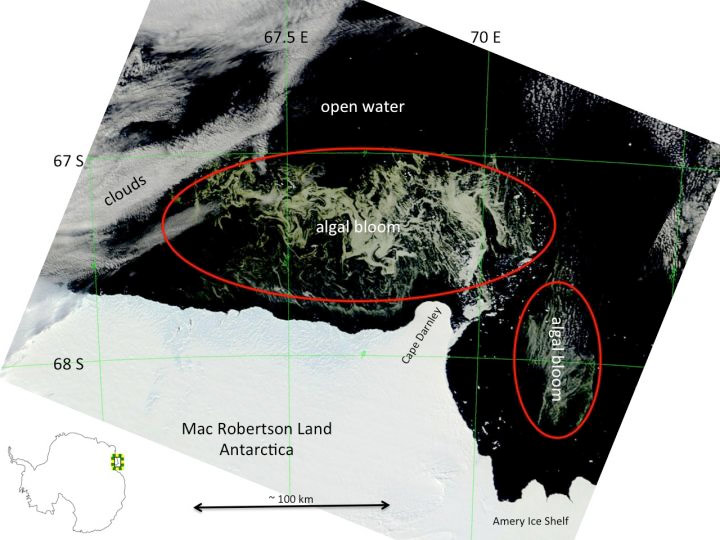

An enormous algae bloom off the coast of Antarctica is so huge and colorful that it can easily be seen from space.

A stunning photo of the monster algae bloom was released March 4 by the Australian Antarctic Division.

The bloom hugs the coast of eastern Antarctica and has been present since mid-February. Marine glaciologist Jan Lieser of the Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems Cooperative Research Center (ACE) in Australia said in a statement that the event is remarkable.

"We know that algal blooms are a natural occurrence down south —it's just a part of the Southern Ocean," Lieser told Australian website The Conversation. "But I've never seen one on this scale before. It's been going on for about 15 days now, so it's maybe about two-thirds or three-fourths of the way through the cycle.”

The bloom stretches about 124 miles (200 kilometers) east to west and 62 miles (100 km) north to south. The image of this gigantic bloom was taken by the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instrument aboard NASA's Earth-orbiting Terra satellite; together with the Aqua satellite, Terra views Earth's entire surface every one to two days, acquiring data in several wavelengths of light.

On Feb. 27, MODIS spotted another Antarctic phytoplankton bloom, this one off the coast of the Princess Astrid Coast.

Algae blooms like these are triggered when a combination of sunlight and nutrients create fertile conditions. In the Southern Ocean, iron is the limiting nutrient, according to ACE. When iron concentrations are high enough, algae blooms follow.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This particular bloom is thought to be made up of phaeocystis, a single-celled algae well-known in polar areas. Algae also live on land in the Antarctic, sometimes in concentrations high enough to color snow banks red, green and orange. Australian research vessel Aurora Australis is venturing near the Antarctic bloom so scientists can collect samples of the algae.

Algae is the base of the ocean food chain, and in the Southern Ocean, as is the case elsewhere, they take up the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide as they photosynthesize and grow. But massive blooms occasionally cause trouble. Some species of algae produce neurotoxins that are deadly. Humans who eat shellfish that have fed on Alexandrium catanella, the algae responsible for "red tides," can die of paralytic shellfish poisoning.

Some researchers even suspect that algae poisoning contributed to all five of Earth's great mass extinctions, which killed off between half and 90 percent of all animal species when they occurred. According to this controversial theory, there were increased levels of algae in at least four of the five mass extinctions in Earth's history. A cataclysmic event such as a volcanic eruption or asteroid impact could have stressed the algae, causing them to release more toxins and further harm the ecosystem.

You can follow LiveSciencesenior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.