'Smart Clothing' Could Become New Wearable Gadgets

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Today's ordinary clothing has the untapped power to become tomorrow's wearable electronics. A Canadian lab has tested special fibers that can help make soft, flexible touch screens and batteries woven directly into the fabrics of modern life.

Turning rigid electronic parts into stretchy, smart clothing material has not proven easy. But early ideas have already hinted at practical uses beyond just wearing glowing "Tron" jumpsuits as fashion accessories. People may swipe a finger across a car's upholstery to turn down the heat or brush at their coat sleeves to adjust the volume of a connected music player ? experiences that seamlessly blend "hard" gadget functions with "soft" objects.

"We don't want humans to be aware of what they are wearing," said Maksim Skorobogatiy, a physicist at Ecole Polytechnique de Montreal in Canada. "It has to be self-contained piece that can charge itself, store energy and perform useful functions. Otherwise, it's an extra burden that nobody needs in our lives."

That philosophy has driven Skorobogatiy to assemble a diverse team of researchers focused on making the soft versions of electronic gadget parts, including multitouch screens, batteries and even microchip transistors. Those technologies could lead to smart clothing that monitors a person's health signs, or even acts as a wearable computer.

"The problem with most of the soft electronics ? the few examples that exist nowadays ? is that people mostly just put chips or widgets onto textiles and try to enable interesting textile functions," Skorobogatiy told InnovationNewsDaily. "Most of the electronics are not designed for soft interfaces."

Some labs have tried embedding tiny nanoparticles inside ordinary cotton thread so that they can conduct electricity. But they must wrestle with problems in making the material last a long time, as well as needing to use chemicals to bind the nanoparticles to the cotton.

By contrast, Skorobogatiy's lab turned to the manufacturing process used to create the optical fibers that carry TV and Internet signals. The technique allowed the Canadian team to make new polymer-based fibers based on melting the preformed material to pull out a long, thin fiber shape. Such fibers can conduct electric signals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers wove the fibers into an experimental touchpad that showed off partial multitouch capability similar to what smartphones or tablets possess. That work appeared in the January issue of the journal Smart Materials and Structures.

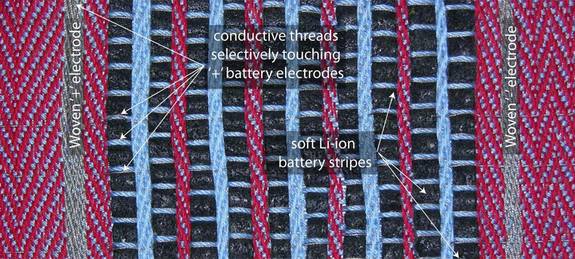

Next, they made flat sheets of batteries by combining typical lithium battery materials with thermoplastic binder material. Skorobogatiy's lab cut the battery sheets into thin strips and wove the strips into typical clothing textiles ? an achievement detailed in the January issue of the Journal of the Electrochemical Society.

The technology of smart clothing may seem imminent, but psychological barriers remain because textile manufacturers are hesitant to work with completely new fibers. The Canadian researchers have begun working on toppling such barriers by providing fibers for designers to try out.

One big challenge remains ? creating the soft textile version of the transistors at the heart of all modern devices. If Skorobogatiy's lab can pull off that trick, they could enable extraordinary pieces of smart clothing that act like gadgets but easily fit in with ordinary wardrobes.

"We're moving toward a self-contained textile battery, electronics and sensors ? all made with textile thread," Skorobogatiy said. "At this point, we're only missing the electronics."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus